Convicts

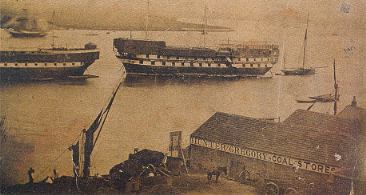

This remarkable and unique photograph shows the Woolwich convict hulks at the end of their life moored at the end of Warren Lane (Royal Arsenal Gardens today). Old, dismasted warship hulls, they were doomed to be broken and burnt. Between 1776 and 1857 they housed a floating prison population at Woolwich in conditions of grim austerity.

Floating prisons that housed London's convicts known as Hulks

Known as prison ships or “prison hulks”, these decomissioned vessels were used by Britain during the 18th and 19th centuries to house prisoners of war and those awaiting transportation to penal colonies. Rife with death, disease and despair, prison ships reflect a less-than-proud corner of Britain’s impressive maritime history. Moreover, some converted hulks were among the Royal Navy’s most celebrated vessels. The use of the hulks was seen as a temporary measure, and so was first authorized by Parliament for only two years. But despite the concerns of some members who deplored its inhumanity, the 1776 Act lasted for 80 years. It was regularly renewed and extended in scope 'for the more severe and effectual punishment of atrocious and daring offenders'.

The first hulks were moored on the Thames off Woolwich and the opposite shore. In the 18th century there were marshes along the north shore and few people lived there. On the southern shore, the Woolwich Warren was a maze of workshops, warehouses, wood-yards, barracks, foundries and firing ranges.

The first hulks were moored on the Thames off Woolwich and the opposite shore. In the 18th century there were marshes along the north shore and few people lived there. On the southern shore, the Woolwich Warren was a maze of workshops, warehouses, wood-yards, barracks, foundries and firing ranges.

Hard labour - Putting the convicts to work

Convicts were put to work at the Woolwich Arsenal. Transporting convicts to America had cost the Crown little. But housing convicts on the hulks was expensive, even though the clothing, food and accommodation were of the lowest quality. To cover the cost, the convicts were put to work improving the river. By about 1775 it was clear that the Thames' main channel was drifting toward the centre of the river. Major dredging needed to be done to stop the movement.

Convict labour was also needed for the development of the Arsenal and the nearby docks. The men dug canals and built the walls around the Arsenal. Other convicts were put to work driving in posts to protect the riverbanks from erosion.

The convicts worked long hours on the banks of the Thames and at the dockyards at Woolwich: 10 hours during summer, 7 in the winter.

Convict labour was also needed for the development of the Arsenal and the nearby docks. The men dug canals and built the walls around the Arsenal. Other convicts were put to work driving in posts to protect the riverbanks from erosion.

The convicts worked long hours on the banks of the Thames and at the dockyards at Woolwich: 10 hours during summer, 7 in the winter.

Convict work

In July 1777 a correspondent from Scots Magazine gave an account of the employment and treatment of the convicts employed in ballast-heaving:

There are upwards of two hundred of them who are employed as follows: Some are sent about a mile below Woolwich in lighters to raise ballast, and to row it back to the embankment at Woolwich Warren, close to the end of the Target Walk: others are there employed in throwing it from the lighters.

Some wheel it to different parts to be sifted: others wheel it from the Skreen, and spread it from the embankment.

A party is continually busied in turning round a machine for driving piles [posts] to secure the embankment from the rapidity of the tides.

Carpenters are employed in repairing the Justitia and Censor hulks, that lie hard by for the nightly reception of those objects, who have fetters on each leg, with a chain between, that ties variously, some round their middle, others upright to the throat. Some are chained two and two; and others, whose crimes have been enormous, with heavy fetters. Six or seven are continually walking about with them with drawn cutlasses, to prevent their escape and likewise prevent idleness.

There are upwards of two hundred of them who are employed as follows: Some are sent about a mile below Woolwich in lighters to raise ballast, and to row it back to the embankment at Woolwich Warren, close to the end of the Target Walk: others are there employed in throwing it from the lighters.

Some wheel it to different parts to be sifted: others wheel it from the Skreen, and spread it from the embankment.

A party is continually busied in turning round a machine for driving piles [posts] to secure the embankment from the rapidity of the tides.

Carpenters are employed in repairing the Justitia and Censor hulks, that lie hard by for the nightly reception of those objects, who have fetters on each leg, with a chain between, that ties variously, some round their middle, others upright to the throat. Some are chained two and two; and others, whose crimes have been enormous, with heavy fetters. Six or seven are continually walking about with them with drawn cutlasses, to prevent their escape and likewise prevent idleness.

The prisoners were chained up at night.

Manacles were used on board prison hulks, Royal Navy vessels and merchantmen to restrain prisoners and crew members. This particular forged steel set, with a screw fastening mechanism

A day in the life.

James Hardy Vaux was a prisoner on the Retribution, an old Spanish vessel, at Woolwich during the early 1800s.

While waiting to be transported for a second time to New South Wales, he recalled:

Every morning, at seven o'clock, all the convicts capable of work, or, in fact, all who are capable of getting into the boats, are taken ashore to the Warren, in which the Royal Arsenal and other public buildings are situated, and there employed at various kinds of labour; some of them very fatiguing; and while so employed, each gang of sixteen or twenty men is watched and directed by a fellow called a guard.

These guards are commonly of the lowest class of human beings; wretches devoid of feeling; ignorant in the extreme, brutal by nature, and rendered tyrannical and cruel by the consciousness of the power they posses..

While waiting to be transported for a second time to New South Wales, he recalled:

Every morning, at seven o'clock, all the convicts capable of work, or, in fact, all who are capable of getting into the boats, are taken ashore to the Warren, in which the Royal Arsenal and other public buildings are situated, and there employed at various kinds of labour; some of them very fatiguing; and while so employed, each gang of sixteen or twenty men is watched and directed by a fellow called a guard.

These guards are commonly of the lowest class of human beings; wretches devoid of feeling; ignorant in the extreme, brutal by nature, and rendered tyrannical and cruel by the consciousness of the power they posses..

Life on board - Appalling conditions

Conditions on board the floating gaols were appalling. The standards of hygiene were so poor that disease spread quickly. The sick were given little medical attention and were not separated from the healthy. Two months after the first convicts had been placed on board the hulks, an epidemic of gaol fever (a form of typhus spread by vermin) spread among them. It persisted on and off for more than three years.

Dysentery, caused by drinking brackish water, was also widespread. At first, patients, whatever their state of health, lay on the bare floor. Later they were given straw mattresses and their irons were removed.

During the first 20 years of their establishment (1776 - 1796), the hulks received around 8000 convicts. Almost one in four of these died on board. Hulk fever, a form of typhus that flourished in dirty, crowded conditions, was rife, as was pulmonary tuberculosis. Most of the deaths on board were caused by neglect. With adequate medical care thousands of lives could have been saved.

Dysentery, caused by drinking brackish water, was also widespread. At first, patients, whatever their state of health, lay on the bare floor. Later they were given straw mattresses and their irons were removed.

During the first 20 years of their establishment (1776 - 1796), the hulks received around 8000 convicts. Almost one in four of these died on board. Hulk fever, a form of typhus that flourished in dirty, crowded conditions, was rife, as was pulmonary tuberculosis. Most of the deaths on board were caused by neglect. With adequate medical care thousands of lives could have been saved.

Death and disease

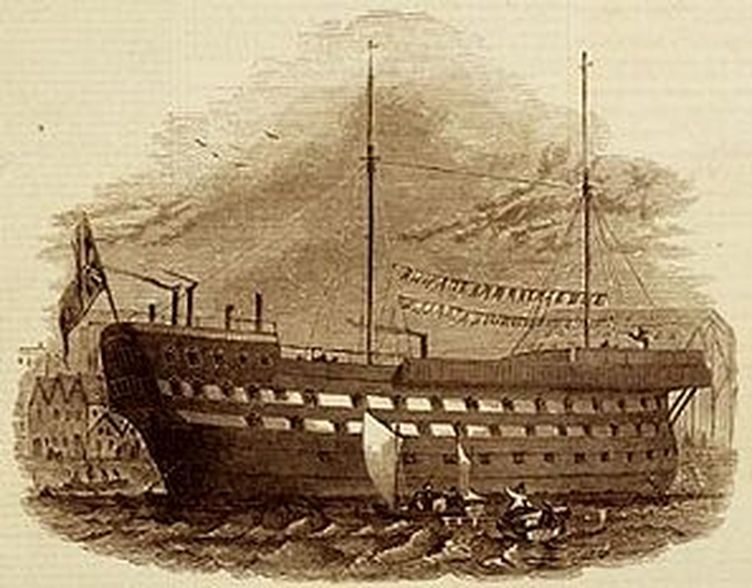

Convict ward on the prison hulk Warrior (1781). Mortality rates of around 30% were quite common. Between 1776 and 1795, nearly 2000 out of almost 6000 convicts serving their sentence on board the hulks died. Many of the convicts sent to New South Wales in the early years were already disease ridden when they left the hulks. As a result, there were serious typhoid and cholera epidemics on many of the vessels heading for Australia

A tough life

The living quarters were very bad. The hulks were cramped and the prisoners slept in fetters. The prisoners had to live on one deck that was barely high enough to let a man stand up. The officers lived in cabins in the stern.

Attempts by any prisoners to file away or knock off the chains around their waists and ankles led to frequent floggings, extra irons and solitary confinement in tiny cells with names like the 'Black Hole'. Floggings with a cat o'nine tails were a common occurrence on board the hulks.

Attempts by any prisoners to file away or knock off the chains around their waists and ankles led to frequent floggings, extra irons and solitary confinement in tiny cells with names like the 'Black Hole'. Floggings with a cat o'nine tails were a common occurrence on board the hulks.

Food on the hulks

The authorities were always keen to keep down the cost of the prisons. They wanted to avoid giving prisoners a better life than the poor had outside the hulks.

The quality of the prisoners' food was therefore kept as low as possible. The monotonous daily meals consisted chiefly of:

The biscuits were often mouldy and green on both sides! On two days a week the meat was replaced by oatmeal and cheese. Each prisoner had two pints of beer four days a week, and badly filtered water, drawn from the river, on the others.

Sometimes, the captain of a hulk would allow the convicts to plant vegetables in plots near the Arsenal. This attempt to add something extra to the poor diet of the prisoners depended on the goodwill, or otherwise, of the individual in charge

The quality of the prisoners' food was therefore kept as low as possible. The monotonous daily meals consisted chiefly of:

- ox-cheek, either boiled or made into soup

- pease

- bread or biscuit.

The biscuits were often mouldy and green on both sides! On two days a week the meat was replaced by oatmeal and cheese. Each prisoner had two pints of beer four days a week, and badly filtered water, drawn from the river, on the others.

Sometimes, the captain of a hulk would allow the convicts to plant vegetables in plots near the Arsenal. This attempt to add something extra to the poor diet of the prisoners depended on the goodwill, or otherwise, of the individual in charge

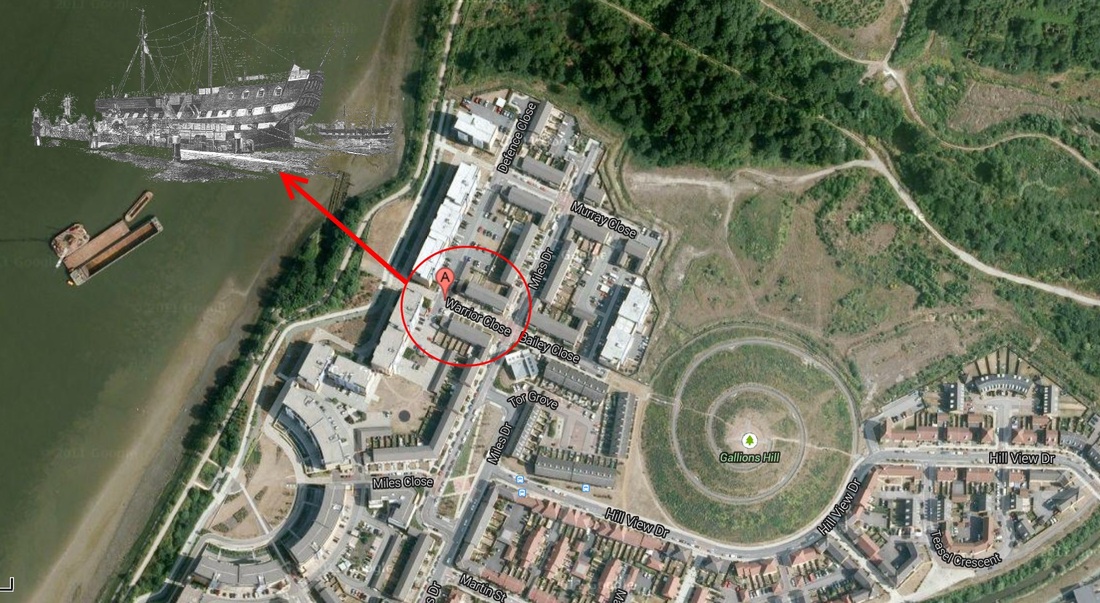

Where was the Warrior Prison ship located?

From the location described and the coincidence of this name given by developers as "Warrior Close" I believe it was just about here but may be wrong.

The convicts' burial grounds

From 1776 until around 1817, the convicts were buried in unmarked graves inside the Warren. Great quantities of human bone were unearthed when the new gun factories were built in the late 1850s. Col Pilkington RE had complained to the War Office before 1817 about the "noxious and distressing" practice of burying convicts in ground that was already full to overflowing. It has been suggested that after 1817 burials took place on the north side of the river, however, this is unlikely. Pilkington investigated the possibility, but the Arsenal's holding of 13 acres on the north bank, used for grazing the Artillery's horses, was sold at auction soon after. It is more likely that the burial site moved to the far end of the Arsenal's land on the south bank, where it continued until the closure of the hulks in 1856. The following contemporary account is taken from "The criminal prisons of London" (Mayhew / Binney):-

Further reading

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Tales from the Woolwich Hulks

The first account is from "Old Convict Days" by William Derricourt. The second, by Roger Hancox, is reprinted from The Midland Ancestor

On the hulk Justitia at Woolwich

After sentence I was condemned, previous to being sent to the hulks, to the treadmill in Stafford Goal. There being no corn to grind and no opposing friction to the weight of the steppers on the wheel, if ever mortal boy walked on the wind I did then. The turns were so rapid that should anyone have missed his footing a broken leg might have been the consequence.

This time came to an end, and orders were received for my being passed on with others to the hulks at Woolwich. Quarters were assigned me on board the Justitia Hulk. Before going on board we were stripped to the skin and scrubbed with a hard scrubbing brush, something like a stiff birch broom, and plenty of soft soap, while the hair was clipped from our heads as close as scissors could go. This scrubbing we endured until we looked like boiled lobsters, and the blood was drawn in many places. We were then supplied with new 'magpie' suits -- one side black or blue and the other side yellow. Our next experience was being marched off to the blacksmith, who riveted on our ankles rings of iron connected by eight links to a ring in the centre, to which was fastened an up and down strap or cord reaching to the waist-belt. This last supported the links, and kept them from dragging on the ground. Then we had what were called knee garters. A strap passing from them to the basils and buckled in front and behind caused the weight of the irons to traverse on the calf of the leg.

In this rig-out we were transferred to the hulk, where we received our numbers, for no names were used. My number was 5418 -- called 'five four eighteen'. I was placed in the boys' ward, top deck No. 24, and as turf-man's gang our first business was repairing the butts, a large mound of earth against which the guns were practiced. After completing this we were employed some days at emptying barges, and then at a rocket-shed in the arsenal cleaning shot, and knocking rust scales from shells, filling them with scrap iron, etc., as great preparations were going on for the China war. At other times we would be moving gun carriages or weeding the long lanes between mounted guns. One particular job I had was cleaning 'Long Tom,' a 21-foot gun at the gate. During all this time I was never for a moment without the leg irons, weighing about twelve pounds, and indeed, so used to them had I become that I actually should have missed them had they been removed. Though our work was constant, we did not fare badly as regards victuals. Our mid-day meal often consisted of broth, beef and potatoes, sometimes of bread or biscuit and cheese and half a pint of ale. One custom of the times was that for each prisoner one penny per week was laid aside by the Government, with the object of securing the workers from the disgrace of being simple slaves. This money, any man, on recovering his freedom, could claim by proving to the proper authorities who he was; but it is hardly necessary to say that, for personal reasons, very few cared to go to this trouble.

At intervals the Chatham smack would come alongside and take a batch of the boys from Woolwich for Chatham. Although I was at the boys' ward, I, being bigger and stronger than the others, was worked in the men s gang, thus escaping being sent to Chatham, where the discipline on the hulks was much more severe than at Woolwich. I became boss of the boys' ward and had to see that the regulations were properly carried out. I had to look to general cleanliness, lashing and stowing hammocks, and the victualling department. In all my time on this hulk my conduct was very good, and on only one occasion did I get into the slightest trouble. This happened in this wise: One of the boys, on my reproving him for neglect and carelessness in regard to this hammock, became obstinate and cheeky, and from words we came to blows. Instead of reporting him, I, then and there, lathered him, was complained of to the captain, and ordered to be flogged. With two others I was taken to the place of punishment, where victims were laid across a small cask, their feet and hands being extended to the utmost, to in this position receive, if boys, a certain number of stripes with a birch rod, or, if men, a certain number with the cat. The sight of the effect of the rod on the first boy's skin positively made my flesh creep; but before my turn came both the captain and Twyman, the guard of the gang, pleaded so strongly for me because of my general good conduct that I was let off.

On board the Justitia Hulk there were about 400 of us, and occasionally the 'Bay ships', or transports, would come up the river to take off drafts from the different hulks. We always knew the transports by the number of soldiers on their decks. The drafts were, of course, for transportation to the various penal colonies.

At the distance of about a mile from our hulk lay the hospital ship, which I only once had the misfortune to visit. While at work one day I was seized with a paralytic stroke, entirely disabling one side, and making me almost speechless. After three days in hospital I nearly recovered the use of my side, also of my voice; but I was kept on board a short time longer, engaged in light duties among the patients.

In the berth next to me was an old man employed in the same way. I once found him in one of the funniest fixes I can ever remember. One day when I was at work in another part of the vessel I lost sight of the old fellow and, upon seeking for him, found that he had actually buried himself. The thing happened in this way: On board, stowed away in one corner, were a number of empty coffins. The day being hot, the old man got into one of these and fell asleep, not knowing that his resting-place had been used to hold pitch. The weather was warm, and the sleeper, when he woke up, found that he had sunk into the remains of the pitch, which still filled about a quarter of the depth of the coffin, and could by no means get out. The coffin had to be knocked to pieces to deliver him, and he received 25 lashes for neglect of duty and idleness.

I only remained in hospital one week and was then returned to the Justitia, where, because of my having suffered from paralysis, and my general good conduct, one of my leg irons was struck off. The feeling of having one leg fettered and the other free was very curious. On one leg was twelve pounds of iron and the other seemed as light as cork, and, do what I would, I could not get them both to act together. I wished over and over again to have my fetters arranged as before, instead of having all the weight on one leg. I actually asked the captain to have this done, but he only laughed at me and told me I should soon get accustomed to the change, as I shortly did.

I want here to particularly mention the Christian treatment of prisoners in England in the hulks as compared with the misery and hardships they had to endure in the colonial depots. The daily practice on board the Justitia was to choose a delegate, as we called him, from each ward, whose duty it was to receive all rations supplied, to inspect them, and refuse all he considered unfit for use, drawing, say, good pork instead of bad beef, or good biscuit instead of bad bread. We were frequently visited by a Church of England clergyman. This good man, before the sailing of any convict ship, would address the various drafts in a way so full of feeling that he often drew tears from his listeners. To the older men he would point out the rewards and blessings of reformation, appealing by sound and earnest counsel to their better feelings, rather than working on their fears. At the same time he did not fail to point out the punishment that would surely follow fresh crimes. To the young he would tell of the many opportunities they would have of securing for themselves the full rights of free citizenship in the land of their forced adoptions, and the chance of their becoming independent by integrity, frugality, industry and perseverance. More than once I heard him say that he hoped those who went across the wide waters would sometimes, whether in prosperity or adversity, have a kindly thought for the old minister who would always have the warmest wishes for their happiness.

Shortly before my turn came to be removed to the transport ship, our kind captain of the Justitia told me that as I had declared my innocence of the crime laid to my charge he had made all inquiries as to the magistrate who had committed me, and as to the captain of the flyboat upon which I had served with the boy who really stole the waistcoat. He had, of course, discovered that the magistrate was, as I have already stated, dead, and that the flyboat man had been executed for the canal murder. The captain of the hulk -- whose name I cannot remember now -- could therefore find out nothing to help me; but with the greatest kindness he told me he would manage to let me have the choice between Bermuda, Botany Bay, and Hobart Town, in Van Dieman's Land. He said thought, if I chose Bermuda, I might get a remission of half sentence, the climate was deadly, and he would advise me to go to Van Dieman's Land, and he would endeavour to make arrangements for me to be kept in Hobart's Town. I thanked him, and assured him I would be ever grateful for his kindness, of which I was soon to have another proof in the treatment accorded me on the voyage.

I have now arrived in my story at the year 1839, when I was about to say good-bye to the old country, with now knowledge when or how I might again set foot in it. On the arrival of our ship, the Asia '5th' -- so called from the voyage on which she was starting being her fifth one to the colonies -- we were ranged on the quarter-deck of the hull, and two smiths freed us from our irons, now endured for nine months. The sensation of having the twelve pounds struck off from one leg was exactly the same as that felt on the taking off of the first iron. Our irons being off we were taken by boats in batches to the Asia, there to be guarded by a detachment of the 96th Regiment.

Previous to our removal the doctor of the Asia came on board the hulk, when the captain, following up on his former acts of kindness, pointed me out to him, said that my conduct had been very good, and that he believed there was in me the making of a good man. this was the means of making my life on the long, weary voyage somewhat more comfortable than it otherwise might have been. On being put on board the Asia there were served to each man his cooking, eating, and drinking utensils, with a small keg for water. We were then told off to the bunks, which held four each. Besides these bunks there were some hammocks, and, through the captain of the Justitia having spoken of me to the doctor, I was given a hammock at the bottom of the hatchway, and soon appointed to a billet. A sailor was sent to show me where the water and pumps stood, and my duty was to fill the men's kegs. Some time after, having made friends with the steward's assistant, he managed to put a bag of biscuits close to a partition, so that, by putting my arm through a chain hole, I could just reach it. My friend filled up the bag again when it got low, so that I was provided with extra bread throughout the voyage.

After arriving at Portsmouth, and just before starting again, the bumboats came alongside, and those who were lucky enough to have any money were allowed to buy. Very few had anything to spend, but I had been careful to save up the little that I had received while at Woolwich. I had in all eight shillings. Part I spent at Portsmouth, and the rest at Teneriffe.

I WAS TAKEN INTO CUESTY - The story of George Reading

George Reading wrote a letter to his brother Mark, which began "I was Taken into Cuesty and Taken To Gaol and thear I remained ..." The letter was in the form of a diary, beginning from the time when he was taken into custody on Saturday 5 February 1841 and continuing until it was posted at "Timones Bay" near the Cape of Good Hope, where he had arrived on Wednesday 29 December on his way as a convict to Van Diemens Land (Tasmania). Mark was my great-great-grandfather.

On Monday 14 February George appeared before the magistrates. His crimes, as reported in the Coventry Standard of 19 February, were that as a letter carrier he had the previous November "stolen from a letter addressed to Miss Masters, dressmaker, High Street, Coventry, two yards of black satin" and also stolen "from a letter sent by Mr Wm Baker, silversmith, of Shrewsbury, to Mr Powell, watchmaker, St John Street ... a five pound Bank of England note". The Coventry Herald and Observer of the same date reported that the black satin "was found by Mr Prosser, Chief Constable, on the 6th of the present month, in a box in Reading's bedroom", and that the £5 note "from being paid into the Coventry & Warwickshire Bank ... was traced back in the clearest possible manner to the possession of Reading, who obtained change or cash for it from Mr Russel, of the Cranes Inn". Since in both cases the articles were traced as having been in the possession of the prisoner, he was committed for trial at the Assizes.

At the Coventry City Assizes on 24 March George Reading was found guilty of "Stealing letters being a servant of the Post Office", and sentenced to transportation for 10 years. His age was recorded as being 44, and his Degree of Instruction as imperfect (Criminal Register, England and Wales 1841, HO 27/65). On Saturday 21 April he was taken from Coventry to a prison hulk at Woolwich, arriving at about half past three in the afternoon, where he says "I was Striped of my Clous and then I was Put into a tub of water and well washed all over and I neaver Saw my Clous after and then I Put on thear dress which was Course brown dress and then I had a hion Put round my leage and that was Fastned on my leage and I weared it day and night and it was Three Pounds and I wared it day and night".

George was set to work in the dockyard, where he "youst To onload and load Shiping of all sorts of Stors Such as Iron and wood and Copper and Stone and bricks and all kinds of things For work". Later, he worked on the building of the 120 gun Royal Navy ship Trafalgar, whose figurehead was Nelson, and which he said was "the largest Ever built at woolwich". George saw the Trafalgar launched on Monday 21 June by queen Victoria, and recorded that "the queen was thear and her attendance and a great many nobles and ladies of all ranks I never Saw So many People togeather in my life". The Times reported the event at great length the following day, beginning "We do not suppose Woolwich ever witnessed so gay a scene as that by which it was yesterday enlivened". It was a very hot day, and the launching was at half past two; the Times reported that soon afterwards "the rain which had kept off, as if in expectation of the event, began to descend in torrents"

George lived on the prison hulk Warrior, which held up to 800 prisoners, and was entered as a "Convict labourer" in the 1841 census. The Quarterly return of Prisoners for 1 April to 30 June 1841 (HO 8/68) listed 757 prisoners, including George Reading who was number 962 on the ship's book. The surgeon's report showed him to be "Healthy", and his behaviour during the quarter was reported as being "Good"; the report was signed by Richard Armstrong, Overseer of the Warrior, on 8 July 1841. The Letter Book for the prison hulks Ganymede and Warrior for the period 1837 to 1844 (HO 9/12) reported that George Reding's character was "Bad", but this seems to be at variance with George's own comment that "the hulk that I was in was Veary Clean and Veary holsom and thear was a Veary large Chappel in the Ship ... and I youst to go Twis in a week".

George was taken from Woolwich on Saturday 21 August to Chatham, and put on board the Tortoise on which he would be transported to Van Diemens Land. They sailed firstly to Sheerness and then on to Portsmouth which they reached on Friday 27 August, and where the ship's surgeon Thos Brownrigg reported in his log book (ADM 101/71/8) that some prisoners had to be transferred to a convict hospital ship, and then on to Plymouth where some prisoners were transferred to the convict ship Stirling Castle. The Tortoise weighed anchor and set out for Van Diemens Land at four o'clock on Sunday 3 October, but George recorded that they "went through the English and Irish Channel Till we Came to the bay of bisey and then the Gentlemen on bord thought it was not Safe and we Came back again". After making some repairs and transferring more prisoners to the Stirling Castle, they set off again on Tuesday 26 October, again facing bad weather until they were off the coast of Africa.

Life for the four hundred men on the convict ship does not seem to have been too hard. George says that after three days "I had my iron Taken of my leage ... and I Veary Glad as it was Veary Great Easment to my mind". The weather for most of the voyage was very hot, and he wrote that "I do not wear nothing but my Sheart and Trousers and Shues". Near the equator he wrote that "I heave not Sleap on my bed for 4 weeks and the men Sleep in all directions on the deck ... I my Sealf Sleep on the deck with my blanket under me". The normal sleeping arrangement was in bunks, with four men to one bunk which was seven feet square. To provide fresh air in the crowded quarters there were three air pumps which had to be hand operated day and night. George seems to have had some responsibility for these pumps, and wrote "and I have to look over twenty men to See as thea due thear little work and I never Sile my hands for any thing"

The journey had its interests. George reports having seen porpoises, dolphins, and flying fish, and also wrote that "we have had a howell Come to hus and the Saiolers Caut it and I had it in my hands ... and thea killed it and Stuffed it". However, it also had its dangers, and he reports that "the men Drink a great deal of Vinegar to keep the Scurvy away and I due not drink it my Sealf but I rub my temples with it". He also wrote how "wone of hour Prisnors died and he was buread in the afternoon and he was buread in the deep"; the ship's surgeon reported in his log that three prisoners died during the voyage.

George's letter was posted in South Africa. He said that he "rote to my Poor dear unfortunate wife", and ends by saying to his brother "and I have sent wone to you all as you may keep it for my sake and God bless you all till you hear from me again". The family did keep it, but as far as I know he did not write again.

On the hulk Justitia at Woolwich

After sentence I was condemned, previous to being sent to the hulks, to the treadmill in Stafford Goal. There being no corn to grind and no opposing friction to the weight of the steppers on the wheel, if ever mortal boy walked on the wind I did then. The turns were so rapid that should anyone have missed his footing a broken leg might have been the consequence.

This time came to an end, and orders were received for my being passed on with others to the hulks at Woolwich. Quarters were assigned me on board the Justitia Hulk. Before going on board we were stripped to the skin and scrubbed with a hard scrubbing brush, something like a stiff birch broom, and plenty of soft soap, while the hair was clipped from our heads as close as scissors could go. This scrubbing we endured until we looked like boiled lobsters, and the blood was drawn in many places. We were then supplied with new 'magpie' suits -- one side black or blue and the other side yellow. Our next experience was being marched off to the blacksmith, who riveted on our ankles rings of iron connected by eight links to a ring in the centre, to which was fastened an up and down strap or cord reaching to the waist-belt. This last supported the links, and kept them from dragging on the ground. Then we had what were called knee garters. A strap passing from them to the basils and buckled in front and behind caused the weight of the irons to traverse on the calf of the leg.

In this rig-out we were transferred to the hulk, where we received our numbers, for no names were used. My number was 5418 -- called 'five four eighteen'. I was placed in the boys' ward, top deck No. 24, and as turf-man's gang our first business was repairing the butts, a large mound of earth against which the guns were practiced. After completing this we were employed some days at emptying barges, and then at a rocket-shed in the arsenal cleaning shot, and knocking rust scales from shells, filling them with scrap iron, etc., as great preparations were going on for the China war. At other times we would be moving gun carriages or weeding the long lanes between mounted guns. One particular job I had was cleaning 'Long Tom,' a 21-foot gun at the gate. During all this time I was never for a moment without the leg irons, weighing about twelve pounds, and indeed, so used to them had I become that I actually should have missed them had they been removed. Though our work was constant, we did not fare badly as regards victuals. Our mid-day meal often consisted of broth, beef and potatoes, sometimes of bread or biscuit and cheese and half a pint of ale. One custom of the times was that for each prisoner one penny per week was laid aside by the Government, with the object of securing the workers from the disgrace of being simple slaves. This money, any man, on recovering his freedom, could claim by proving to the proper authorities who he was; but it is hardly necessary to say that, for personal reasons, very few cared to go to this trouble.

At intervals the Chatham smack would come alongside and take a batch of the boys from Woolwich for Chatham. Although I was at the boys' ward, I, being bigger and stronger than the others, was worked in the men s gang, thus escaping being sent to Chatham, where the discipline on the hulks was much more severe than at Woolwich. I became boss of the boys' ward and had to see that the regulations were properly carried out. I had to look to general cleanliness, lashing and stowing hammocks, and the victualling department. In all my time on this hulk my conduct was very good, and on only one occasion did I get into the slightest trouble. This happened in this wise: One of the boys, on my reproving him for neglect and carelessness in regard to this hammock, became obstinate and cheeky, and from words we came to blows. Instead of reporting him, I, then and there, lathered him, was complained of to the captain, and ordered to be flogged. With two others I was taken to the place of punishment, where victims were laid across a small cask, their feet and hands being extended to the utmost, to in this position receive, if boys, a certain number of stripes with a birch rod, or, if men, a certain number with the cat. The sight of the effect of the rod on the first boy's skin positively made my flesh creep; but before my turn came both the captain and Twyman, the guard of the gang, pleaded so strongly for me because of my general good conduct that I was let off.

On board the Justitia Hulk there were about 400 of us, and occasionally the 'Bay ships', or transports, would come up the river to take off drafts from the different hulks. We always knew the transports by the number of soldiers on their decks. The drafts were, of course, for transportation to the various penal colonies.

At the distance of about a mile from our hulk lay the hospital ship, which I only once had the misfortune to visit. While at work one day I was seized with a paralytic stroke, entirely disabling one side, and making me almost speechless. After three days in hospital I nearly recovered the use of my side, also of my voice; but I was kept on board a short time longer, engaged in light duties among the patients.

In the berth next to me was an old man employed in the same way. I once found him in one of the funniest fixes I can ever remember. One day when I was at work in another part of the vessel I lost sight of the old fellow and, upon seeking for him, found that he had actually buried himself. The thing happened in this way: On board, stowed away in one corner, were a number of empty coffins. The day being hot, the old man got into one of these and fell asleep, not knowing that his resting-place had been used to hold pitch. The weather was warm, and the sleeper, when he woke up, found that he had sunk into the remains of the pitch, which still filled about a quarter of the depth of the coffin, and could by no means get out. The coffin had to be knocked to pieces to deliver him, and he received 25 lashes for neglect of duty and idleness.

I only remained in hospital one week and was then returned to the Justitia, where, because of my having suffered from paralysis, and my general good conduct, one of my leg irons was struck off. The feeling of having one leg fettered and the other free was very curious. On one leg was twelve pounds of iron and the other seemed as light as cork, and, do what I would, I could not get them both to act together. I wished over and over again to have my fetters arranged as before, instead of having all the weight on one leg. I actually asked the captain to have this done, but he only laughed at me and told me I should soon get accustomed to the change, as I shortly did.

I want here to particularly mention the Christian treatment of prisoners in England in the hulks as compared with the misery and hardships they had to endure in the colonial depots. The daily practice on board the Justitia was to choose a delegate, as we called him, from each ward, whose duty it was to receive all rations supplied, to inspect them, and refuse all he considered unfit for use, drawing, say, good pork instead of bad beef, or good biscuit instead of bad bread. We were frequently visited by a Church of England clergyman. This good man, before the sailing of any convict ship, would address the various drafts in a way so full of feeling that he often drew tears from his listeners. To the older men he would point out the rewards and blessings of reformation, appealing by sound and earnest counsel to their better feelings, rather than working on their fears. At the same time he did not fail to point out the punishment that would surely follow fresh crimes. To the young he would tell of the many opportunities they would have of securing for themselves the full rights of free citizenship in the land of their forced adoptions, and the chance of their becoming independent by integrity, frugality, industry and perseverance. More than once I heard him say that he hoped those who went across the wide waters would sometimes, whether in prosperity or adversity, have a kindly thought for the old minister who would always have the warmest wishes for their happiness.

Shortly before my turn came to be removed to the transport ship, our kind captain of the Justitia told me that as I had declared my innocence of the crime laid to my charge he had made all inquiries as to the magistrate who had committed me, and as to the captain of the flyboat upon which I had served with the boy who really stole the waistcoat. He had, of course, discovered that the magistrate was, as I have already stated, dead, and that the flyboat man had been executed for the canal murder. The captain of the hulk -- whose name I cannot remember now -- could therefore find out nothing to help me; but with the greatest kindness he told me he would manage to let me have the choice between Bermuda, Botany Bay, and Hobart Town, in Van Dieman's Land. He said thought, if I chose Bermuda, I might get a remission of half sentence, the climate was deadly, and he would advise me to go to Van Dieman's Land, and he would endeavour to make arrangements for me to be kept in Hobart's Town. I thanked him, and assured him I would be ever grateful for his kindness, of which I was soon to have another proof in the treatment accorded me on the voyage.

I have now arrived in my story at the year 1839, when I was about to say good-bye to the old country, with now knowledge when or how I might again set foot in it. On the arrival of our ship, the Asia '5th' -- so called from the voyage on which she was starting being her fifth one to the colonies -- we were ranged on the quarter-deck of the hull, and two smiths freed us from our irons, now endured for nine months. The sensation of having the twelve pounds struck off from one leg was exactly the same as that felt on the taking off of the first iron. Our irons being off we were taken by boats in batches to the Asia, there to be guarded by a detachment of the 96th Regiment.

Previous to our removal the doctor of the Asia came on board the hulk, when the captain, following up on his former acts of kindness, pointed me out to him, said that my conduct had been very good, and that he believed there was in me the making of a good man. this was the means of making my life on the long, weary voyage somewhat more comfortable than it otherwise might have been. On being put on board the Asia there were served to each man his cooking, eating, and drinking utensils, with a small keg for water. We were then told off to the bunks, which held four each. Besides these bunks there were some hammocks, and, through the captain of the Justitia having spoken of me to the doctor, I was given a hammock at the bottom of the hatchway, and soon appointed to a billet. A sailor was sent to show me where the water and pumps stood, and my duty was to fill the men's kegs. Some time after, having made friends with the steward's assistant, he managed to put a bag of biscuits close to a partition, so that, by putting my arm through a chain hole, I could just reach it. My friend filled up the bag again when it got low, so that I was provided with extra bread throughout the voyage.

After arriving at Portsmouth, and just before starting again, the bumboats came alongside, and those who were lucky enough to have any money were allowed to buy. Very few had anything to spend, but I had been careful to save up the little that I had received while at Woolwich. I had in all eight shillings. Part I spent at Portsmouth, and the rest at Teneriffe.

I WAS TAKEN INTO CUESTY - The story of George Reading

George Reading wrote a letter to his brother Mark, which began "I was Taken into Cuesty and Taken To Gaol and thear I remained ..." The letter was in the form of a diary, beginning from the time when he was taken into custody on Saturday 5 February 1841 and continuing until it was posted at "Timones Bay" near the Cape of Good Hope, where he had arrived on Wednesday 29 December on his way as a convict to Van Diemens Land (Tasmania). Mark was my great-great-grandfather.

On Monday 14 February George appeared before the magistrates. His crimes, as reported in the Coventry Standard of 19 February, were that as a letter carrier he had the previous November "stolen from a letter addressed to Miss Masters, dressmaker, High Street, Coventry, two yards of black satin" and also stolen "from a letter sent by Mr Wm Baker, silversmith, of Shrewsbury, to Mr Powell, watchmaker, St John Street ... a five pound Bank of England note". The Coventry Herald and Observer of the same date reported that the black satin "was found by Mr Prosser, Chief Constable, on the 6th of the present month, in a box in Reading's bedroom", and that the £5 note "from being paid into the Coventry & Warwickshire Bank ... was traced back in the clearest possible manner to the possession of Reading, who obtained change or cash for it from Mr Russel, of the Cranes Inn". Since in both cases the articles were traced as having been in the possession of the prisoner, he was committed for trial at the Assizes.

At the Coventry City Assizes on 24 March George Reading was found guilty of "Stealing letters being a servant of the Post Office", and sentenced to transportation for 10 years. His age was recorded as being 44, and his Degree of Instruction as imperfect (Criminal Register, England and Wales 1841, HO 27/65). On Saturday 21 April he was taken from Coventry to a prison hulk at Woolwich, arriving at about half past three in the afternoon, where he says "I was Striped of my Clous and then I was Put into a tub of water and well washed all over and I neaver Saw my Clous after and then I Put on thear dress which was Course brown dress and then I had a hion Put round my leage and that was Fastned on my leage and I weared it day and night and it was Three Pounds and I wared it day and night".

George was set to work in the dockyard, where he "youst To onload and load Shiping of all sorts of Stors Such as Iron and wood and Copper and Stone and bricks and all kinds of things For work". Later, he worked on the building of the 120 gun Royal Navy ship Trafalgar, whose figurehead was Nelson, and which he said was "the largest Ever built at woolwich". George saw the Trafalgar launched on Monday 21 June by queen Victoria, and recorded that "the queen was thear and her attendance and a great many nobles and ladies of all ranks I never Saw So many People togeather in my life". The Times reported the event at great length the following day, beginning "We do not suppose Woolwich ever witnessed so gay a scene as that by which it was yesterday enlivened". It was a very hot day, and the launching was at half past two; the Times reported that soon afterwards "the rain which had kept off, as if in expectation of the event, began to descend in torrents"

George lived on the prison hulk Warrior, which held up to 800 prisoners, and was entered as a "Convict labourer" in the 1841 census. The Quarterly return of Prisoners for 1 April to 30 June 1841 (HO 8/68) listed 757 prisoners, including George Reading who was number 962 on the ship's book. The surgeon's report showed him to be "Healthy", and his behaviour during the quarter was reported as being "Good"; the report was signed by Richard Armstrong, Overseer of the Warrior, on 8 July 1841. The Letter Book for the prison hulks Ganymede and Warrior for the period 1837 to 1844 (HO 9/12) reported that George Reding's character was "Bad", but this seems to be at variance with George's own comment that "the hulk that I was in was Veary Clean and Veary holsom and thear was a Veary large Chappel in the Ship ... and I youst to go Twis in a week".

George was taken from Woolwich on Saturday 21 August to Chatham, and put on board the Tortoise on which he would be transported to Van Diemens Land. They sailed firstly to Sheerness and then on to Portsmouth which they reached on Friday 27 August, and where the ship's surgeon Thos Brownrigg reported in his log book (ADM 101/71/8) that some prisoners had to be transferred to a convict hospital ship, and then on to Plymouth where some prisoners were transferred to the convict ship Stirling Castle. The Tortoise weighed anchor and set out for Van Diemens Land at four o'clock on Sunday 3 October, but George recorded that they "went through the English and Irish Channel Till we Came to the bay of bisey and then the Gentlemen on bord thought it was not Safe and we Came back again". After making some repairs and transferring more prisoners to the Stirling Castle, they set off again on Tuesday 26 October, again facing bad weather until they were off the coast of Africa.

Life for the four hundred men on the convict ship does not seem to have been too hard. George says that after three days "I had my iron Taken of my leage ... and I Veary Glad as it was Veary Great Easment to my mind". The weather for most of the voyage was very hot, and he wrote that "I do not wear nothing but my Sheart and Trousers and Shues". Near the equator he wrote that "I heave not Sleap on my bed for 4 weeks and the men Sleep in all directions on the deck ... I my Sealf Sleep on the deck with my blanket under me". The normal sleeping arrangement was in bunks, with four men to one bunk which was seven feet square. To provide fresh air in the crowded quarters there were three air pumps which had to be hand operated day and night. George seems to have had some responsibility for these pumps, and wrote "and I have to look over twenty men to See as thea due thear little work and I never Sile my hands for any thing"

The journey had its interests. George reports having seen porpoises, dolphins, and flying fish, and also wrote that "we have had a howell Come to hus and the Saiolers Caut it and I had it in my hands ... and thea killed it and Stuffed it". However, it also had its dangers, and he reports that "the men Drink a great deal of Vinegar to keep the Scurvy away and I due not drink it my Sealf but I rub my temples with it". He also wrote how "wone of hour Prisnors died and he was buread in the afternoon and he was buread in the deep"; the ship's surgeon reported in his log that three prisoners died during the voyage.

George's letter was posted in South Africa. He said that he "rote to my Poor dear unfortunate wife", and ends by saying to his brother "and I have sent wone to you all as you may keep it for my sake and God bless you all till you hear from me again". The family did keep it, but as far as I know he did not write again.

Information from Hugh Gladden, his grandfather worked in the Royal Arsenal.

THALIA FLOATING MAGAZINE AT WOOLWICH ARSENAL

My Grandfather Fred Gladden joined the Metropolitan Police in 1890, and from then until his retirement in 1920 he served as a constable with Woolwich Dockyard Division, which at that time was responsible for policing Woolwich Arsenal and Woolwich Dockyard. My father was born in 1904, by which time the family were living at 21 Police Quarters, at Crossness. Dad attended Crossness Primary School (in the grounds of the Outfall Works) and then St. Augustine’s in Belvedere.

Dad told me that one of his father’s duties was to row out to an old ‘powder hulk’ moored in the Thames, to check on security and so forth. The kids would sit on the riverbank and wait for him to return. Dad reckoned his father and his colleagues would sit around on board the hulk, smoking their pipes! He also told me that the only illumination allowed on board was from candles – which seems insane until you realise that if you knock over a candle it tends to go out, whereas an oil-lamp might break and start a fire? Nevertheless, the thought of them smoking pipes on board a ship capable of storing 900 tons of explosives is a bit scary! There would have been a few broken windows in Woolwich if she’d gone up. Perhaps my Dad was pulling my leg.

When I started doing some family research, I found that the powder hulk was ex-HMS Thalia, an old warship. This is what I have found out about her:

‘Thalia’ was a Juno class corvette and was the last ship to be completed at Woolwich Dockyard before that became merely a stores depot (I believe that her hull was built at Deptford Dockyard before it was closed). She was a fully-rigged ‘transition period’ ship with a wooden hull and steam-powered screw propulsion to augment her sails. She was commissioned into the Royal Navy in 1869 or 1871 (accounts vary) and spent the next twenty-odd years of service sailing to China, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, among other places – including, in 1886, Tristan da Cunha. She was decommissioned in 1891, had her engine and rigging removed and was converted to a powder hulk. This much seems to be generally agreed.

However, there is an assertion repeated on several internet ‘naval history’ websites that after the end of her service with the Royal Navy, Thalia was moored at Portsmouth as a powder-hulk: my research suggests that this is a mistake. I suggest that it may be a case of serial copying of an error, its repetition perhaps due to a tendency for some website authors to repeat perceived ‘facts’, without checking sources sufficiently.

I suggest that the evidence that follows shows beyond any reasonable doubt that her days as a powder-hulk were spent, not in Portsmouth, but in the service of Woolwich Royal Arsenal, moored at Tripcock Reach, adjacent to the then Cannon Cartridge Factory.

In roughly chronological order:

1.

There are several references to Thalia in Brigadier O.F.G. Hogg’s ‘The Royal Arsenal: its Background, Origin and History’ (Oxford University Press, London, 1963). Hogg records (volume 2, page 891) the findings of the Sandhurst Committee in 1895, which included the recommendation that ‘Thalia floating magazine, if continued, to be placed in a safer position’. Elsewhere, (page 931) he records the Committee’s observation that “The position of this magazine which has a capacity of 18,000 barrels (900 tons), and which actually contained at the time of the Committee’s enquiry 300 tons of powder in barrels and in cannon cartridges, is, in the opinion of the Committee, one to justify anxiety. The evil seems to be seriously aggravated by the proximity of the magazine to the Cannon Cartridge Establishment, the two being a mutual menace”.

2.

There is a record in the archives of the Peninsular and Orient Steamship Line (‘P&O’) that specifically names the Thalia as a powder hulk that was in collision with a P&O passenger ship near Tripcock Point on January 23rd, 1896. Under the entry for S.S. Shannon, it reads: 23.01.1896: In collision with the powder hulk Thalia off Royal Albert Dock,

London but without significant damage. Thalia was reported to have broken her moorings and ran aground above Tripcock Point.

To account for Thalia’s reported position at the time of the collision it must be assumed that her moorings were broken on the rising tide and that she then drifted upstream on the flood, where she collided with the SS Shannon, outward bound for Bombay (Mumbai), off the entrance to The Royal Albert Dock. Fortunately, there was no damage and the Thalia didn’t explode. It seems that on the ebb tide she drifted back downstream and obligingly grounded herself at Tripcock Point. By that time, I believe she had been a powder hulk on the Thames for five years.

3.

In the volume mentioned above in item 1, Hogg goes on to report (pages 931 – 932) that in 1901 three named senior officers at The Royal Arsenal commented “We consider the Thalia floating magazine a great source of danger. Twice her mooring chains have been broken by passing vessels and part of her rail has been carried away. Vessels with smoking funnels pass quite close to her. The Thalia should be disused at once and the use of floating magazines discontinued.”

4.

Hogg also records (page 924) that in 1902, 315 acres of land was purchased ‘for the storage of explosives in place of the floating magazine Thalia’. This entry suggests that Thalia then ‘disappeared from the Woolwich scene’: this may be an assumption of good intention rather than a record of events, as points 5 and 6 that follow here should make clear.

5.

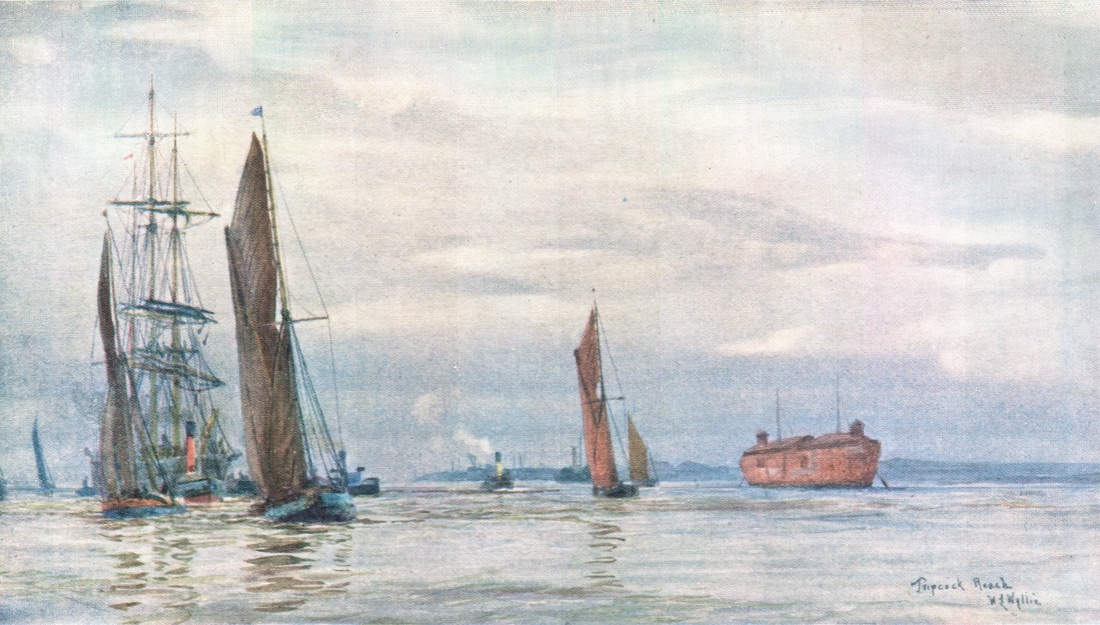

In 1905, the maritime painter William Lionel Wyllie published a book in collaboration with his wife Marion, called London to The Nore (A. & C. Black, London). It was an account of their journey by Thames sailing barge from Westminster to Rochester. Marion wrote the text and William illustrated the book with many watercolours, one of which he called ‘Tripcock Reach’. It is listed on the contents page and captioned as ‘Tripcock’s Reach – the old Powder-hulk “Thalia” ‘. Marion wrote (page 92) “…..we tack and make a board towards the powder-hulk, once H.M. Armed Storeship Thalia.” (She goes on to recount a story about Thalia’s failure to perform sail-drills to the satisfaction of the Admiral while serving in the Mediterranean and her subsequent exclusion from Fleet sail-drills.) Curiously, Marion makes no mention of the dates of their voyage, but I assume it was probably the year before publication, in other words 1904.

6.

In 1907, on July 12th, The London Gazette published some regulations governing the movement of shipping on the Thames, in which Thalia is named: “No steam vessel shall be worked, navigated or placed upon or anchored or moored in the river within three hundred and sixty feet of His Majesty's dock-yard or arsenal at Woolwich or of His Majesty's victualling yard at Deptford except steam vessels belonging to or employed in the service of His Majesty, his heirs or successors and no vessel shall be anchored in the river within a similar distance of His Majesty's powder hulk " Thalia " except for the purpose of loading or discharging explosives out of or into such powder hulk.” (Paragraph number 50)

The same notice, with only very minor variations to the text (e.g. ‘the powder hulk ''Thalia" belonging to Her Majesty lying off the said arsenal’), had also been posted in The London Gazette in April 1897 (page 1959, para 12) and appeared once more in November 1911 (page 8070, para 51).

On the basis of the above evidence therefore, it is possible with a high degree of confidence to place Thalia in the vicinity of Tripcock Reach as a floating magazine in 1895, in 1896, in 1897, in 1901, in 1902, in 1904, in 1907 and in 1911. I have not been able to find any credible evidence to place her at Portsmouth at any date whatsoever. There are however references to a previous HMS Thalia that was apparently hulked at Portsmouth in 1855, where she is said to have served as a Roman Catholic chapel ship until broken up at Cowes in 1867: perhaps that is the source of the confusion?

Nevertheless, there is a period of just over three years between the last 1911 London Gazette notice and the Colledge entry for 1915 (see below) that is as yet unaccounted for: in theory, Thalia could have been transferred to Portsmouth during that time, although that might seem unlikely.

There are references in Naval Service records and War Graves inscriptions to a ship named Thalia based at Cromarty during WW1. One website cites an entry which it claims to be from a book called British Warships 1914-1919, by F.J.Dittmar & J.J.Colledge. It reads: “THALIA, harbour service, store hulk, Cromarty; base ship 2.15 (ex-wooden screw corvette, Juno-class), built 1869, 2240 tons. Sold 16.9.20.”. The current edition of ‘Ships of the Royal Navy, by J.J.Colledge & Ben Warlow, (Casemate, 2010), also records Thalia as being commissioned as a ‘base ship’ in February 1915, and then sold to Rose Street Foundry in Inverness in September 1920, although it makes no reference to where she served as a base ship. Neither entry states why Rose Street Foundry bought her, although it has been assumed that it was for breaking.

Elsewhere, it is claimed that this Thalia was the ‘mothership’ for Area IV of the Auxiliary Patrol anti-submarine and mine-sweeping service for the Cromarty Firth, which was established between December 1914 and August 1915.

I believe that J.J.Colledge is generally regarded as a reliable authority on such matters and that the books he authored are standard reference works for naval historians. It seems likely therefore that there was a base ship at Cromarty called Thalia, and her proposed fate in Inverness, twenty miles or so distant from Cromarty is therefore at least plausible. I have however three concerns with the Cromarty scenario as an account of the fate of the ‘Woolwich Thalia’:

First, assuming that they are the same ship, it seems extraordinary that it was considered worth the expense and considerable risk to tow such a venerable hulk (she would have been over 40 years old at the time) about 600 miles from Woolwich to Cromarty, through the North Sea, with WW1 having already begun (there was no need for such a ‘mothership’ until the Auxiliary Patrols were formed in 1915, so it would seem unlikely that she would have been moved to Cromarty before then). Were suitable candidates for base-ships really so hard to come by in the Cromarty Firth?

Second, I can find no reference to Rose Street Foundry being engaged in ship-breaking activities in Inverness. It seems at least part of their business was as marine engineers and there are accounts of their involvement in repairing coasters and fishing vessels, but I have found no mention of them being involved in ship-breaking or scrap activities.

Third, if the ship in question was the Thalia previously at Woolwich, one has to ask what Rose Street Foundry - who were engineers in metal - would want with the hull of a large wooden ship. It is possible that, like Cutty Sark (built at around the same time), Thalia was of composite construction with iron frames, and with external copper or Muntz metal sheathing beneath the waterline. If so, it might have been financially worthwhile to buy her and to tow her the twenty miles to Inverness for breaking. Unfortunately, I have not been able to discover any details of the precise method used in the construction of HMS Thalia so I cannot say with any confidence that she was of composite construction. Nor do I know the relative value at the time of wrought iron frames, or of Muntz metal, or the costs of towage and breaking, or indeed what was paid for the hulk - so I cannot make any informed judgement of the economic case, although it might seem an improbable way for Rose Street Foundry to make a profit.

On the other hand, neither have I been able to find any evidence on which to base an alternative account of her fate, so it remains theoretically possible that she was towed to Cromarty for use as a Base Ship and that she was eventually scrapped in Inverness.

Dad told me that one of his father’s duties was to row out to an old ‘powder hulk’ moored in the Thames, to check on security and so forth. The kids would sit on the riverbank and wait for him to return. Dad reckoned his father and his colleagues would sit around on board the hulk, smoking their pipes! He also told me that the only illumination allowed on board was from candles – which seems insane until you realise that if you knock over a candle it tends to go out, whereas an oil-lamp might break and start a fire? Nevertheless, the thought of them smoking pipes on board a ship capable of storing 900 tons of explosives is a bit scary! There would have been a few broken windows in Woolwich if she’d gone up. Perhaps my Dad was pulling my leg.

When I started doing some family research, I found that the powder hulk was ex-HMS Thalia, an old warship. This is what I have found out about her:

‘Thalia’ was a Juno class corvette and was the last ship to be completed at Woolwich Dockyard before that became merely a stores depot (I believe that her hull was built at Deptford Dockyard before it was closed). She was a fully-rigged ‘transition period’ ship with a wooden hull and steam-powered screw propulsion to augment her sails. She was commissioned into the Royal Navy in 1869 or 1871 (accounts vary) and spent the next twenty-odd years of service sailing to China, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, among other places – including, in 1886, Tristan da Cunha. She was decommissioned in 1891, had her engine and rigging removed and was converted to a powder hulk. This much seems to be generally agreed.

However, there is an assertion repeated on several internet ‘naval history’ websites that after the end of her service with the Royal Navy, Thalia was moored at Portsmouth as a powder-hulk: my research suggests that this is a mistake. I suggest that it may be a case of serial copying of an error, its repetition perhaps due to a tendency for some website authors to repeat perceived ‘facts’, without checking sources sufficiently.

I suggest that the evidence that follows shows beyond any reasonable doubt that her days as a powder-hulk were spent, not in Portsmouth, but in the service of Woolwich Royal Arsenal, moored at Tripcock Reach, adjacent to the then Cannon Cartridge Factory.

In roughly chronological order:

1.

There are several references to Thalia in Brigadier O.F.G. Hogg’s ‘The Royal Arsenal: its Background, Origin and History’ (Oxford University Press, London, 1963). Hogg records (volume 2, page 891) the findings of the Sandhurst Committee in 1895, which included the recommendation that ‘Thalia floating magazine, if continued, to be placed in a safer position’. Elsewhere, (page 931) he records the Committee’s observation that “The position of this magazine which has a capacity of 18,000 barrels (900 tons), and which actually contained at the time of the Committee’s enquiry 300 tons of powder in barrels and in cannon cartridges, is, in the opinion of the Committee, one to justify anxiety. The evil seems to be seriously aggravated by the proximity of the magazine to the Cannon Cartridge Establishment, the two being a mutual menace”.

2.

There is a record in the archives of the Peninsular and Orient Steamship Line (‘P&O’) that specifically names the Thalia as a powder hulk that was in collision with a P&O passenger ship near Tripcock Point on January 23rd, 1896. Under the entry for S.S. Shannon, it reads: 23.01.1896: In collision with the powder hulk Thalia off Royal Albert Dock,

London but without significant damage. Thalia was reported to have broken her moorings and ran aground above Tripcock Point.

To account for Thalia’s reported position at the time of the collision it must be assumed that her moorings were broken on the rising tide and that she then drifted upstream on the flood, where she collided with the SS Shannon, outward bound for Bombay (Mumbai), off the entrance to The Royal Albert Dock. Fortunately, there was no damage and the Thalia didn’t explode. It seems that on the ebb tide she drifted back downstream and obligingly grounded herself at Tripcock Point. By that time, I believe she had been a powder hulk on the Thames for five years.

3.

In the volume mentioned above in item 1, Hogg goes on to report (pages 931 – 932) that in 1901 three named senior officers at The Royal Arsenal commented “We consider the Thalia floating magazine a great source of danger. Twice her mooring chains have been broken by passing vessels and part of her rail has been carried away. Vessels with smoking funnels pass quite close to her. The Thalia should be disused at once and the use of floating magazines discontinued.”

4.

Hogg also records (page 924) that in 1902, 315 acres of land was purchased ‘for the storage of explosives in place of the floating magazine Thalia’. This entry suggests that Thalia then ‘disappeared from the Woolwich scene’: this may be an assumption of good intention rather than a record of events, as points 5 and 6 that follow here should make clear.

5.

In 1905, the maritime painter William Lionel Wyllie published a book in collaboration with his wife Marion, called London to The Nore (A. & C. Black, London). It was an account of their journey by Thames sailing barge from Westminster to Rochester. Marion wrote the text and William illustrated the book with many watercolours, one of which he called ‘Tripcock Reach’. It is listed on the contents page and captioned as ‘Tripcock’s Reach – the old Powder-hulk “Thalia” ‘. Marion wrote (page 92) “…..we tack and make a board towards the powder-hulk, once H.M. Armed Storeship Thalia.” (She goes on to recount a story about Thalia’s failure to perform sail-drills to the satisfaction of the Admiral while serving in the Mediterranean and her subsequent exclusion from Fleet sail-drills.) Curiously, Marion makes no mention of the dates of their voyage, but I assume it was probably the year before publication, in other words 1904.

6.

In 1907, on July 12th, The London Gazette published some regulations governing the movement of shipping on the Thames, in which Thalia is named: “No steam vessel shall be worked, navigated or placed upon or anchored or moored in the river within three hundred and sixty feet of His Majesty's dock-yard or arsenal at Woolwich or of His Majesty's victualling yard at Deptford except steam vessels belonging to or employed in the service of His Majesty, his heirs or successors and no vessel shall be anchored in the river within a similar distance of His Majesty's powder hulk " Thalia " except for the purpose of loading or discharging explosives out of or into such powder hulk.” (Paragraph number 50)

The same notice, with only very minor variations to the text (e.g. ‘the powder hulk ''Thalia" belonging to Her Majesty lying off the said arsenal’), had also been posted in The London Gazette in April 1897 (page 1959, para 12) and appeared once more in November 1911 (page 8070, para 51).

On the basis of the above evidence therefore, it is possible with a high degree of confidence to place Thalia in the vicinity of Tripcock Reach as a floating magazine in 1895, in 1896, in 1897, in 1901, in 1902, in 1904, in 1907 and in 1911. I have not been able to find any credible evidence to place her at Portsmouth at any date whatsoever. There are however references to a previous HMS Thalia that was apparently hulked at Portsmouth in 1855, where she is said to have served as a Roman Catholic chapel ship until broken up at Cowes in 1867: perhaps that is the source of the confusion?

Nevertheless, there is a period of just over three years between the last 1911 London Gazette notice and the Colledge entry for 1915 (see below) that is as yet unaccounted for: in theory, Thalia could have been transferred to Portsmouth during that time, although that might seem unlikely.

There are references in Naval Service records and War Graves inscriptions to a ship named Thalia based at Cromarty during WW1. One website cites an entry which it claims to be from a book called British Warships 1914-1919, by F.J.Dittmar & J.J.Colledge. It reads: “THALIA, harbour service, store hulk, Cromarty; base ship 2.15 (ex-wooden screw corvette, Juno-class), built 1869, 2240 tons. Sold 16.9.20.”. The current edition of ‘Ships of the Royal Navy, by J.J.Colledge & Ben Warlow, (Casemate, 2010), also records Thalia as being commissioned as a ‘base ship’ in February 1915, and then sold to Rose Street Foundry in Inverness in September 1920, although it makes no reference to where she served as a base ship. Neither entry states why Rose Street Foundry bought her, although it has been assumed that it was for breaking.

Elsewhere, it is claimed that this Thalia was the ‘mothership’ for Area IV of the Auxiliary Patrol anti-submarine and mine-sweeping service for the Cromarty Firth, which was established between December 1914 and August 1915.

I believe that J.J.Colledge is generally regarded as a reliable authority on such matters and that the books he authored are standard reference works for naval historians. It seems likely therefore that there was a base ship at Cromarty called Thalia, and her proposed fate in Inverness, twenty miles or so distant from Cromarty is therefore at least plausible. I have however three concerns with the Cromarty scenario as an account of the fate of the ‘Woolwich Thalia’:

First, assuming that they are the same ship, it seems extraordinary that it was considered worth the expense and considerable risk to tow such a venerable hulk (she would have been over 40 years old at the time) about 600 miles from Woolwich to Cromarty, through the North Sea, with WW1 having already begun (there was no need for such a ‘mothership’ until the Auxiliary Patrols were formed in 1915, so it would seem unlikely that she would have been moved to Cromarty before then). Were suitable candidates for base-ships really so hard to come by in the Cromarty Firth?

Second, I can find no reference to Rose Street Foundry being engaged in ship-breaking activities in Inverness. It seems at least part of their business was as marine engineers and there are accounts of their involvement in repairing coasters and fishing vessels, but I have found no mention of them being involved in ship-breaking or scrap activities.

Third, if the ship in question was the Thalia previously at Woolwich, one has to ask what Rose Street Foundry - who were engineers in metal - would want with the hull of a large wooden ship. It is possible that, like Cutty Sark (built at around the same time), Thalia was of composite construction with iron frames, and with external copper or Muntz metal sheathing beneath the waterline. If so, it might have been financially worthwhile to buy her and to tow her the twenty miles to Inverness for breaking. Unfortunately, I have not been able to discover any details of the precise method used in the construction of HMS Thalia so I cannot say with any confidence that she was of composite construction. Nor do I know the relative value at the time of wrought iron frames, or of Muntz metal, or the costs of towage and breaking, or indeed what was paid for the hulk - so I cannot make any informed judgement of the economic case, although it might seem an improbable way for Rose Street Foundry to make a profit.

On the other hand, neither have I been able to find any evidence on which to base an alternative account of her fate, so it remains theoretically possible that she was towed to Cromarty for use as a Base Ship and that she was eventually scrapped in Inverness.