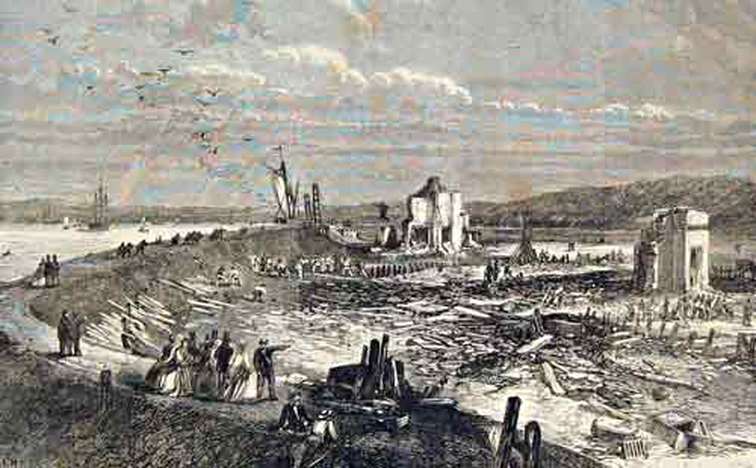

1864 Scene of explosion Gunpowder Magazine from Erith (Crossness area)

A picture from the London Illustrated News, depicting the aftermath of the gunpowder explosion in 1864

TERRIFIC GUNPOWDER EXPLOSION AT ERITH. (Home News.)

Early on Saturday morning, October 1, two gunpowder magazines, situated on the southern bank of the Thames, between Woolwich and Erith, exploded with terrific violence, killing and wounding several persons, and carrying consternation and alarm among the inhabitants for miles round. Although the scene of the catastrophe is distant about 15 miles from Charing cross, the shock was felt more or less throughout the whole metropolis, and even at places 40 and 50 miles from the spot as far as Newmarket and Cambridge on the one hand, and Windsor and Guildford on the other.

The explosion occurred in a gunpowder depot belonging to Messrs. John Hall, and Sons, and almost simultaneously in a magazine of smaller size used by the Low Wood Gunpowder Company, formerly known as the firm of Messrs. Daye and Barker, both of them located in the Plumstead marshes on the margin of the Thames, two miles west of Erith, and about an equal

distance from the village of Belvedere, on the North Kent Rail- way. Here, on about 20 acres of ground, separated, for obvious reasons, from the rest of the neighbouring houses, but in three cottages in the immediate vicinity of the scene of their daily labour, lived a few working men with their families. One was George feayner, who acted as storekeeper in the depot of Messrs. Hall, and who was a married man with a family, and another, named Walter Silver, also married, acted in a similar capacity under the Low Wood Gunpowder Company.

Each of these had a cottage to himself about 100 or 200 yards from the magazines, and the rest, who were men employed in the larger depot, occupied a cottage in common. The Messrs. Hall have been engaged in the business of fabricating gunpowder for more than 50 years, and have executed large contracts from time to time both for our own and many foreign Governments. They have a large factory in the neighbourhood of Faversham, in Kent, occupying about

200 acres of ground, part of the works at which were erected in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

There the work of manufacturing and packing gunpowder is conducted by a body of trained artisans, with all the safeguards and precautions suggested by experience ; and within the last few years the proprietors have purchased a large tract of adjacent lana in order the more completely to seclude their operations from the habitations of men. Their magazine at

Belvedere was a substantial building, about 50 feet square, and consisting of two floors, and around it were l8 acres of land, with a view to isolate the building. For miles at that part of the river there is an embankment, which protects the low-lying marshes from inundation. Both their depot and that of the Low Wood Company stood close behind the embankment. The quantity of gunpowder stored in Messrs. Hall's magazine at the time of the explosion, and in two of

their barges which lay off the jetty, is estimated by themselves at about 750 barrels in the depot, and perhaps 200more in the barges, each barrel containing 1001b. The quantity in the magazine of the Low Wood Company was only about 90001b. Their magazine, which was about 40 feet long by 30 feet in width, and consisted of two floors, stood at a distance of about 60 or 70 yards from that of Messrs. Hall. Both Messrs. Hall's magazine and that of the Low Wood Company

had a wooden jetty projecting into the river for the loading and unloading of gunpowder.

It should be understood that these were places used entirely for the storage of gunpowder, and in no sense for its manufacture. Between their mills at Faversham and the magazine at Belvedere, a distance of about 30 miles, the gun powder is conveyed in sailing barges, each navigated usually by a couple of men, and two of these, as has been stated, were moored alongside the jetty on the morning of the explosion, discharging cargo. The gunpowder, carefully packed in barrels, is borne on trucks with copper wheels along wooden rails, in order

to preclude the possibility of a spark from friction and the operation is conducted with other precautions, such as the wearing of list slippers by the men engaged in it. Immediately after the calamity an immense pillar of smoke rose from the spot high into the air-thick, black, and palpable, with huge spreading top-and about a quarter of an hour elapsed before it died away. As soon as it was sup- posed to be safe to do so, people from Erith and Belvedere

proceded to the spot and ventured to explore the ruins in search of anyone that might be living. Of the magazines themselves not a single stone remained upon another, the very foundations being torn up, and the site of that of Messrs. Hall was marked by huge fissures and chasms in the earth, immense lumps of which had been scooped out and hurled about the adjacent fields. The barges, with the jetty, had been split into fragments and blown into the air, and an enormous

rent had been made in the embankment itself, ex- posing miles of country to the peril of inundation. Of the cottage of the foreman, Rayner, nothing was lett standing but a bit of brick wall and a doorway. The lifeless bodies of the unfortunate man himself and of his son were found close by, and his wife and a child were dug out of the ruins alive, but hurt in various ways. A child, niece of Silver, the fore- man at the other depot, was killed, while he himself escaped with some slight injuries. His wife, fortunately, had gone on a visit to some friends at Maidstone a few days before and had not returned. The cottage in which they lived is simply a ruin, and the whole immediate neighbourhood was covered with the debris of the fallen buildings. Those of the sufferers, nine in number, who were still living, were conveyed with as much care and speed as possible to Guy's Hospital, where some of them have since died.

No light has as yet been thrown upon the cause of the catastrophe, and there is no probability that the origin of the explosion will never be known. Everything within its reach was annihilated. Man and matter perished together, shivered into a thousand fragments and whirled into space. People know there used to be a magazine in the Erith marshes, but there is now only a yawning crater there. The very ruins are lost. A visitor to the spot went to look for a cottage which he

remembered ; it had been " swept entirely away, as with a broom." Every witness whose evidence could have thrown light on the catastrophe has been hurried out of the world by that tremendous thunder- clap. Those immediately concerned can hardly be returned as killed-they are "missing"-that is to say, their very bodies have disappeared. The nearest approach to a piece of evidence is in a strange unearthly kind of story : Three men were on the river in a lighter near

the Belvedere jetty, between 6 and 7 o'clock on the morning of the disaster.

They had observed the barges, and " men walking on them," but nothing more.

Presently they found themselves enveloped in a great flood of light, and violently thrown down. One of them was forced overboard into the water, where a man came to help him, but that man had his right whisker blown off, and has not been heard of since. Nobody saw how, when, or where the explosion began.

The sufferers by the explosion are said to number 17. Of these 10 are dead, but five

of them, including the bargemen, have been blown away, and are therefore reckoned as missing. Seven of the sufferers are at Guy's Hospital ; and these, with one exception, are doing well.

The damage done to property by the explosion extends to a radius of 20 miles. The effect upon domesticated animals is said to have been very remarkable. Thousands of pets succumbed with fright, the mortality to canaries being very great.

In the immediate-neighbourhood at the time of the explosion, they in every in stance dropped from their perches, and in very numerous cases expired.

Parrots, also, dropped into the bottom of their cages, refusing to, move for a quarter of an hour; whilst dogs, cats, and other animals manifested symptoms of the * greatest alarm. In the large district of grazing' marshes, extending from Rainham to Purfleet, the sheep, cows, and i horses seemed at first petrified with alarm, , and then started off with a reckless wilderness which did not entirely subside for some hours. The same effect in a less degree prevailed with the cattle in the more distant agricultural district round Eltham, as far as Bromley, including the deer in Greenwich, Charlton, and private parks. The scientific instruments at the Royal Observatory were much disturbed, and showed that there were 60 undulations in the two seconds the vibrations lasted.

Early on Saturday morning, October 1, two gunpowder magazines, situated on the southern bank of the Thames, between Woolwich and Erith, exploded with terrific violence, killing and wounding several persons, and carrying consternation and alarm among the inhabitants for miles round. Although the scene of the catastrophe is distant about 15 miles from Charing cross, the shock was felt more or less throughout the whole metropolis, and even at places 40 and 50 miles from the spot as far as Newmarket and Cambridge on the one hand, and Windsor and Guildford on the other.

The explosion occurred in a gunpowder depot belonging to Messrs. John Hall, and Sons, and almost simultaneously in a magazine of smaller size used by the Low Wood Gunpowder Company, formerly known as the firm of Messrs. Daye and Barker, both of them located in the Plumstead marshes on the margin of the Thames, two miles west of Erith, and about an equal

distance from the village of Belvedere, on the North Kent Rail- way. Here, on about 20 acres of ground, separated, for obvious reasons, from the rest of the neighbouring houses, but in three cottages in the immediate vicinity of the scene of their daily labour, lived a few working men with their families. One was George feayner, who acted as storekeeper in the depot of Messrs. Hall, and who was a married man with a family, and another, named Walter Silver, also married, acted in a similar capacity under the Low Wood Gunpowder Company.

Each of these had a cottage to himself about 100 or 200 yards from the magazines, and the rest, who were men employed in the larger depot, occupied a cottage in common. The Messrs. Hall have been engaged in the business of fabricating gunpowder for more than 50 years, and have executed large contracts from time to time both for our own and many foreign Governments. They have a large factory in the neighbourhood of Faversham, in Kent, occupying about

200 acres of ground, part of the works at which were erected in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

There the work of manufacturing and packing gunpowder is conducted by a body of trained artisans, with all the safeguards and precautions suggested by experience ; and within the last few years the proprietors have purchased a large tract of adjacent lana in order the more completely to seclude their operations from the habitations of men. Their magazine at

Belvedere was a substantial building, about 50 feet square, and consisting of two floors, and around it were l8 acres of land, with a view to isolate the building. For miles at that part of the river there is an embankment, which protects the low-lying marshes from inundation. Both their depot and that of the Low Wood Company stood close behind the embankment. The quantity of gunpowder stored in Messrs. Hall's magazine at the time of the explosion, and in two of

their barges which lay off the jetty, is estimated by themselves at about 750 barrels in the depot, and perhaps 200more in the barges, each barrel containing 1001b. The quantity in the magazine of the Low Wood Company was only about 90001b. Their magazine, which was about 40 feet long by 30 feet in width, and consisted of two floors, stood at a distance of about 60 or 70 yards from that of Messrs. Hall. Both Messrs. Hall's magazine and that of the Low Wood Company

had a wooden jetty projecting into the river for the loading and unloading of gunpowder.

It should be understood that these were places used entirely for the storage of gunpowder, and in no sense for its manufacture. Between their mills at Faversham and the magazine at Belvedere, a distance of about 30 miles, the gun powder is conveyed in sailing barges, each navigated usually by a couple of men, and two of these, as has been stated, were moored alongside the jetty on the morning of the explosion, discharging cargo. The gunpowder, carefully packed in barrels, is borne on trucks with copper wheels along wooden rails, in order

to preclude the possibility of a spark from friction and the operation is conducted with other precautions, such as the wearing of list slippers by the men engaged in it. Immediately after the calamity an immense pillar of smoke rose from the spot high into the air-thick, black, and palpable, with huge spreading top-and about a quarter of an hour elapsed before it died away. As soon as it was sup- posed to be safe to do so, people from Erith and Belvedere

proceded to the spot and ventured to explore the ruins in search of anyone that might be living. Of the magazines themselves not a single stone remained upon another, the very foundations being torn up, and the site of that of Messrs. Hall was marked by huge fissures and chasms in the earth, immense lumps of which had been scooped out and hurled about the adjacent fields. The barges, with the jetty, had been split into fragments and blown into the air, and an enormous

rent had been made in the embankment itself, ex- posing miles of country to the peril of inundation. Of the cottage of the foreman, Rayner, nothing was lett standing but a bit of brick wall and a doorway. The lifeless bodies of the unfortunate man himself and of his son were found close by, and his wife and a child were dug out of the ruins alive, but hurt in various ways. A child, niece of Silver, the fore- man at the other depot, was killed, while he himself escaped with some slight injuries. His wife, fortunately, had gone on a visit to some friends at Maidstone a few days before and had not returned. The cottage in which they lived is simply a ruin, and the whole immediate neighbourhood was covered with the debris of the fallen buildings. Those of the sufferers, nine in number, who were still living, were conveyed with as much care and speed as possible to Guy's Hospital, where some of them have since died.

No light has as yet been thrown upon the cause of the catastrophe, and there is no probability that the origin of the explosion will never be known. Everything within its reach was annihilated. Man and matter perished together, shivered into a thousand fragments and whirled into space. People know there used to be a magazine in the Erith marshes, but there is now only a yawning crater there. The very ruins are lost. A visitor to the spot went to look for a cottage which he

remembered ; it had been " swept entirely away, as with a broom." Every witness whose evidence could have thrown light on the catastrophe has been hurried out of the world by that tremendous thunder- clap. Those immediately concerned can hardly be returned as killed-they are "missing"-that is to say, their very bodies have disappeared. The nearest approach to a piece of evidence is in a strange unearthly kind of story : Three men were on the river in a lighter near

the Belvedere jetty, between 6 and 7 o'clock on the morning of the disaster.

They had observed the barges, and " men walking on them," but nothing more.

Presently they found themselves enveloped in a great flood of light, and violently thrown down. One of them was forced overboard into the water, where a man came to help him, but that man had his right whisker blown off, and has not been heard of since. Nobody saw how, when, or where the explosion began.

The sufferers by the explosion are said to number 17. Of these 10 are dead, but five

of them, including the bargemen, have been blown away, and are therefore reckoned as missing. Seven of the sufferers are at Guy's Hospital ; and these, with one exception, are doing well.

The damage done to property by the explosion extends to a radius of 20 miles. The effect upon domesticated animals is said to have been very remarkable. Thousands of pets succumbed with fright, the mortality to canaries being very great.

In the immediate-neighbourhood at the time of the explosion, they in every in stance dropped from their perches, and in very numerous cases expired.

Parrots, also, dropped into the bottom of their cages, refusing to, move for a quarter of an hour; whilst dogs, cats, and other animals manifested symptoms of the * greatest alarm. In the large district of grazing' marshes, extending from Rainham to Purfleet, the sheep, cows, and i horses seemed at first petrified with alarm, , and then started off with a reckless wilderness which did not entirely subside for some hours. The same effect in a less degree prevailed with the cattle in the more distant agricultural district round Eltham, as far as Bromley, including the deer in Greenwich, Charlton, and private parks. The scientific instruments at the Royal Observatory were much disturbed, and showed that there were 60 undulations in the two seconds the vibrations lasted.

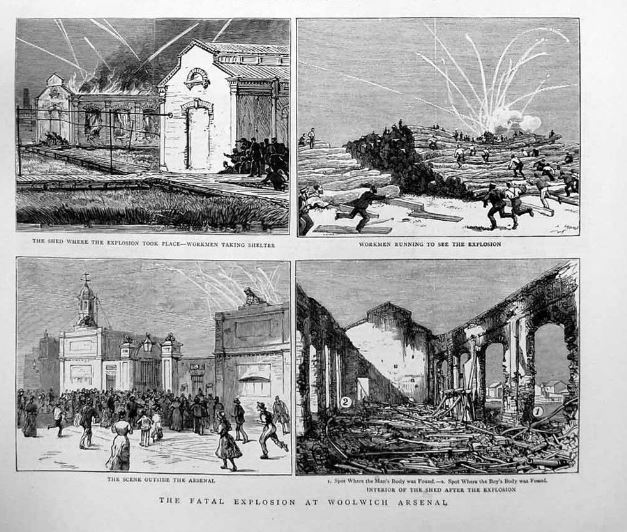

1883 Woolwich Arsenal explosion

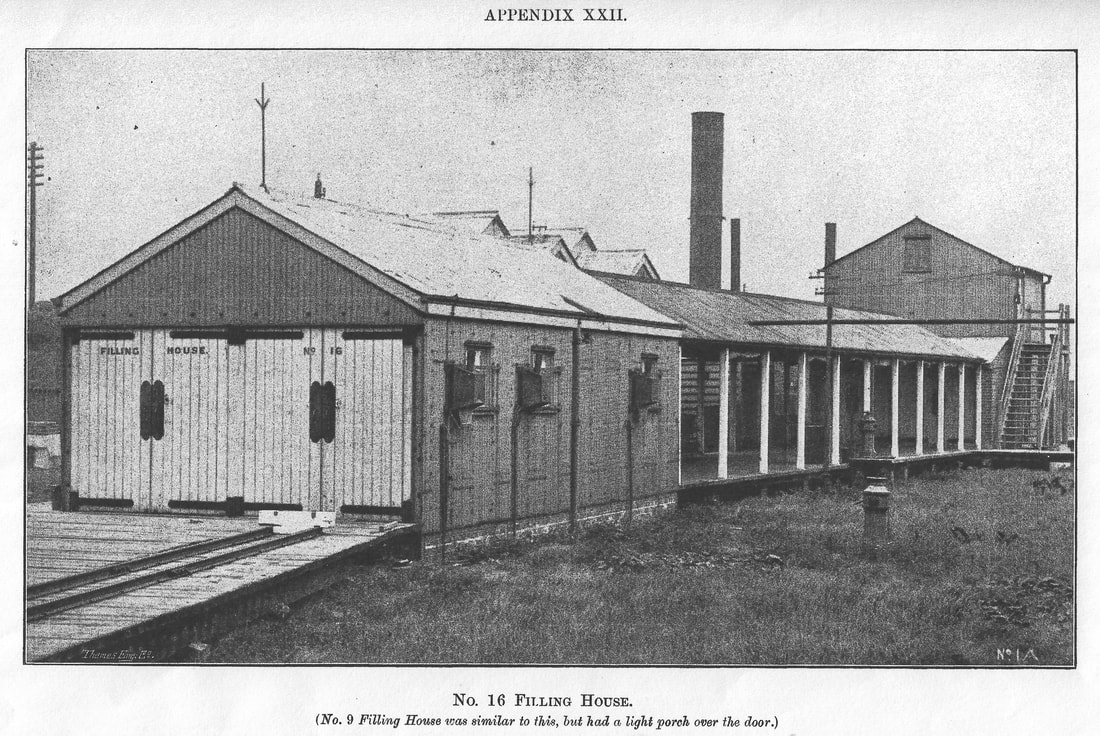

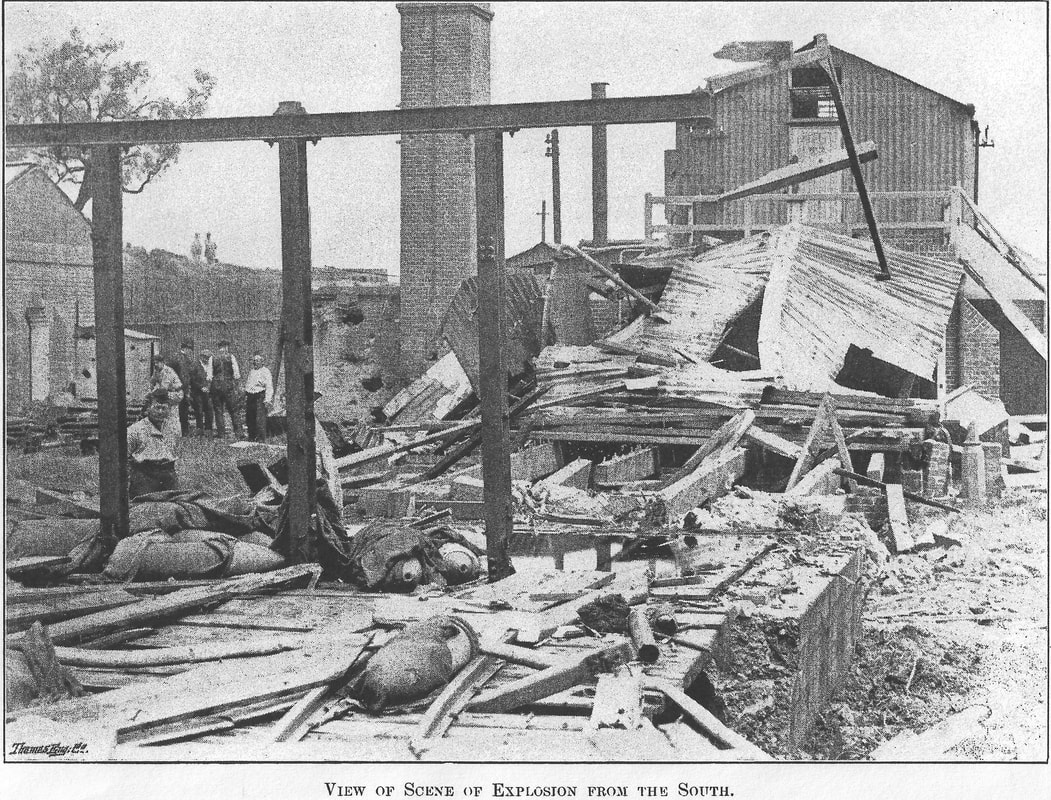

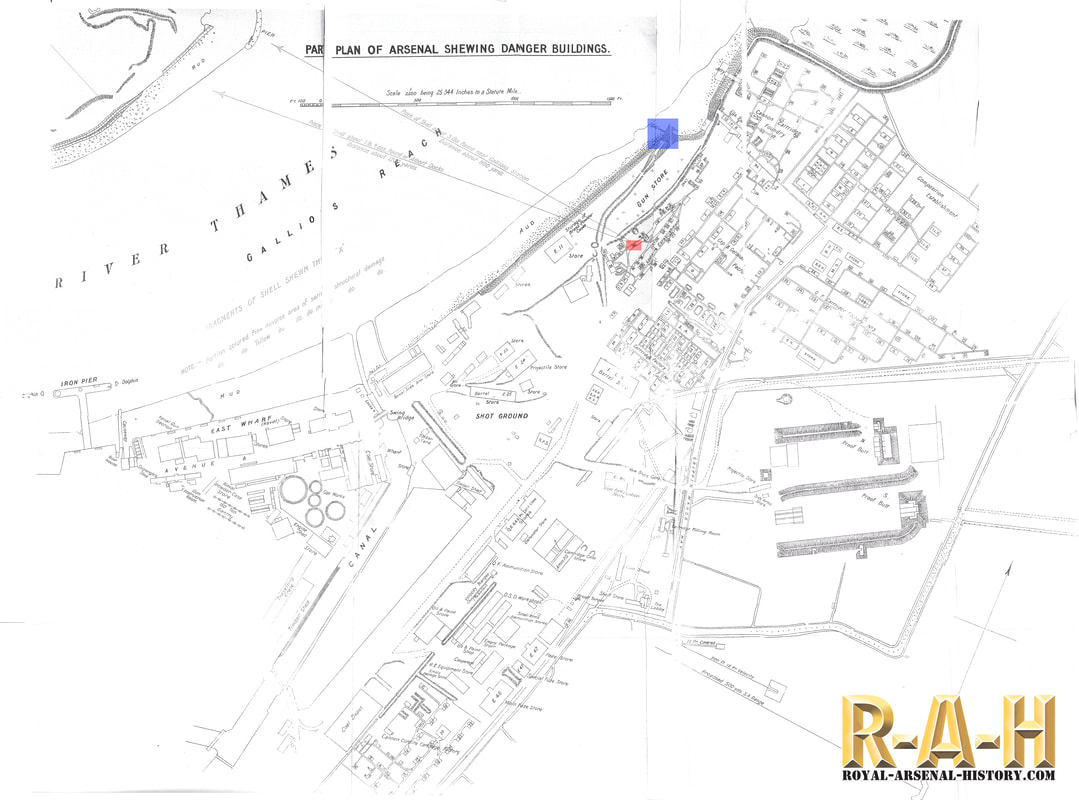

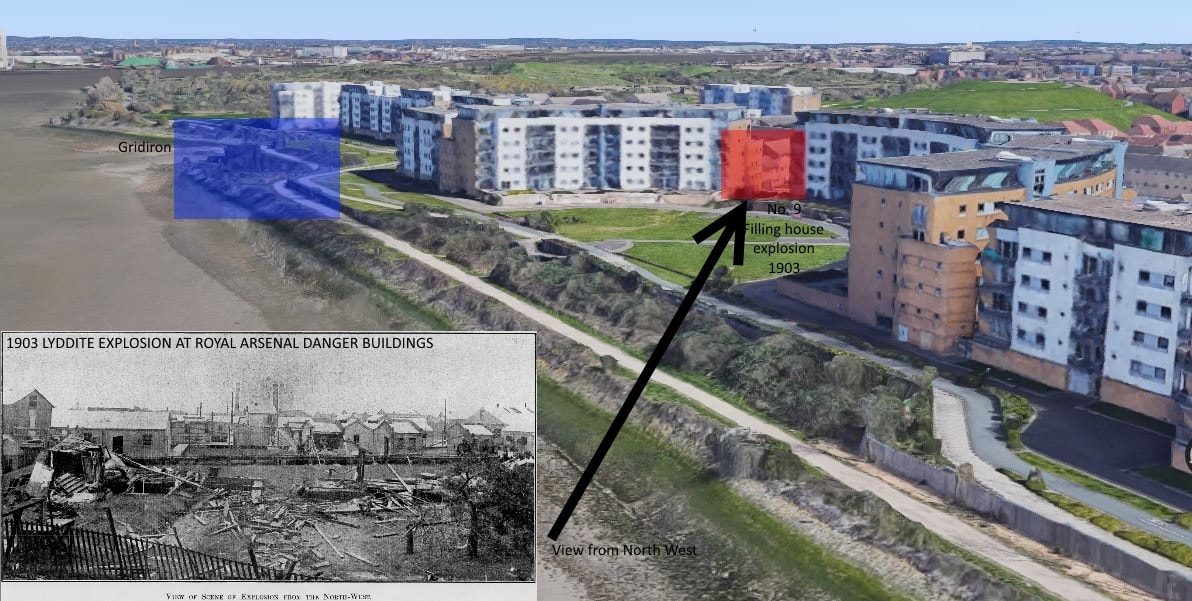

1903 Lyddite Establishment

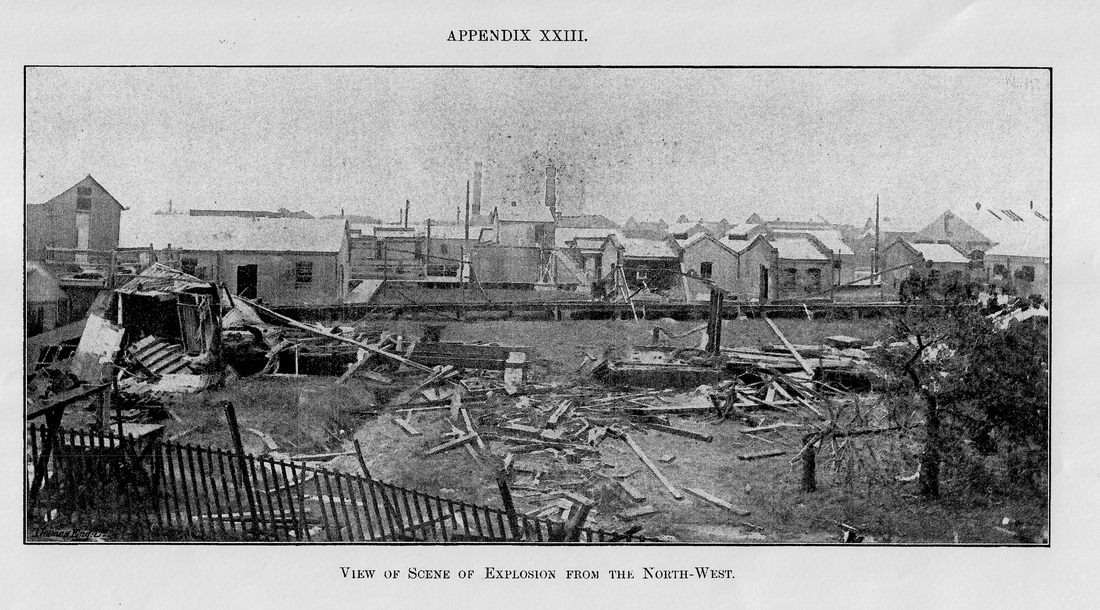

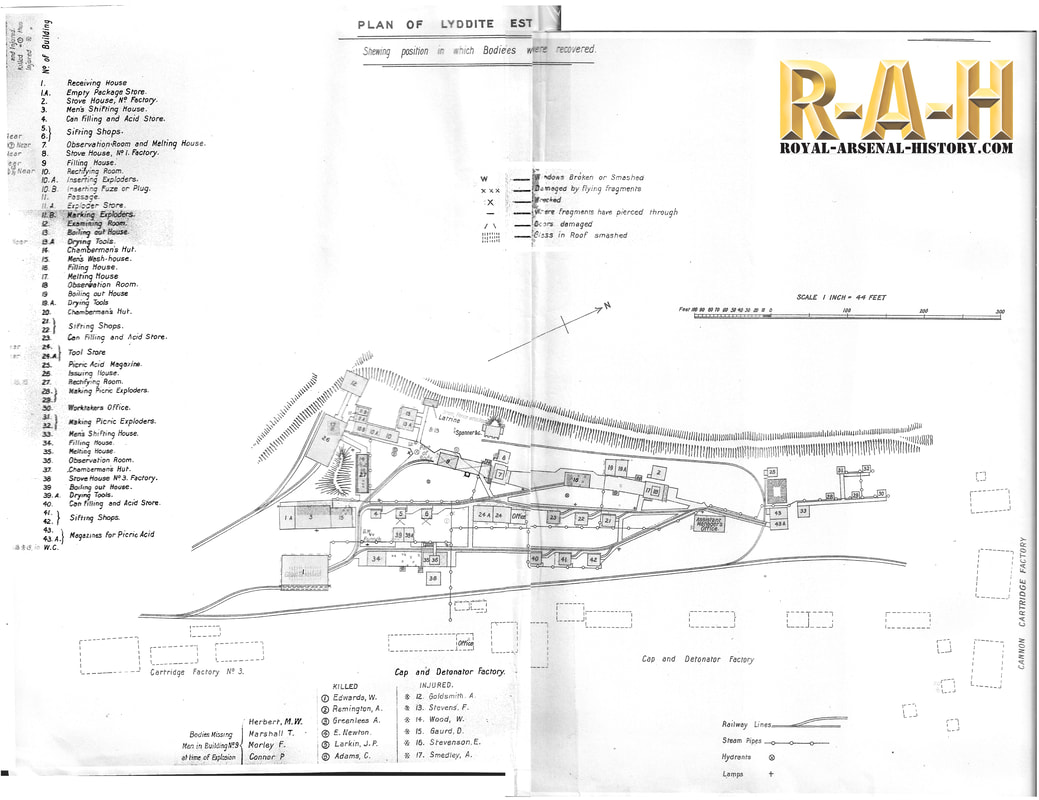

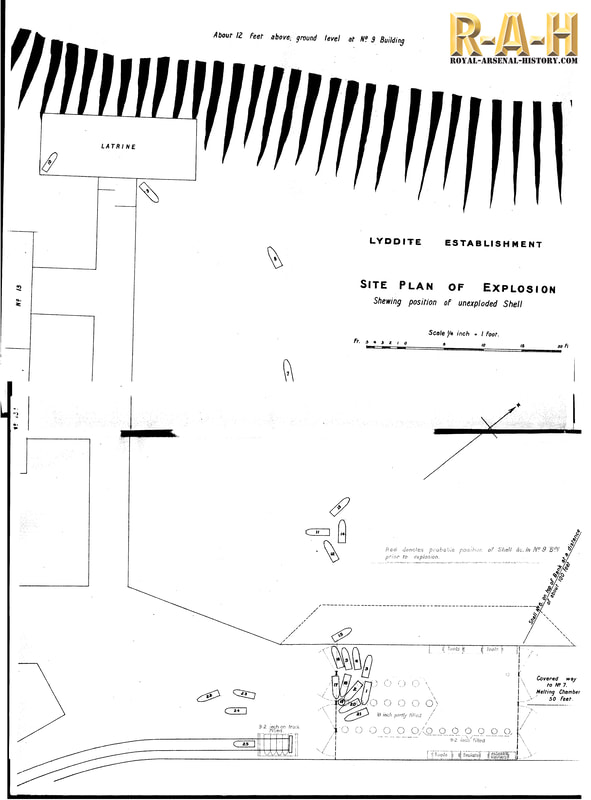

Investigation of the circumstances of an explosion which occurred in the Lyddite Establishment, Royal Laboratory, Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, on the 18th June 1903

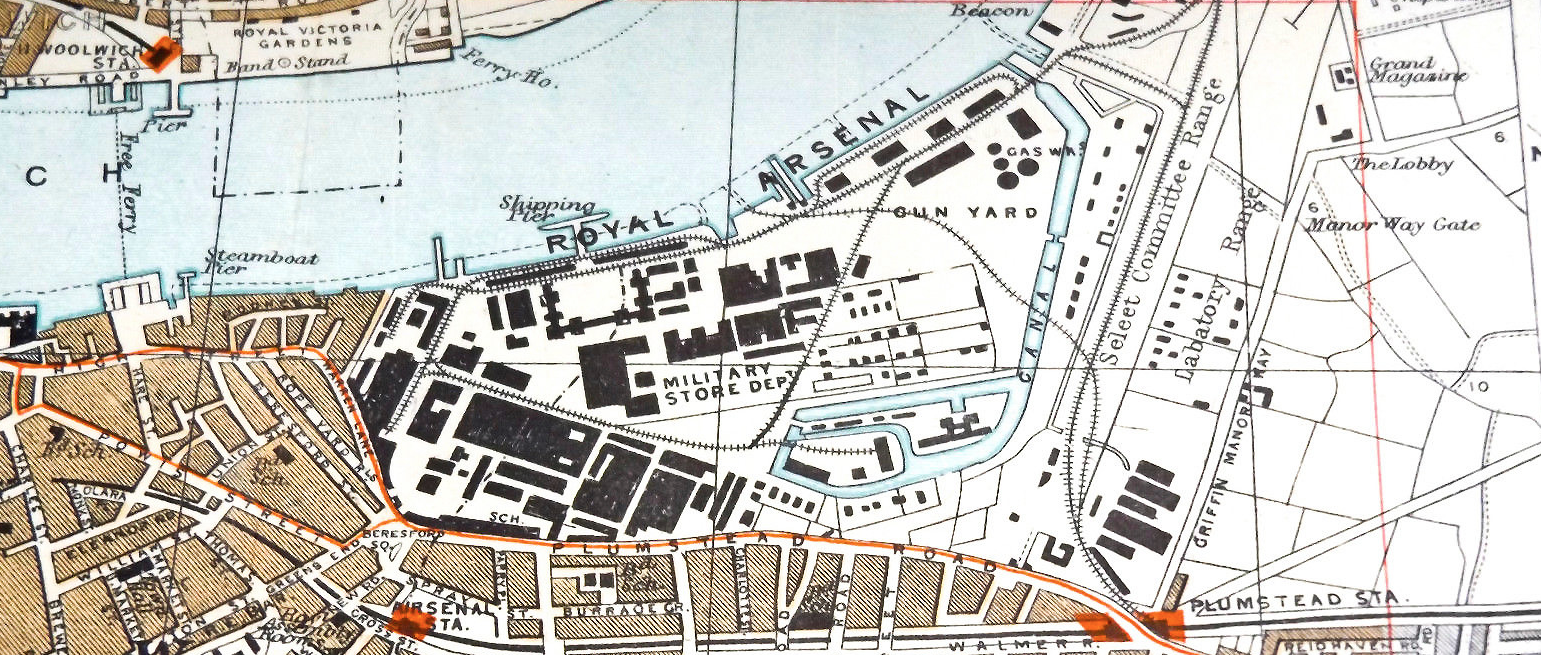

Location of number 9 filling house in red using the gridiron in blue as a reference for today.

Zoom in the following related 1903 explosion maps for finer details

Plan of Lyddite establishment showing various explicit details

120 Years later part of the fence survives

1903 Lyddite establishment site plan of explosion

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| 1903_lyddite_explosion_at_royal_arsenal_woolwich__r-a-h_.pdf | |

| File Size: | 6184 kb |

| File Type: | |

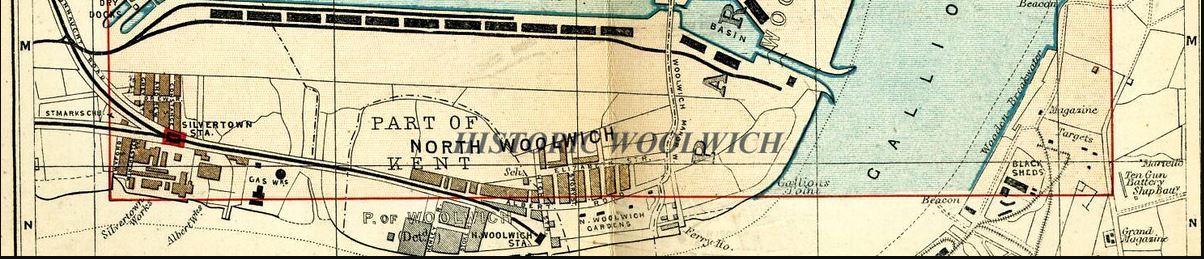

1907 Chemical Research Department on Plumstead marshes

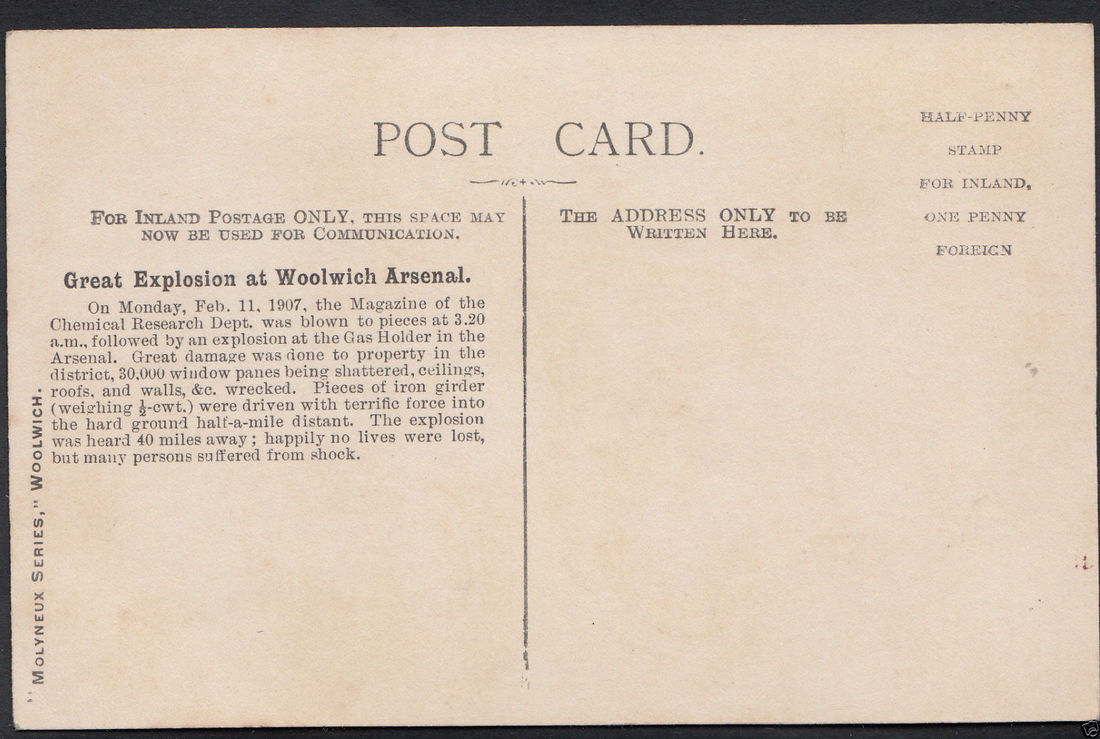

Great Explosion at Woolwich Arsenal.

This is the site of the Explosion in the Arsenal which happened in Feb' 1907.

The explosion happened at 3.20am on Feb' 11th 1907 in the Chemical research department on plumstead marshes near the river. A 15 meter deep crater was created and the explosion was heard for miles around

This is the site of the Explosion in the Arsenal which happened in Feb' 1907.

The explosion happened at 3.20am on Feb' 11th 1907 in the Chemical research department on plumstead marshes near the river. A 15 meter deep crater was created and the explosion was heard for miles around

On Monday, Feb 11. 1907 the Magazine of the Chemical Research Department was blown to pieces at 3.20am followed by an explosion at the Gas holder in the Arsenal Great damage was done to property in the district. 30,000 windows panes being shattered, ceilings, roofs and walls etc wrecked. Pieces of iron girder (weighing half cwt) were driven with terrific force into the hard ground hald a mile distant. The explosion was heard 40 miles away : happily no lives were lost, but many persons suffered from shock.

On Monday, Feb 11. 1907 the Magazine of the Chemical Research Department was blown to pieces at 3.20am followed by an explosion at the Gas holder in the Arsenal Great damage was done to property in the district. 30,000 windows panes being shattered, ceilings, roofs and walls etc wrecked. Pieces of iron girder (weighing half cwt) were driven with terrific force into the hard ground hald a mile distant. The explosion was heard 40 miles away : happily no lives were lost, but many persons suffered from shock.

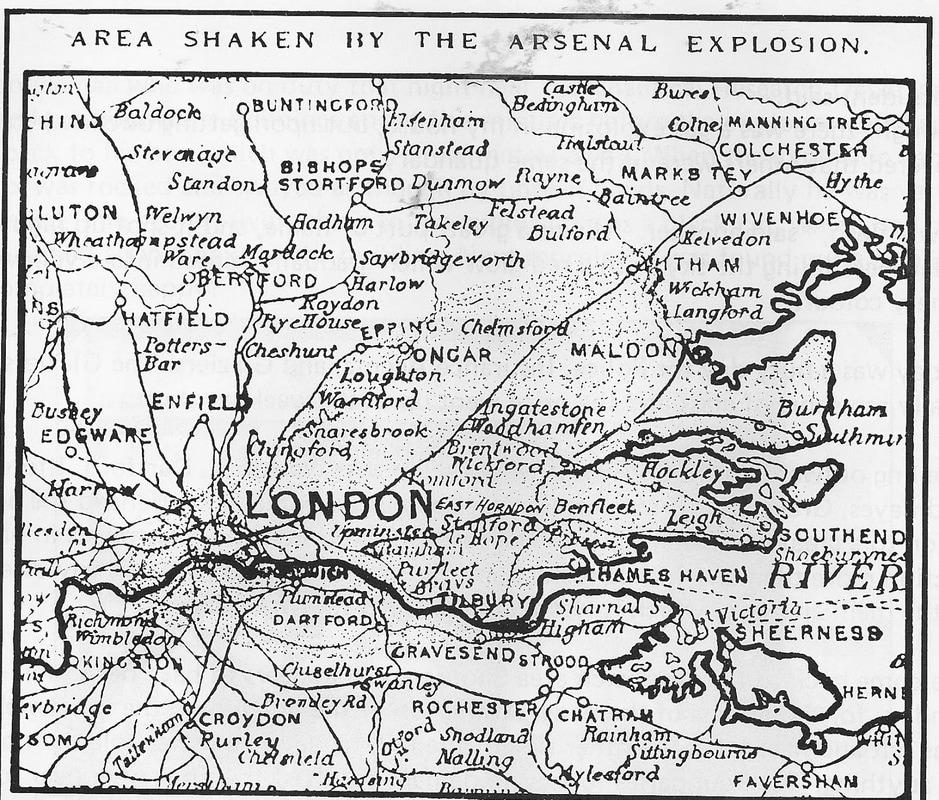

THE EXPLOSION AT WOOLWICH 1907.

The astonishing feature of the explosion at Woolwich Arsenal at the beginning of February was that nobody was killed or even injured. The explosion occurred in a magazine stored with cordite near the boundary of the Arsenal grounds on Plumstead Marshes. The cordite went off with a deafening roar, and the concussion must have been terrific. The building itself was reduced to a heap of rains, and other parts of the Arsenal were considerably damaged. One of tlie stands on the Arsenal Football Ground had the back completely torn away and the roof destroyed. A piece of masonry weighing 5 cwt was found 500 yds from where the cordite had dislodged it. The Arsenal gasometer was damaged, and thousands of feet of gas escaped. The force of the explosion caused an enormous breakage of windows throughout the whole length of the High street and the portion of Plumstead road nearest the marshes, and some of the adjoining streets. The concussion was felt as far away as Bishop, Stortford, in Hertfordshire. At Ilford in Essex, a large plate-glass window was blown out. At Romford windows and crockery were broken in many houses, and the same thing occurred at Leyton. At Woodford and Wanstead the church bells were heard to ring. In all the places named people were awakened from sleep, and many rushed into the streets. At Walthamstow a resident was roused by a series of crashes, and found a large overmantel, marble clock, and ornaments in fragments on the floor. Eye-witnesses of the scene which followed the explosion describe it as one of panic. Windows were thrown up, and scared 'householders, half dressed, made their way (reports our London correspondent) into the streets, where shouting, the barking of dogs, and the crash of falling glass added to the sense of terror. People hastily made their way to the Arsenal gates, for all guessed what had occurred. Here they were speedily assured by the policemen on duty that it was not believed that anyone had been killed or injured, a report which was confirmed an hour later by the assistant superintendent of the Royal Laboratory. Plumstead road was quickly as crowded as it usually is in the working hours of the day, and the news that the catastrophe was unaccompanied by loss of life was the subject of mutual congratulation among the residents. They had less reason for content when, after the first excitement, they surveyed their premises. In addition to the shattered windows numerous cases are reported of ceilings cracked, falls of plaster, ajid the smashing of breakable articles. Doors were blown open and latches wrenched away. In one case in Plumstead road a dividing wall between, two bedrooms collapsed and momentarily blinded the occupants with dust. In the rooms were sleeping several young men, assistants in (the dirapery store underneath. The pavements were littered with splintered glass and fragments of wood and mortar. When the first alarm had subsided shopkeepers and their households and assistants were busy clearing away the debris, and a timber merchant, with a quick eve to business, opened his store, where he was quickly inundated with orders for boarding to nail across shopfronts. Plate-glass insurance companies availed themselves of the occurrence to advertise their business, and flashes of humor were not wanting to relieve the serious side of the question. A pawnbroker hung out a placard bearing the legend " No glass; plenty brass," and in front of an eating-house, where every vestige of the shop window had disappeared was a notice in large letters : — " We are blown out; come in and we will blow you out."

It was a great piece of good fortune that the explosion did not take place in the daytime. Some 400 men are employed during the day in what is known as the danger zone, in which the Wrecked building stood, and it is matter for the utmost congratulation that the explosion took place at a time when the place was deserted except by the few policemen and watchmen on duty. Fortunately none of these happened to be at the time in the immediate vicinity of the magazine. Another congratulatory feature is that the magazine, which was the strongest building of the chemical research block, was surrounded by a broad, high mound of turf, which must have very greatly diminished the possibilities of damage to structures lying beyond. During Sunday night few men are employed at the Arsenal, and when the disaster occurred those employed at making up the fires had left. The explosion will throw about 150 men out of employment, as the research buildings in their present condition are not considered safe.

The astonishing feature of the explosion at Woolwich Arsenal at the beginning of February was that nobody was killed or even injured. The explosion occurred in a magazine stored with cordite near the boundary of the Arsenal grounds on Plumstead Marshes. The cordite went off with a deafening roar, and the concussion must have been terrific. The building itself was reduced to a heap of rains, and other parts of the Arsenal were considerably damaged. One of tlie stands on the Arsenal Football Ground had the back completely torn away and the roof destroyed. A piece of masonry weighing 5 cwt was found 500 yds from where the cordite had dislodged it. The Arsenal gasometer was damaged, and thousands of feet of gas escaped. The force of the explosion caused an enormous breakage of windows throughout the whole length of the High street and the portion of Plumstead road nearest the marshes, and some of the adjoining streets. The concussion was felt as far away as Bishop, Stortford, in Hertfordshire. At Ilford in Essex, a large plate-glass window was blown out. At Romford windows and crockery were broken in many houses, and the same thing occurred at Leyton. At Woodford and Wanstead the church bells were heard to ring. In all the places named people were awakened from sleep, and many rushed into the streets. At Walthamstow a resident was roused by a series of crashes, and found a large overmantel, marble clock, and ornaments in fragments on the floor. Eye-witnesses of the scene which followed the explosion describe it as one of panic. Windows were thrown up, and scared 'householders, half dressed, made their way (reports our London correspondent) into the streets, where shouting, the barking of dogs, and the crash of falling glass added to the sense of terror. People hastily made their way to the Arsenal gates, for all guessed what had occurred. Here they were speedily assured by the policemen on duty that it was not believed that anyone had been killed or injured, a report which was confirmed an hour later by the assistant superintendent of the Royal Laboratory. Plumstead road was quickly as crowded as it usually is in the working hours of the day, and the news that the catastrophe was unaccompanied by loss of life was the subject of mutual congratulation among the residents. They had less reason for content when, after the first excitement, they surveyed their premises. In addition to the shattered windows numerous cases are reported of ceilings cracked, falls of plaster, ajid the smashing of breakable articles. Doors were blown open and latches wrenched away. In one case in Plumstead road a dividing wall between, two bedrooms collapsed and momentarily blinded the occupants with dust. In the rooms were sleeping several young men, assistants in (the dirapery store underneath. The pavements were littered with splintered glass and fragments of wood and mortar. When the first alarm had subsided shopkeepers and their households and assistants were busy clearing away the debris, and a timber merchant, with a quick eve to business, opened his store, where he was quickly inundated with orders for boarding to nail across shopfronts. Plate-glass insurance companies availed themselves of the occurrence to advertise their business, and flashes of humor were not wanting to relieve the serious side of the question. A pawnbroker hung out a placard bearing the legend " No glass; plenty brass," and in front of an eating-house, where every vestige of the shop window had disappeared was a notice in large letters : — " We are blown out; come in and we will blow you out."

It was a great piece of good fortune that the explosion did not take place in the daytime. Some 400 men are employed during the day in what is known as the danger zone, in which the Wrecked building stood, and it is matter for the utmost congratulation that the explosion took place at a time when the place was deserted except by the few policemen and watchmen on duty. Fortunately none of these happened to be at the time in the immediate vicinity of the magazine. Another congratulatory feature is that the magazine, which was the strongest building of the chemical research block, was surrounded by a broad, high mound of turf, which must have very greatly diminished the possibilities of damage to structures lying beyond. During Sunday night few men are employed at the Arsenal, and when the disaster occurred those employed at making up the fires had left. The explosion will throw about 150 men out of employment, as the research buildings in their present condition are not considered safe.

Nearby Silver town Explosion of 1917

The Silvertown explosion occurred in Silvertown in West Ham, Essex (now part of the London Borough of Newham, in Greater London) on Friday, 19 January 1917 at 6.52 pm. The blast occurred at a munitions factory that was manufacturing explosives for Britain's World War I military effort. Approximately 50 long tons (50 tonnes) of trinitrotoluene (TNT) exploded, killing 73 people and injuring 400 more, as well as causing substantial damage in the local area.

National Filling factory No6 explosion Chilwell, Nottingham, 1st July 1918

In July 1918, just four months before the war's end, a devastating explosion tore through the factory, killing 134 people and injuring another 250, and causing the biggest explosive disaster in Britain’s history. The cause of the explosion remains a mystery to date. A small obelisk stands at the site to commemorate the victims of the disaster. The factory played an integral role in Britain's war effort, and the unexploded shells from that time are still being discovered today in Flanders Fields, with at least one fatality a year, and a dedicated Belgian army squad deals with the collection and destruction of the dormant shells.

The staggering demand for artillery shells posed a problem for a British army that was hopelessly ill-equipped at the war’s commencement. Woolwich arsenal could not match the demand, leading to such a shortfall of shells that, over a year into the war in 1915, artillery units were still having to heavily ration the number of shells they could fire in a day.

During World War One, there was a high demand for munitions, which led to an increase in the number of women working in factories. The Chilwell shell filling factory in Nottingham was no exception, where women played a vital role in the production of shells.

The staggering demand for artillery shells posed a problem for a British army that was hopelessly ill-equipped at the war’s commencement. Woolwich arsenal could not match the demand, leading to such a shortfall of shells that, over a year into the war in 1915, artillery units were still having to heavily ration the number of shells they could fire in a day. During World War One, there was a high demand for munitions, which led to an increase in the number of women working in factories. The Chilwell shell filling factory in Nottingham was no exception, where women played a vital role in the production of shells. The staggering demand for artillery shells posed a problem for a British army that was hopelessly ill-equipped at the war’s commencement. Woolwich arsenal could not match the demand, leading to such a shortfall of shells that, over a year into the war in 1915, artillery units were still having to heavily ration the number of shells they could fire in a day. During World War One, there was a high demand for munitions, which led to an increase in the number of women working in factories. The Chilwell shell filling factory in Nottingham was no exception, where women played a vital role in the production of shells.

The staggering demand for artillery shells posed a problem for a British army that was hopelessly ill-equipped at the war’s commencement. Woolwich arsenal could not match the demand, leading to such a shortfall of shells that, over a year into the war in 1915, artillery units were still having to heavily ration the number of shells they could fire in a day.

During World War One, there was a high demand for munitions, which led to an increase in the number of women working in factories. The Chilwell shell filling factory in Nottingham was no exception, where women played a vital role in the production of shells.

The staggering demand for artillery shells posed a problem for a British army that was hopelessly ill-equipped at the war’s commencement. Woolwich arsenal could not match the demand, leading to such a shortfall of shells that, over a year into the war in 1915, artillery units were still having to heavily ration the number of shells they could fire in a day. During World War One, there was a high demand for munitions, which led to an increase in the number of women working in factories. The Chilwell shell filling factory in Nottingham was no exception, where women played a vital role in the production of shells. The staggering demand for artillery shells posed a problem for a British army that was hopelessly ill-equipped at the war’s commencement. Woolwich arsenal could not match the demand, leading to such a shortfall of shells that, over a year into the war in 1915, artillery units were still having to heavily ration the number of shells they could fire in a day. During World War One, there was a high demand for munitions, which led to an increase in the number of women working in factories. The Chilwell shell filling factory in Nottingham was no exception, where women played a vital role in the production of shells.