Police and Fire Brigade

The Royal Arsenal's Eastwards expansion from the mid 1890s, which would almost double it's area, was in response to the need to securely store high-explosive munitions in isolation.

Firstly, land was leased but from 1903 freeholds were purchased in parcels until in 1907 the entirety of the Erith Marshes to the North of the Southern Outfall Sewer were in Crown hands, some additional 600 acres.

Construction of the Magazines was undertaken before all the surrounding land was in Crown hands and thus security was an immediate implication. In addition to its embrasure, blast-wall and narrow gauge feeder-railway each was surrounded by a Moat and within the Moat a high brick wall.

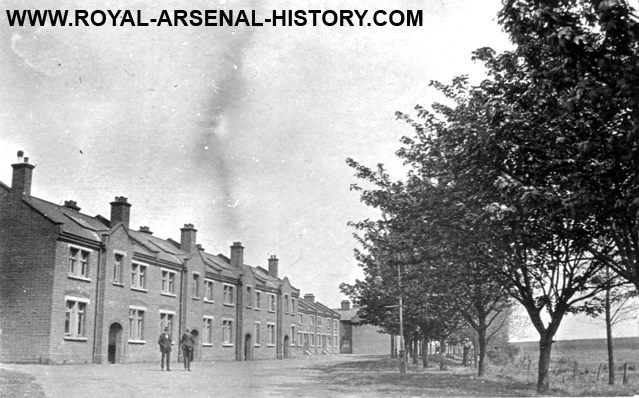

Such structures would require staff on an ongoing basis and accommodation was provided for Policemen, Firemen, Military and the Magazine Foreman.

The properties were ready for occupation in 1904 and were located either side of the original course of Harrow Manor Way.

Below Photo taken in 1904 credit: Hugh Gladden.

Firstly, land was leased but from 1903 freeholds were purchased in parcels until in 1907 the entirety of the Erith Marshes to the North of the Southern Outfall Sewer were in Crown hands, some additional 600 acres.

Construction of the Magazines was undertaken before all the surrounding land was in Crown hands and thus security was an immediate implication. In addition to its embrasure, blast-wall and narrow gauge feeder-railway each was surrounded by a Moat and within the Moat a high brick wall.

Such structures would require staff on an ongoing basis and accommodation was provided for Policemen, Firemen, Military and the Magazine Foreman.

The properties were ready for occupation in 1904 and were located either side of the original course of Harrow Manor Way.

Below Photo taken in 1904 credit: Hugh Gladden.

Their allocation was as follows.

Army Ordnance Dept., three Houses.

Royal Navy Armaments Dept., two Houses.

Police Constables, 44 Houses and 34 flats.

Polices Inspectors, two Houses.

Magazine Foreman, one House.

Army Ordnance Dept., three Houses.

Royal Navy Armaments Dept., two Houses.

Police Constables, 44 Houses and 34 flats.

Polices Inspectors, two Houses.

Magazine Foreman, one House.

There were also two Police 'Section Houses', presumably for single men. The Police accommodation was shared with a smaller number of Firemen.

The properties, of typical Victorian design, were of excellent quality and the Ministry upgraded them through the decades to maintain high standards. Given the isolation of these Quarters they were provided with Allotments, Chicken-runs and Piggeries from the outset. Children's education was provided by the London County Council at the School in nearby Crossness sewage pumping station.

This isolated community was over a mile from further habitation at Abbey Wood yet it functioned happily and largely self-sufficiently until the late 1950s. The Arsenal relinquished its Eastern parts to the London County Council in 1962 and the subsequent Greater London Council destroyed these Quarters as part of the Thamesmead project.

This isolated community was over a mile from further habitation at Abbey Wood yet it functioned happily and largely self-sufficiently until the late 1950s. The Arsenal relinquished its Eastern parts to the London County Council in 1962 and the subsequent Greater London Council destroyed these Quarters as part of the Thamesmead project.

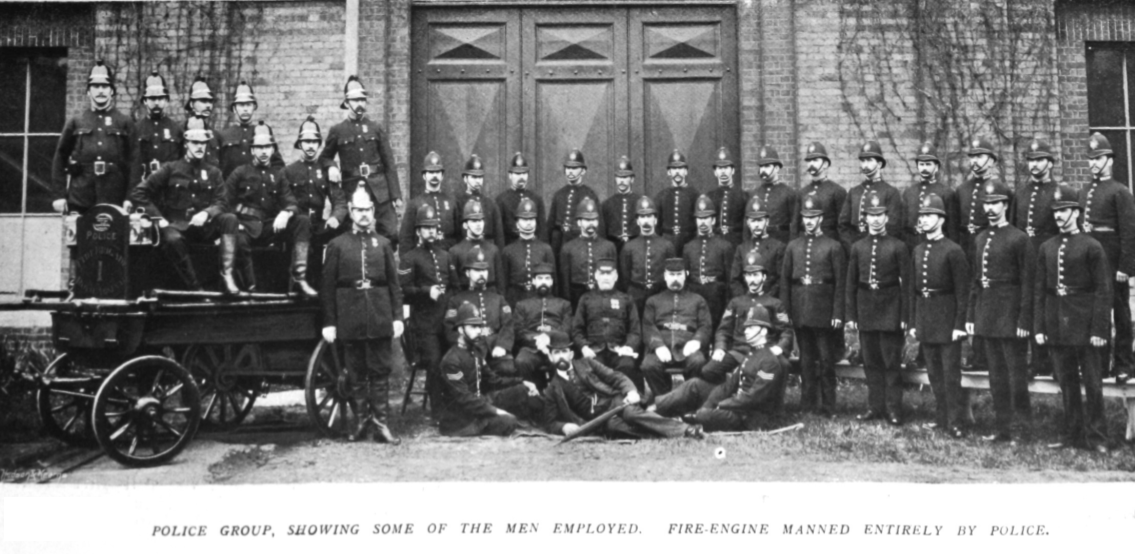

From Brig.Hogg's book: between about 1900 and 1920 the Arsenal Police were also given responsibility for fire-fighting and policemen became firemen when needed, so it's just about possible that the chap in Fire Brigade uniform might also have been a police officer (provided the photo was taken early enough). Hogg reckoned the Arsenal had one of the best-trained and best-equipped fire brigades in the country and up until at least the time of his writing (1963), it was independent and self-sustaining, and part of the Royal Arsenal Estate.

Police W D Constabulary (prior to 1967) In the early part of the eighteenth century the safe keeping of the Warren was in the custody of the Army. The guards were posted at the main and other guardrooms in the area and controlled the admission of visitors and kept watched on vagabonds. The Civil office and the Royal Laboratories each maintained a small band of watchman to patrol their premises at night. This system remained until August 1844 and the losses of larceny including nineteen brass howitzers, this lead to the introduction of the Metropolitan Police. In 1844 the strength of the force was one Inspector, one sergeant and nine constables, costing £557, 7s, 0d. In 1848 artificers and labourers of various departments were sworn in as special constables and by 1871 the strength had risen to 3 Inspectors, 10 Sergeants, 68 Constables and 1 Detective. From 1844 to 1861 police and troops had joint custody. In 1861, all troops were withdrawn with the exception of a small guard in the magazine area. In 1880 the Metropolitan police took overall control. In 1927 1 January the War Department Constabulary took over control. The Beresford Gate Building now located in the Beresford Square market area opposite the Royal Arsenal Estate was the headquarters of the police, On the first floor was the supertendant of police; also there was the C I D which consisted of two plain clothes detectives (we used to call these Mutt & Jeff ). On either side of the entrance were offices for supervisory staff for the booking in of visitors and personal property Also at the entrance were search boxes two each side. Regular searching took place ( The searching of females was more frequent at the third & fourth gates) To the right of the entrance was an escort office were visitors were escorted from to various departments. Next to Beresford Gate building was the police mess and accommodation for single police officers . To the left of the entrance to the mess was living quarters for the senior police staff. The Second, Third, Fourth and Harrow Manor gates also had search facilities. There was also a gate that only opened at certain times at the sewer bank between Fourth gate and Harrow gate, with steps over the sewer bank. At one time the fence at the eastern end of the Arsenal was electrified There was a River patrol if ships (coal ) tied up and they would have to check if there were any foreign persons on board and if they wished to go ashore they had to be escorted to an from. The police used to escort the `Pay Run` to outstations including the likes of Garland road, Mottingham and part of the R A Barracks & Fort Halstead. When I ( Ray Fordham ) returned from National Service to continue my apprenticership I regularlly accounted foot patrols on the Arsenal Estate and occasions during working hours I was stopped until they got to know me and recognised me as on Maintenance (M E D ). All personal leaving there shops before or after meal breaks had to have a note. Leaving work early to go out of the gate one had to have a pass signed by shop foreman or work taker Harrow Manorway was the married quarters of the police there was also a section house / social mess for the quarters.

Instructions for the police 1844/1855 Royal Arsenal

Arsenal Police force as a fire brigade 1858

Information from Hugh Gladden, his grandfather worked in the Royal Arsenal.

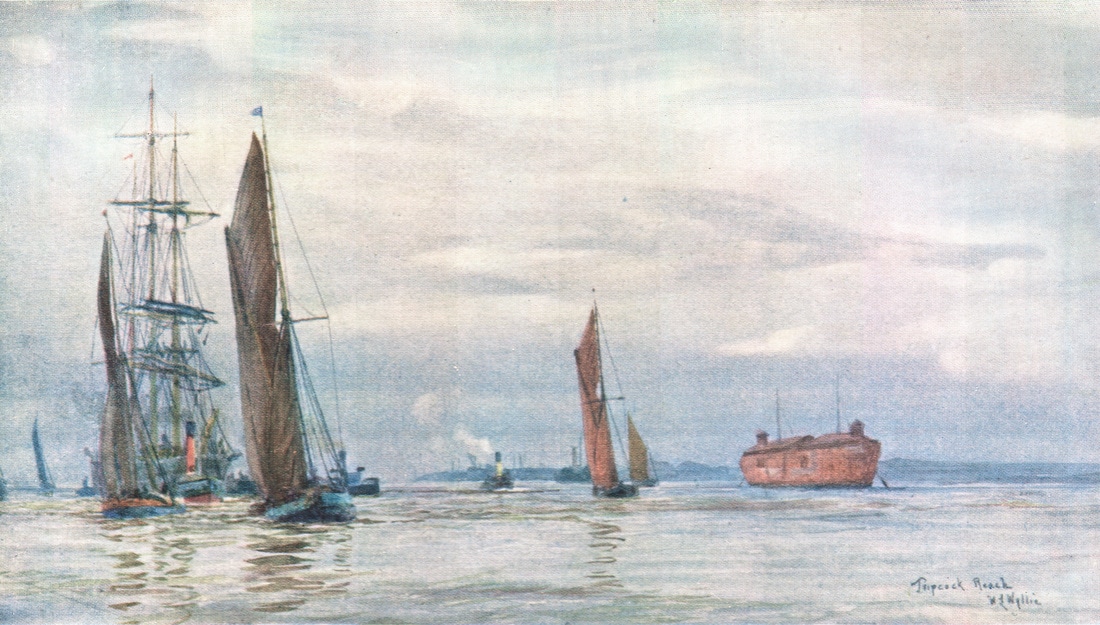

THALIA FLOATING MAGAZINE AT WOOLWICH ARSENAL

My Grandfather Fred Gladden joined the Metropolitan Police in 1890, and from then until his retirement in 1920 he served as a constable with Woolwich Dockyard Division, which at that time was responsible for policing Woolwich Arsenal and Woolwich Dockyard. My father was born in 1904, by which time the family were living at 21 Police Quarters, at Crossness. Dad attended Crossness Primary School (in the grounds of the Outfall Works) and then St. Augustine’s in Belvedere.

Dad told me that one of his father’s duties was to row out to an old ‘powder hulk’ moored in the Thames, to check on security and so forth. The kids would sit on the riverbank and wait for him to return. Dad reckoned his father and his colleagues would sit around on board the hulk, smoking their pipes! He also told me that the only illumination allowed on board was from candles – which seems insane until you realise that if you knock over a candle it tends to go out, whereas an oil-lamp might break and start a fire? Nevertheless, the thought of them smoking pipes on board a ship capable of storing 900 tons of explosives is a bit scary! There would have been a few broken windows in Woolwich if she’d gone up. Perhaps my Dad was pulling my leg.

When I started doing some family research, I found that the powder hulk was ex-HMS Thalia, an old warship. This is what I have found out about her:

‘Thalia’ was a Juno class corvette and was the last ship to be completed at Woolwich Dockyard before that became merely a stores depot (I believe that her hull was built at Deptford Dockyard before it was closed). She was a fully-rigged ‘transition period’ ship with a wooden hull and steam-powered screw propulsion to augment her sails. She was commissioned into the Royal Navy in 1869 or 1871 (accounts vary) and spent the next twenty-odd years of service sailing to China, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, among other places – including, in 1886, Tristan da Cunha. She was decommissioned in 1891, had her engine and rigging removed and was converted to a powder hulk. This much seems to be generally agreed.

However, there is an assertion repeated on several internet ‘naval history’ websites that after the end of her service with the Royal Navy, Thalia was moored at Portsmouth as a powder-hulk: my research suggests that this is a mistake. I suggest that it may be a case of serial copying of an error, its repetition perhaps due to a tendency for some website authors to repeat perceived ‘facts’, without checking sources sufficiently.

I suggest that the evidence that follows shows beyond any reasonable doubt that her days as a powder-hulk were spent, not in Portsmouth, but in the service of Woolwich Royal Arsenal, moored at Tripcock Reach, adjacent to the then Cannon Cartridge Factory.

In roughly chronological order:

1.

There are several references to Thalia in Brigadier O.F.G. Hogg’s ‘The Royal Arsenal: its Background, Origin and History’ (Oxford University Press, London, 1963). Hogg records (volume 2, page 891) the findings of the Sandhurst Committee in 1895, which included the recommendation that ‘Thalia floating magazine, if continued, to be placed in a safer position’. Elsewhere, (page 931) he records the Committee’s observation that “The position of this magazine which has a capacity of 18,000 barrels (900 tons), and which actually contained at the time of the Committee’s enquiry 300 tons of powder in barrels and in cannon cartridges, is, in the opinion of the Committee, one to justify anxiety. The evil seems to be seriously aggravated by the proximity of the magazine to the Cannon Cartridge Establishment, the two being a mutual menace”.

2.

There is a record in the archives of the Peninsular and Orient Steamship Line (‘P&O’) that specifically names the Thalia as a powder hulk that was in collision with a P&O passenger ship near Tripcock Point on January 23rd, 1896. Under the entry for S.S. Shannon, it reads: 23.01.1896: In collision with the powder hulk Thalia off Royal Albert Dock,

London but without significant damage. Thalia was reported to have broken her moorings and ran aground above Tripcock Point.

To account for Thalia’s reported position at the time of the collision it must be assumed that her moorings were broken on the rising tide and that she then drifted upstream on the flood, where she collided with the SS Shannon, outward bound for Bombay (Mumbai), off the entrance to The Royal Albert Dock. Fortunately, there was no damage and the Thalia didn’t explode. It seems that on the ebb tide she drifted back downstream and obligingly grounded herself at Tripcock Point. By that time, I believe she had been a powder hulk on the Thames for five years.

3.

In the volume mentioned above in item 1, Hogg goes on to report (pages 931 – 932) that in 1901 three named senior officers at The Royal Arsenal commented “We consider the Thalia floating magazine a great source of danger. Twice her mooring chains have been broken by passing vessels and part of her rail has been carried away. Vessels with smoking funnels pass quite close to her. The Thalia should be disused at once and the use of floating magazines discontinued.”

4.

Hogg also records (page 924) that in 1902, 315 acres of land was purchased ‘for the storage of explosives in place of the floating magazine Thalia’. This entry suggests that Thalia then ‘disappeared from the Woolwich scene’: this may be an assumption of good intention rather than a record of events, as points 5 and 6 that follow here should make clear.

5.

In 1905, the maritime painter William Lionel Wyllie published a book in collaboration with his wife Marion, called London to The Nore (A. & C. Black, London). It was an account of their journey by Thames sailing barge from Westminster to Rochester. Marion wrote the text and William illustrated the book with many watercolours, one of which he called ‘Tripcock Reach’. It is listed on the contents page and captioned as ‘Tripcock’s Reach – the old Powder-hulk “Thalia” ‘. Marion wrote (page 92) “…..we tack and make a board towards the powder-hulk, once H.M. Armed Storeship Thalia.” (She goes on to recount a story about Thalia’s failure to perform sail-drills to the satisfaction of the Admiral while serving in the Mediterranean and her subsequent exclusion from Fleet sail-drills.) Curiously, Marion makes no mention of the dates of their voyage, but I assume it was probably the year before publication, in other words 1904.

6.

In 1907, on July 12th, The London Gazette published some regulations governing the movement of shipping on the Thames, in which Thalia is named: “No steam vessel shall be worked, navigated or placed upon or anchored or moored in the river within three hundred and sixty feet of His Majesty's dock-yard or arsenal at Woolwich or of His Majesty's victualling yard at Deptford except steam vessels belonging to or employed in the service of His Majesty, his heirs or successors and no vessel shall be anchored in the river within a similar distance of His Majesty's powder hulk " Thalia " except for the purpose of loading or discharging explosives out of or into such powder hulk.” (Paragraph number 50)

The same notice, with only very minor variations to the text (e.g. ‘the powder hulk ''Thalia" belonging to Her Majesty lying off the said arsenal’), had also been posted in The London Gazette in April 1897 (page 1959, para 12) and appeared once more in November 1911 (page 8070, para 51).

On the basis of the above evidence therefore, it is possible with a high degree of confidence to place Thalia in the vicinity of Tripcock Reach as a floating magazine in 1895, in 1896, in 1897, in 1901, in 1902, in 1904, in 1907 and in 1911. I have not been able to find any credible evidence to place her at Portsmouth at any date whatsoever. There are however references to a previous HMS Thalia that was apparently hulked at Portsmouth in 1855, where she is said to have served as a Roman Catholic chapel ship until broken up at Cowes in 1867: perhaps that is the source of the confusion?

Nevertheless, there is a period of just over three years between the last 1911 London Gazette notice and the Colledge entry for 1915 (see below) that is as yet unaccounted for: in theory, Thalia could have been transferred to Portsmouth during that time, although that might seem unlikely.

There are references in Naval Service records and War Graves inscriptions to a ship named Thalia based at Cromarty during WW1. One website cites an entry which it claims to be from a book called British Warships 1914-1919, by F.J.Dittmar & J.J.Colledge. It reads: “THALIA, harbour service, store hulk, Cromarty; base ship 2.15 (ex-wooden screw corvette, Juno-class), built 1869, 2240 tons. Sold 16.9.20.”. The current edition of ‘Ships of the Royal Navy, by J.J.Colledge & Ben Warlow, (Casemate, 2010), also records Thalia as being commissioned as a ‘base ship’ in February 1915, and then sold to Rose Street Foundry in Inverness in September 1920, although it makes no reference to where she served as a base ship. Neither entry states why Rose Street Foundry bought her, although it has been assumed that it was for breaking.

Elsewhere, it is claimed that this Thalia was the ‘mothership’ for Area IV of the Auxiliary Patrol anti-submarine and mine-sweeping service for the Cromarty Firth, which was established between December 1914 and August 1915.

I believe that J.J.Colledge is generally regarded as a reliable authority on such matters and that the books he authored are standard reference works for naval historians. It seems likely therefore that there was a base ship at Cromarty called Thalia, and her proposed fate in Inverness, twenty miles or so distant from Cromarty is therefore at least plausible. I have however three concerns with the Cromarty scenario as an account of the fate of the ‘Woolwich Thalia’:

First, assuming that they are the same ship, it seems extraordinary that it was considered worth the expense and considerable risk to tow such a venerable hulk (she would have been over 40 years old at the time) about 600 miles from Woolwich to Cromarty, through the North Sea, with WW1 having already begun (there was no need for such a ‘mothership’ until the Auxiliary Patrols were formed in 1915, so it would seem unlikely that she would have been moved to Cromarty before then). Were suitable candidates for base-ships really so hard to come by in the Cromarty Firth?

Second, I can find no reference to Rose Street Foundry being engaged in ship-breaking activities in Inverness. It seems at least part of their business was as marine engineers and there are accounts of their involvement in repairing coasters and fishing vessels, but I have found no mention of them being involved in ship-breaking or scrap activities.

Third, if the ship in question was the Thalia previously at Woolwich, one has to ask what Rose Street Foundry - who were engineers in metal - would want with the hull of a large wooden ship. It is possible that, like Cutty Sark (built at around the same time), Thalia was of composite construction with iron frames, and with external copper or Muntz metal sheathing beneath the waterline. If so, it might have been financially worthwhile to buy her and to tow her the twenty miles to Inverness for breaking. Unfortunately, I have not been able to discover any details of the precise method used in the construction of HMS Thalia so I cannot say with any confidence that she was of composite construction. Nor do I know the relative value at the time of wrought iron frames, or of Muntz metal, or the costs of towage and breaking, or indeed what was paid for the hulk - so I cannot make any informed judgement of the economic case, although it might seem an improbable way for Rose Street Foundry to make a profit.

On the other hand, neither have I been able to find any evidence on which to base an alternative account of her fate, so it remains theoretically possible that she was towed to Cromarty for use as a Base Ship and that she was eventually scrapped in Inverness.

Dad told me that one of his father’s duties was to row out to an old ‘powder hulk’ moored in the Thames, to check on security and so forth. The kids would sit on the riverbank and wait for him to return. Dad reckoned his father and his colleagues would sit around on board the hulk, smoking their pipes! He also told me that the only illumination allowed on board was from candles – which seems insane until you realise that if you knock over a candle it tends to go out, whereas an oil-lamp might break and start a fire? Nevertheless, the thought of them smoking pipes on board a ship capable of storing 900 tons of explosives is a bit scary! There would have been a few broken windows in Woolwich if she’d gone up. Perhaps my Dad was pulling my leg.

When I started doing some family research, I found that the powder hulk was ex-HMS Thalia, an old warship. This is what I have found out about her:

‘Thalia’ was a Juno class corvette and was the last ship to be completed at Woolwich Dockyard before that became merely a stores depot (I believe that her hull was built at Deptford Dockyard before it was closed). She was a fully-rigged ‘transition period’ ship with a wooden hull and steam-powered screw propulsion to augment her sails. She was commissioned into the Royal Navy in 1869 or 1871 (accounts vary) and spent the next twenty-odd years of service sailing to China, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, among other places – including, in 1886, Tristan da Cunha. She was decommissioned in 1891, had her engine and rigging removed and was converted to a powder hulk. This much seems to be generally agreed.

However, there is an assertion repeated on several internet ‘naval history’ websites that after the end of her service with the Royal Navy, Thalia was moored at Portsmouth as a powder-hulk: my research suggests that this is a mistake. I suggest that it may be a case of serial copying of an error, its repetition perhaps due to a tendency for some website authors to repeat perceived ‘facts’, without checking sources sufficiently.

I suggest that the evidence that follows shows beyond any reasonable doubt that her days as a powder-hulk were spent, not in Portsmouth, but in the service of Woolwich Royal Arsenal, moored at Tripcock Reach, adjacent to the then Cannon Cartridge Factory.

In roughly chronological order:

1.

There are several references to Thalia in Brigadier O.F.G. Hogg’s ‘The Royal Arsenal: its Background, Origin and History’ (Oxford University Press, London, 1963). Hogg records (volume 2, page 891) the findings of the Sandhurst Committee in 1895, which included the recommendation that ‘Thalia floating magazine, if continued, to be placed in a safer position’. Elsewhere, (page 931) he records the Committee’s observation that “The position of this magazine which has a capacity of 18,000 barrels (900 tons), and which actually contained at the time of the Committee’s enquiry 300 tons of powder in barrels and in cannon cartridges, is, in the opinion of the Committee, one to justify anxiety. The evil seems to be seriously aggravated by the proximity of the magazine to the Cannon Cartridge Establishment, the two being a mutual menace”.

2.

There is a record in the archives of the Peninsular and Orient Steamship Line (‘P&O’) that specifically names the Thalia as a powder hulk that was in collision with a P&O passenger ship near Tripcock Point on January 23rd, 1896. Under the entry for S.S. Shannon, it reads: 23.01.1896: In collision with the powder hulk Thalia off Royal Albert Dock,

London but without significant damage. Thalia was reported to have broken her moorings and ran aground above Tripcock Point.

To account for Thalia’s reported position at the time of the collision it must be assumed that her moorings were broken on the rising tide and that she then drifted upstream on the flood, where she collided with the SS Shannon, outward bound for Bombay (Mumbai), off the entrance to The Royal Albert Dock. Fortunately, there was no damage and the Thalia didn’t explode. It seems that on the ebb tide she drifted back downstream and obligingly grounded herself at Tripcock Point. By that time, I believe she had been a powder hulk on the Thames for five years.

3.

In the volume mentioned above in item 1, Hogg goes on to report (pages 931 – 932) that in 1901 three named senior officers at The Royal Arsenal commented “We consider the Thalia floating magazine a great source of danger. Twice her mooring chains have been broken by passing vessels and part of her rail has been carried away. Vessels with smoking funnels pass quite close to her. The Thalia should be disused at once and the use of floating magazines discontinued.”

4.

Hogg also records (page 924) that in 1902, 315 acres of land was purchased ‘for the storage of explosives in place of the floating magazine Thalia’. This entry suggests that Thalia then ‘disappeared from the Woolwich scene’: this may be an assumption of good intention rather than a record of events, as points 5 and 6 that follow here should make clear.

5.

In 1905, the maritime painter William Lionel Wyllie published a book in collaboration with his wife Marion, called London to The Nore (A. & C. Black, London). It was an account of their journey by Thames sailing barge from Westminster to Rochester. Marion wrote the text and William illustrated the book with many watercolours, one of which he called ‘Tripcock Reach’. It is listed on the contents page and captioned as ‘Tripcock’s Reach – the old Powder-hulk “Thalia” ‘. Marion wrote (page 92) “…..we tack and make a board towards the powder-hulk, once H.M. Armed Storeship Thalia.” (She goes on to recount a story about Thalia’s failure to perform sail-drills to the satisfaction of the Admiral while serving in the Mediterranean and her subsequent exclusion from Fleet sail-drills.) Curiously, Marion makes no mention of the dates of their voyage, but I assume it was probably the year before publication, in other words 1904.

6.

In 1907, on July 12th, The London Gazette published some regulations governing the movement of shipping on the Thames, in which Thalia is named: “No steam vessel shall be worked, navigated or placed upon or anchored or moored in the river within three hundred and sixty feet of His Majesty's dock-yard or arsenal at Woolwich or of His Majesty's victualling yard at Deptford except steam vessels belonging to or employed in the service of His Majesty, his heirs or successors and no vessel shall be anchored in the river within a similar distance of His Majesty's powder hulk " Thalia " except for the purpose of loading or discharging explosives out of or into such powder hulk.” (Paragraph number 50)

The same notice, with only very minor variations to the text (e.g. ‘the powder hulk ''Thalia" belonging to Her Majesty lying off the said arsenal’), had also been posted in The London Gazette in April 1897 (page 1959, para 12) and appeared once more in November 1911 (page 8070, para 51).

On the basis of the above evidence therefore, it is possible with a high degree of confidence to place Thalia in the vicinity of Tripcock Reach as a floating magazine in 1895, in 1896, in 1897, in 1901, in 1902, in 1904, in 1907 and in 1911. I have not been able to find any credible evidence to place her at Portsmouth at any date whatsoever. There are however references to a previous HMS Thalia that was apparently hulked at Portsmouth in 1855, where she is said to have served as a Roman Catholic chapel ship until broken up at Cowes in 1867: perhaps that is the source of the confusion?

Nevertheless, there is a period of just over three years between the last 1911 London Gazette notice and the Colledge entry for 1915 (see below) that is as yet unaccounted for: in theory, Thalia could have been transferred to Portsmouth during that time, although that might seem unlikely.

There are references in Naval Service records and War Graves inscriptions to a ship named Thalia based at Cromarty during WW1. One website cites an entry which it claims to be from a book called British Warships 1914-1919, by F.J.Dittmar & J.J.Colledge. It reads: “THALIA, harbour service, store hulk, Cromarty; base ship 2.15 (ex-wooden screw corvette, Juno-class), built 1869, 2240 tons. Sold 16.9.20.”. The current edition of ‘Ships of the Royal Navy, by J.J.Colledge & Ben Warlow, (Casemate, 2010), also records Thalia as being commissioned as a ‘base ship’ in February 1915, and then sold to Rose Street Foundry in Inverness in September 1920, although it makes no reference to where she served as a base ship. Neither entry states why Rose Street Foundry bought her, although it has been assumed that it was for breaking.

Elsewhere, it is claimed that this Thalia was the ‘mothership’ for Area IV of the Auxiliary Patrol anti-submarine and mine-sweeping service for the Cromarty Firth, which was established between December 1914 and August 1915.

I believe that J.J.Colledge is generally regarded as a reliable authority on such matters and that the books he authored are standard reference works for naval historians. It seems likely therefore that there was a base ship at Cromarty called Thalia, and her proposed fate in Inverness, twenty miles or so distant from Cromarty is therefore at least plausible. I have however three concerns with the Cromarty scenario as an account of the fate of the ‘Woolwich Thalia’:

First, assuming that they are the same ship, it seems extraordinary that it was considered worth the expense and considerable risk to tow such a venerable hulk (she would have been over 40 years old at the time) about 600 miles from Woolwich to Cromarty, through the North Sea, with WW1 having already begun (there was no need for such a ‘mothership’ until the Auxiliary Patrols were formed in 1915, so it would seem unlikely that she would have been moved to Cromarty before then). Were suitable candidates for base-ships really so hard to come by in the Cromarty Firth?

Second, I can find no reference to Rose Street Foundry being engaged in ship-breaking activities in Inverness. It seems at least part of their business was as marine engineers and there are accounts of their involvement in repairing coasters and fishing vessels, but I have found no mention of them being involved in ship-breaking or scrap activities.

Third, if the ship in question was the Thalia previously at Woolwich, one has to ask what Rose Street Foundry - who were engineers in metal - would want with the hull of a large wooden ship. It is possible that, like Cutty Sark (built at around the same time), Thalia was of composite construction with iron frames, and with external copper or Muntz metal sheathing beneath the waterline. If so, it might have been financially worthwhile to buy her and to tow her the twenty miles to Inverness for breaking. Unfortunately, I have not been able to discover any details of the precise method used in the construction of HMS Thalia so I cannot say with any confidence that she was of composite construction. Nor do I know the relative value at the time of wrought iron frames, or of Muntz metal, or the costs of towage and breaking, or indeed what was paid for the hulk - so I cannot make any informed judgement of the economic case, although it might seem an improbable way for Rose Street Foundry to make a profit.

On the other hand, neither have I been able to find any evidence on which to base an alternative account of her fate, so it remains theoretically possible that she was towed to Cromarty for use as a Base Ship and that she was eventually scrapped in Inverness.