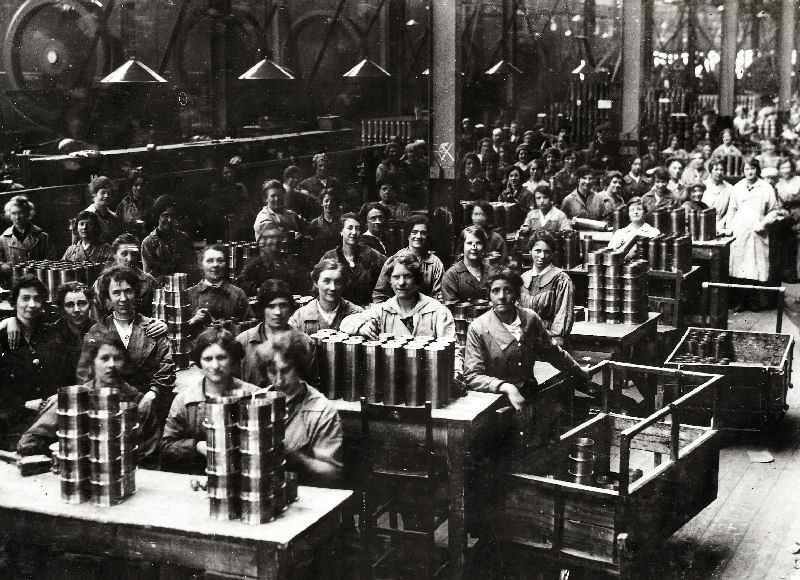

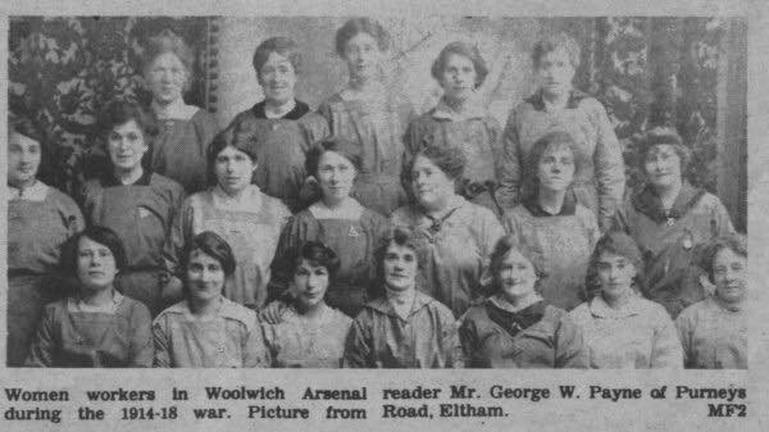

Women Workers WW1

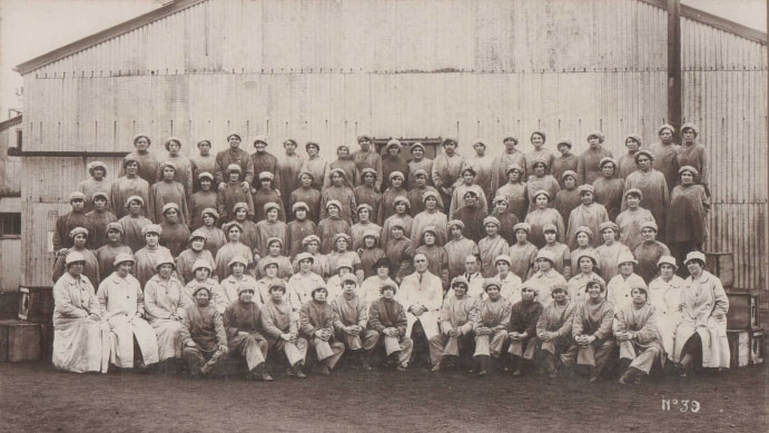

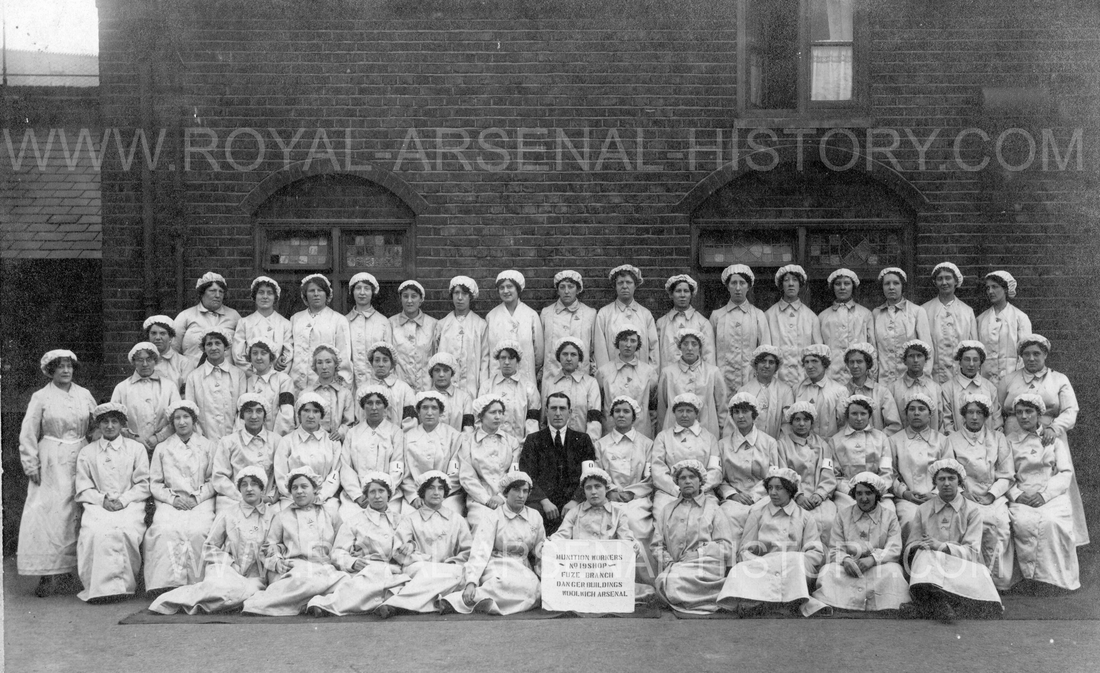

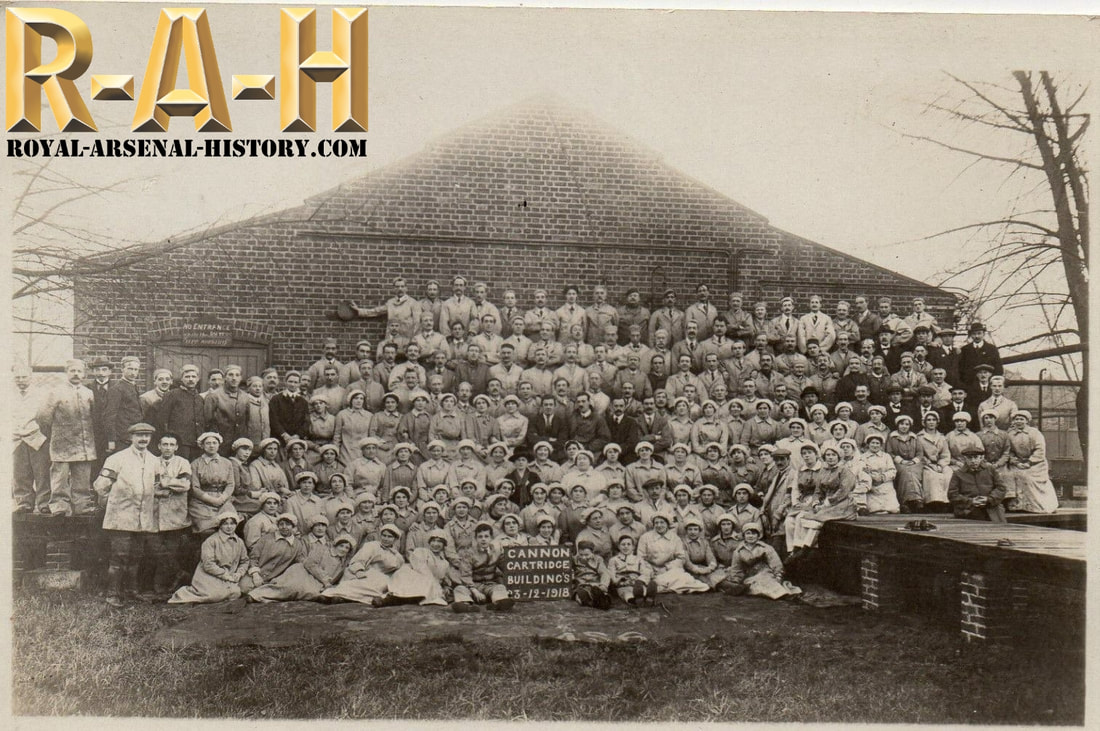

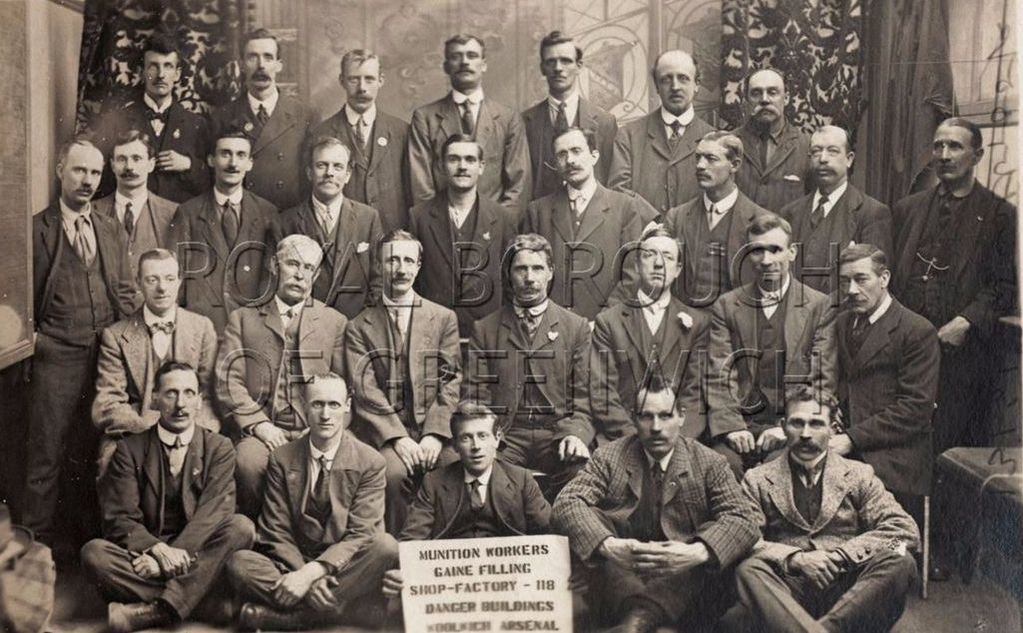

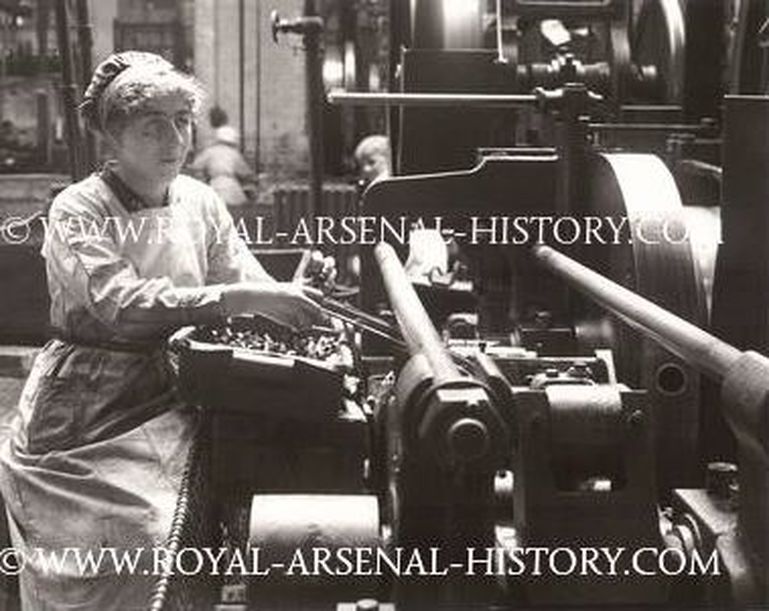

For the first eighteen months of the Great War, nearly all of the army's gun ammunition was filled at Woolwich, yet at the start of 1914 the Arsenal employed only half as many men as it had in 1901. At the start of the battle of Neuve Chapelle on 10th March 1915, the army would fire more shells in the opening barrage than had been fired in the whole of the Boer War. The Arsenal could not meet this scale of demand on its own, even with the men working 96 hours a week with just one day off every four weeks. The army's acute shortage of shells in the Spring of 1915 led to a political scandal - the Shell Scandal. The Prime Minister, Asquith, was forced into coalition government, and control of the Royal Ordnance Factories was transferred from Kitchener's War Office to a new Ministry of Munitions under Lloyd-George. He soon realised that only the mass employment of unskilled men and women in the factories could meet the army's needs. This "Dilution" of skill was negotiated with the trade unions, and from October 1915 the first women to work in the Arsenal since the previous century started their shifts. By the end of 1917 nearly 26,000 women - 35% of the Ordnance Factory workforce - worked in the Arsenal, mostly in shell filling and fuze and gaine assembly.

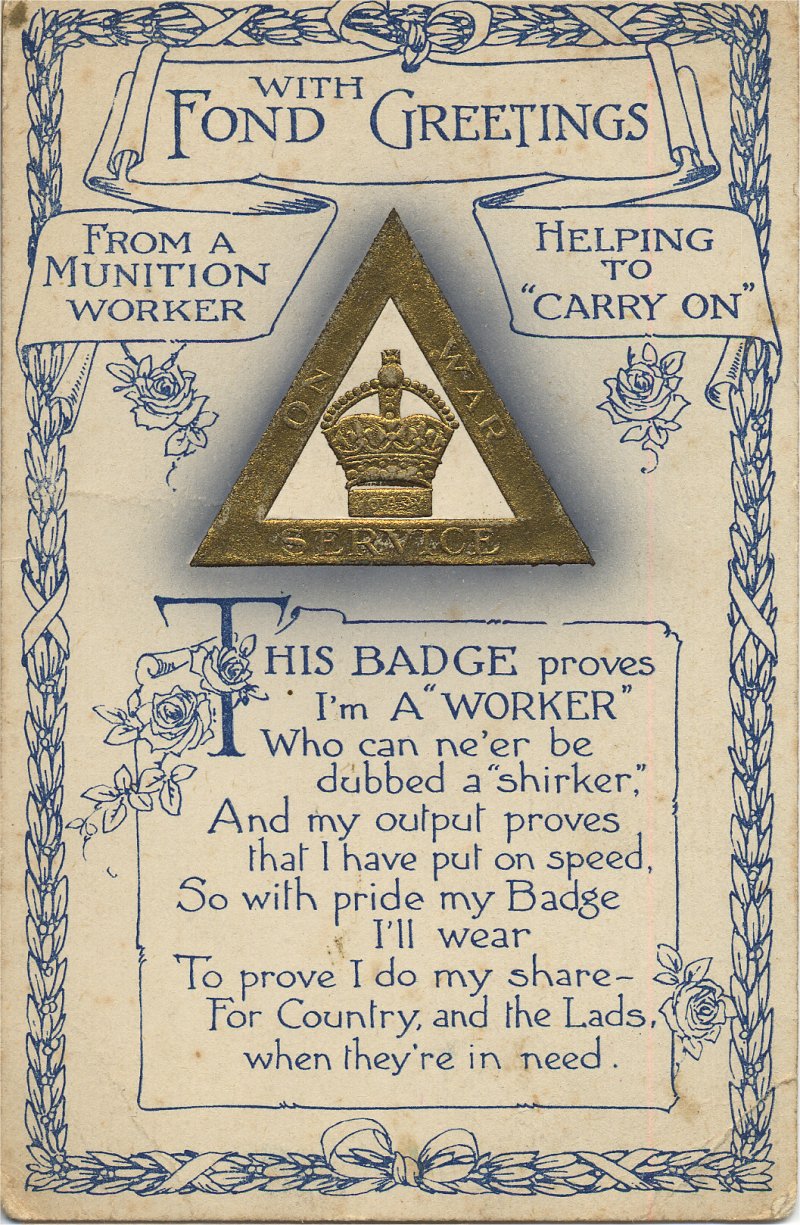

Munitions workers played a crucial role in the First World War. They supplied the troops at the front with the armaments and equipment they needed to fight. They also freed up men from the workforce to join the armed forces.

Following a shortage of shells in 1915, the Ministry of Munitions was founded to control Britain's output of war material. It oversaw all aspects of the production and supply of munitions, under the forceful and energetic Minister for Munitions.

A number of new initiatives were soon introduced to improve production levels. One of these was an appeal to women to register for war service work. Thousands of women volunteered as a result, and many of these were soon employed in the growing number of munitions factories across the country. By the end of the war, over 700,000 – and possibly up to one million – women had become ‘munitionettes’.

The munitionettes worked long hours in often hazardous conditions.

Following a shortage of shells in 1915, the Ministry of Munitions was founded to control Britain's output of war material. It oversaw all aspects of the production and supply of munitions, under the forceful and energetic Minister for Munitions.

A number of new initiatives were soon introduced to improve production levels. One of these was an appeal to women to register for war service work. Thousands of women volunteered as a result, and many of these were soon employed in the growing number of munitions factories across the country. By the end of the war, over 700,000 – and possibly up to one million – women had become ‘munitionettes’.

The munitionettes worked long hours in often hazardous conditions.

WW1 Women worker videos

Ethel May Dean with overlay of related photos - Woolwich Arsenal

Women workers in the Woolwich Arsenal with audio overlay Caroline Rennles and discussions about Cartridge Factory 5.

This rare high quality Royal Arsenal Woolwich video showcases the process of shell case-making, which was an important part of munitions production during the First World War. The video is overlaid with oral history given by Caroline Rennles, who provides an account of her time working as a munitions worker at the Woolwich Arsenal in London, GB, between 1917 and 1918.

In her interview, she talks about her move to the Woolwich Arsenal factory, where she worked long hours under challenging conditions. She also discusses the measures taken to protect the workers during air raids, which were a frequent occurrence in London during the war. she provides insight into the head overlooker Lilian Barker, who was well-respected among her peers. Lilian Barker's expertise and dedication were crucial to the success of the munitions production effort, and she became a well-respected figure in the industry.

After the war, Barker continued to work in the field of engineering and was later appointed a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire for her contributions to the profession. Her legacy as a pioneering woman in engineering and leadership.

Additionally, Caroline discusses the difficulties faced by the workers, such as pay cuts and accidents, and how they ultimately formed a union to advocate for their rights. The audio interview was recorded in 1975 and provides a valuable perspective on the experiences of women workers during the First World War. Nights out at Beresford Square from Plumstead gate.

The Royal Arsenal Woolwich video and accompanying oral history provide a fascinating glimpse into the production of munitions during the First World War and the experiences of the workers who played a crucial role in the war effort.

This rare high quality Royal Arsenal Woolwich video showcases the process of shell case-making, which was an important part of munitions production during the First World War. The video is overlaid with oral history given by Caroline Rennles, who provides an account of her time working as a munitions worker at the Woolwich Arsenal in London, GB, between 1917 and 1918.

In her interview, she talks about her move to the Woolwich Arsenal factory, where she worked long hours under challenging conditions. She also discusses the measures taken to protect the workers during air raids, which were a frequent occurrence in London during the war. she provides insight into the head overlooker Lilian Barker, who was well-respected among her peers. Lilian Barker's expertise and dedication were crucial to the success of the munitions production effort, and she became a well-respected figure in the industry.

After the war, Barker continued to work in the field of engineering and was later appointed a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire for her contributions to the profession. Her legacy as a pioneering woman in engineering and leadership.

Additionally, Caroline discusses the difficulties faced by the workers, such as pay cuts and accidents, and how they ultimately formed a union to advocate for their rights. The audio interview was recorded in 1975 and provides a valuable perspective on the experiences of women workers during the First World War. Nights out at Beresford Square from Plumstead gate.

The Royal Arsenal Woolwich video and accompanying oral history provide a fascinating glimpse into the production of munitions during the First World War and the experiences of the workers who played a crucial role in the war effort.

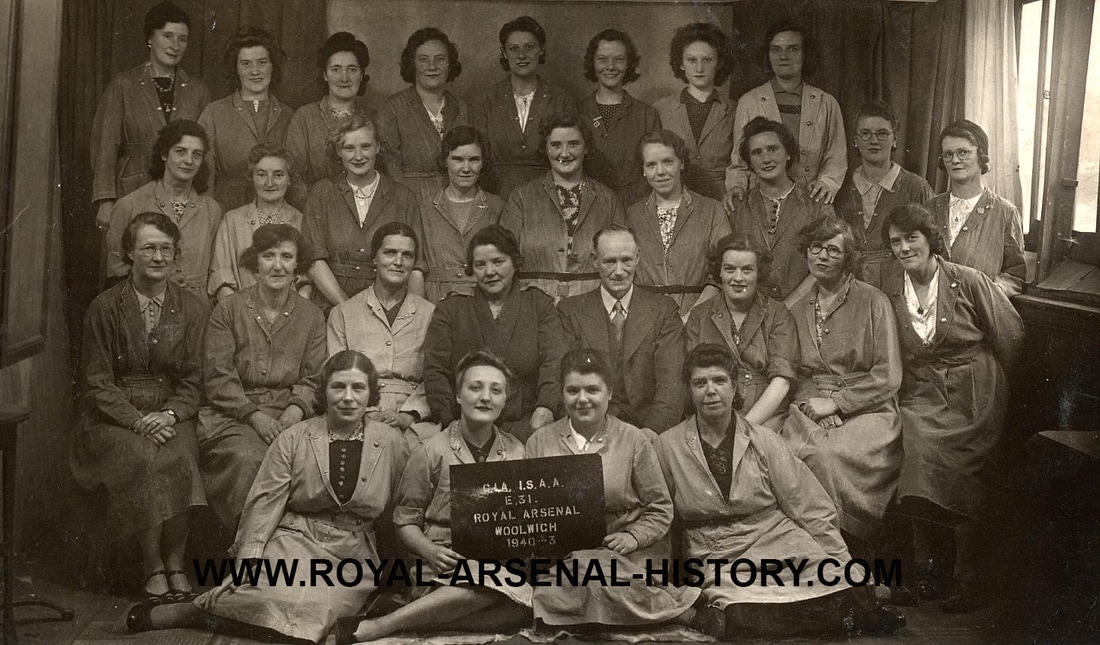

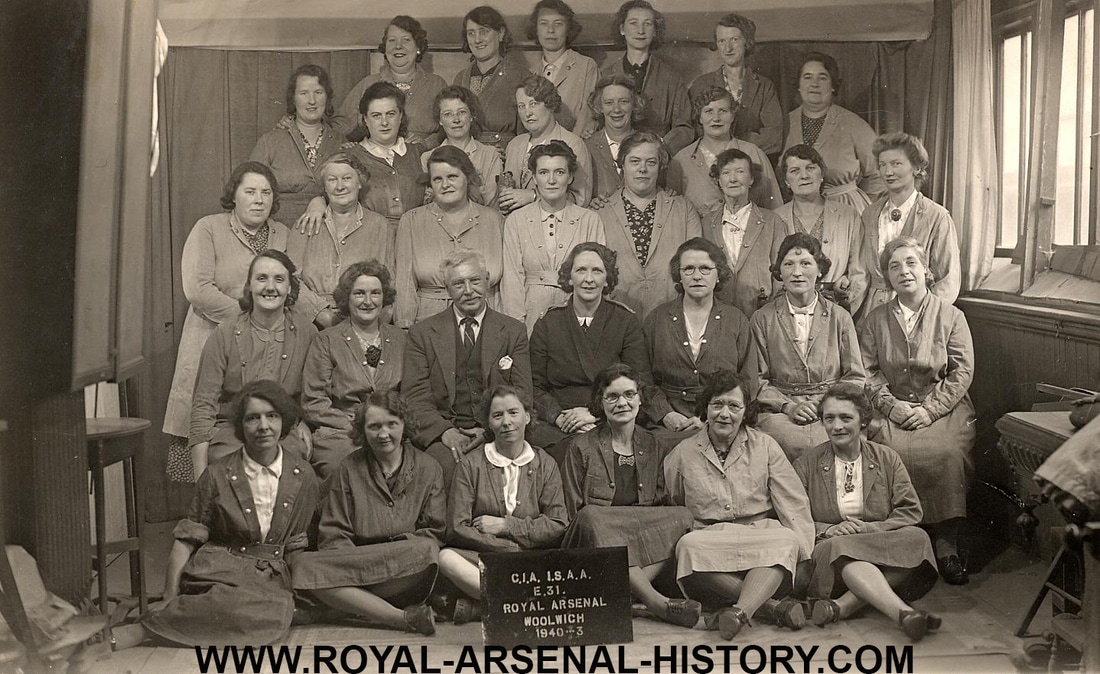

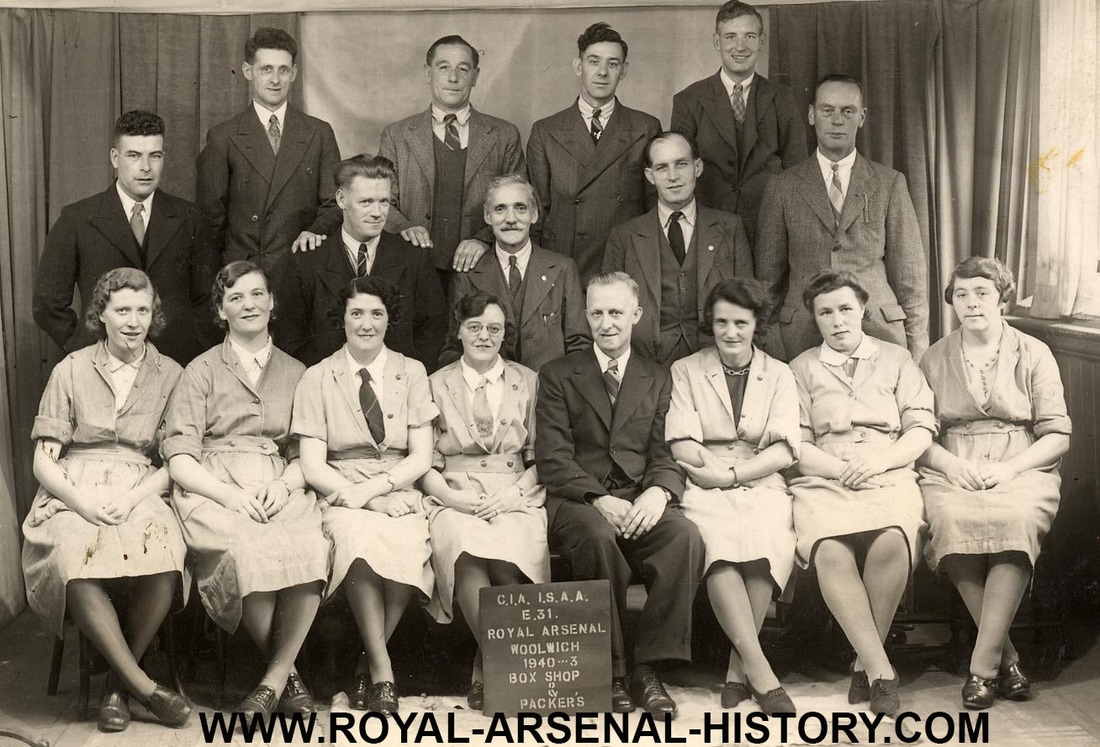

Women Workers WW2 video

Working Life

PART 1 - A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A MUNITION WORKER CHILWELL, NOTTINGHAM

Manual work done by women at a British munitions factory (Chilwell, Nottingham) 1917.

The staggering demand for artillery shells posed a problem for a British army that was hopelessly ill-equipped at the war’s commencement. Woolwich arsenal could not match the demand, leading to such a shortfall of shells that, over a year into the war in 1915, artillery units were still having to heavily ration the number of shells they could fire in a day.

During World War One, there was a high demand for munitions, which led to an increase in the number of women working in factories. The Chilwell shell filling factory in Nottingham was no exception, where women played a vital role in the production of shells.

The day of a young woman working at the Chilwell factory started early. She would leave her home at 5 am and take the train to the factory. After changing into overalls and boots in the locker room, she would clock on and begin her work on finishing 8-inch shells. This involved pouring molten explosive into the shell cases, capping them using a wheel to clear the screw threads, adding the detonator, and stenciling them. A trolley would then take the shells away.

Other women, wearing masks against the fumes, were responsible for topping up heavier shells. The women were given a brief medical examination on-site, with blood samples taken in some suspect cases. The women wore shifts to wash, which was compulsory before meals and on leaving the factory.

PART 2 - DAILY LIFE IN NATIONAL SHELL FILLING FACTORY No.6 AT CHILWELL DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR

The rare footage of the National Shell Filling Factory No6 at Chilwell in Nottingham provides a glimpse into the daily life of workers during World War One.

The video highlights the work of both male and female workers in the factory, but it is clear that women played a significant role in the process.

Female workers are seen unloading shell cases from wagons, marking them using stencils and paint, preparing plugs for sealing filled shells, and operating cranes to move shells around the factory. The video also shows women wearing masks while filling heavier shells with explosive material.

It is worth noting that the first women employed at the factory were employed as crane operators, a role traditionally reserved for men. This shows the extent to which women were willing and able to take on manual labour during the war effort.

The Kodak film, which was found in a shed in a town, was restored by staff at the Imperial War Museum in London over a period of four years.

Finding workers to address the problem of shell production was another challenge since the heart of Britain’s engineering workforce had been sent to the Western Front, and retraining older workers proved difficult. The solution was to hire women who had not previously been tapped as a workforce.

Female workers were efficient in performing delicate tasks involved in shell production and soon proved themselves more than able to produce shells. By 1916, the Chilwell factory, established by Viscount Chetwynd, had produced over a million shells, 25,000 mines, and 2,500 large bombs for the RAF, with around 40% of the workforce being women. The factory employed 4,000 women who worked 12-hour shifts, and by June 1918, it set a national record by producing 46,725 shells in a single 24-hour period. Despite the hazards and constant safety concerns involved in the work, human safety was overlooked in favour of efficient productivity.

In July 1918, just four months before the war's end, a devastating explosion tore through the factory, killing 134 people and injuring another 250, and causing the biggest explosive disaster in Britain’s history. The cause of the explosion remains a mystery to date. A small obelisk stands at the site to commemorate the victims of the disaster. The factory played an integral role in Britain's war effort, and the unexploded shells from that time are still being discovered today in Flanders Fields, with at least one fatality a year, and a dedicated Belgian army squad deals with the collection and destruction of the dormant shells.

Manual work done by women at a British munitions factory (Chilwell, Nottingham) 1917.

The staggering demand for artillery shells posed a problem for a British army that was hopelessly ill-equipped at the war’s commencement. Woolwich arsenal could not match the demand, leading to such a shortfall of shells that, over a year into the war in 1915, artillery units were still having to heavily ration the number of shells they could fire in a day.

During World War One, there was a high demand for munitions, which led to an increase in the number of women working in factories. The Chilwell shell filling factory in Nottingham was no exception, where women played a vital role in the production of shells.

The day of a young woman working at the Chilwell factory started early. She would leave her home at 5 am and take the train to the factory. After changing into overalls and boots in the locker room, she would clock on and begin her work on finishing 8-inch shells. This involved pouring molten explosive into the shell cases, capping them using a wheel to clear the screw threads, adding the detonator, and stenciling them. A trolley would then take the shells away.

Other women, wearing masks against the fumes, were responsible for topping up heavier shells. The women were given a brief medical examination on-site, with blood samples taken in some suspect cases. The women wore shifts to wash, which was compulsory before meals and on leaving the factory.

PART 2 - DAILY LIFE IN NATIONAL SHELL FILLING FACTORY No.6 AT CHILWELL DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR

The rare footage of the National Shell Filling Factory No6 at Chilwell in Nottingham provides a glimpse into the daily life of workers during World War One.

The video highlights the work of both male and female workers in the factory, but it is clear that women played a significant role in the process.

Female workers are seen unloading shell cases from wagons, marking them using stencils and paint, preparing plugs for sealing filled shells, and operating cranes to move shells around the factory. The video also shows women wearing masks while filling heavier shells with explosive material.

It is worth noting that the first women employed at the factory were employed as crane operators, a role traditionally reserved for men. This shows the extent to which women were willing and able to take on manual labour during the war effort.

The Kodak film, which was found in a shed in a town, was restored by staff at the Imperial War Museum in London over a period of four years.

Finding workers to address the problem of shell production was another challenge since the heart of Britain’s engineering workforce had been sent to the Western Front, and retraining older workers proved difficult. The solution was to hire women who had not previously been tapped as a workforce.

Female workers were efficient in performing delicate tasks involved in shell production and soon proved themselves more than able to produce shells. By 1916, the Chilwell factory, established by Viscount Chetwynd, had produced over a million shells, 25,000 mines, and 2,500 large bombs for the RAF, with around 40% of the workforce being women. The factory employed 4,000 women who worked 12-hour shifts, and by June 1918, it set a national record by producing 46,725 shells in a single 24-hour period. Despite the hazards and constant safety concerns involved in the work, human safety was overlooked in favour of efficient productivity.

In July 1918, just four months before the war's end, a devastating explosion tore through the factory, killing 134 people and injuring another 250, and causing the biggest explosive disaster in Britain’s history. The cause of the explosion remains a mystery to date. A small obelisk stands at the site to commemorate the victims of the disaster. The factory played an integral role in Britain's war effort, and the unexploded shells from that time are still being discovered today in Flanders Fields, with at least one fatality a year, and a dedicated Belgian army squad deals with the collection and destruction of the dormant shells.

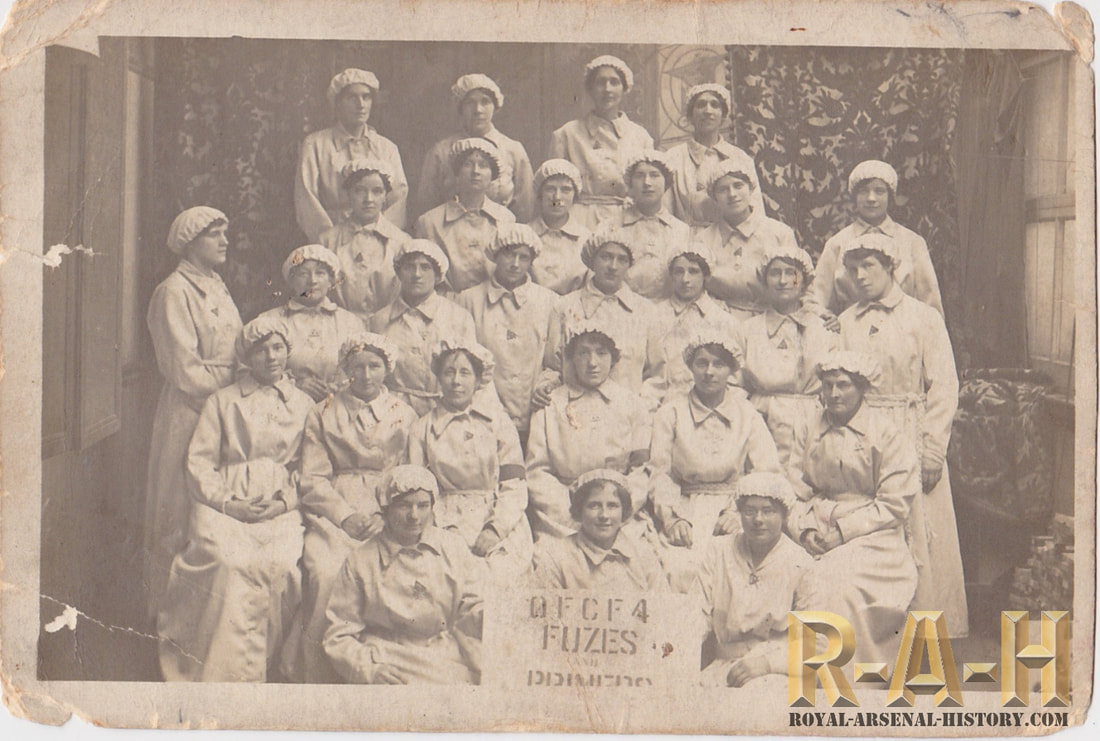

1918 Fuze girls

This high quality video takes us back to 1918, during World War I, at the Woolwich Royal Arsenal in London (ROF - Royal Ordnance Factory Number 1). The Woolwich Arsenal was a major factory for the manufacture of munitions during the war, and the video shows us a glimpse of the dedicated women who worked there.

As the song "Keep The Home Fires Burning" by Laura Wright plays, we see a somber-looking woman worker, perhaps thinking about her loved ones fighting in the war. Then, the video takes us to a view inside the factory where we see women working to manufacture fuses.

The rare video shows the different stages of fuse production, from punching discs for primers to ganging primers for 18-pounders, boring and screwing high explosive fuse bodies, and cleaning operations with emery band. The women are shown working with precision and dedication as they assemble a time fuse. The work is labour-intensive and requires a high level of skill and attention to detail.

During World War I, many women took on jobs traditionally held by men, as the men were off fighting in the war. At the Woolwich Arsenal, women played a vital role in producing the munitions that were crucial to the war effort. The video highlights the importance of the work done by these women in producing the fuses that were vital to the war effort, and provides a glimpse into the lives of women during wartime.

Halfway through the video, the music changes to "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" and "Pack up Your Troubles (March Medley)" to give the video some life. These songs were popular during the war and would have been familiar to the workers at the Woolwich Arsenal.

This video is a tribute to the sacrifices made by the women and the men who fought in the war, and to the important role that women played in the war effort. It shows us a fascinating glimpse into the past and reminds us of the bravery and dedication of those who fought and worked to protect their country.

As the song "Keep The Home Fires Burning" by Laura Wright plays, we see a somber-looking woman worker, perhaps thinking about her loved ones fighting in the war. Then, the video takes us to a view inside the factory where we see women working to manufacture fuses.

The rare video shows the different stages of fuse production, from punching discs for primers to ganging primers for 18-pounders, boring and screwing high explosive fuse bodies, and cleaning operations with emery band. The women are shown working with precision and dedication as they assemble a time fuse. The work is labour-intensive and requires a high level of skill and attention to detail.

During World War I, many women took on jobs traditionally held by men, as the men were off fighting in the war. At the Woolwich Arsenal, women played a vital role in producing the munitions that were crucial to the war effort. The video highlights the importance of the work done by these women in producing the fuses that were vital to the war effort, and provides a glimpse into the lives of women during wartime.

Halfway through the video, the music changes to "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" and "Pack up Your Troubles (March Medley)" to give the video some life. These songs were popular during the war and would have been familiar to the workers at the Woolwich Arsenal.

This video is a tribute to the sacrifices made by the women and the men who fought in the war, and to the important role that women played in the war effort. It shows us a fascinating glimpse into the past and reminds us of the bravery and dedication of those who fought and worked to protect their country.

Working conditions

Becoming a ‘Canary’

Munitions workers whose job was filling shells were prone to suffer from TNT poisoning. TNT stood for Trinitrotoluene – an explosive which turned the skin yellow of those who regularly came into contact with it. The munitions workers who were affected by this were commonly known as ‘canaries’ due to their bright yellow appearance. Although the visible effects usually wore off, some women died from working with TNT, if they were exposed to it for a prolonged period. As Ethel Dean, who worked at Woolwich Arsenal, recalled, ‘Everything that that powder touches goes yellow. All the girls’ faces were yellow, all round their mouths. They had their own canteen, in which everything was yellow that they touched… Everything they touched went yellow – chairs, tables, everything

Munitions workers whose job was filling shells were prone to suffer from TNT poisoning. TNT stood for Trinitrotoluene – an explosive which turned the skin yellow of those who regularly came into contact with it. The munitions workers who were affected by this were commonly known as ‘canaries’ due to their bright yellow appearance. Although the visible effects usually wore off, some women died from working with TNT, if they were exposed to it for a prolonged period. As Ethel Dean, who worked at Woolwich Arsenal, recalled, ‘Everything that that powder touches goes yellow. All the girls’ faces were yellow, all round their mouths. They had their own canteen, in which everything was yellow that they touched… Everything they touched went yellow – chairs, tables, everything

Health hazards

As well as handling the hazardous TNT powder, munitions workers risked their health in other ways in the busy, dangerous factories. The working conditions varied, but they often featured poor ventilation, exposure to harmful chemicals and sometimes even asbestos; and the physical labour involved – which included lifting heavy shells and operating machinery – could be back-breaking or extremely risky.

As well as handling the hazardous TNT powder, munitions workers risked their health in other ways in the busy, dangerous factories. The working conditions varied, but they often featured poor ventilation, exposure to harmful chemicals and sometimes even asbestos; and the physical labour involved – which included lifting heavy shells and operating machinery – could be back-breaking or extremely risky.

Noisy conditions

Depending on the type of production that was being carried out, the munitions factories could be very noisy working environments. With heavy machines operating, workers shouting at each other and moving heavy shells and equipment around, the factories were often deafening places to be.

Workplace accidents

Working as they did long before modern-day health and safety legislation, workplace accidents were not unusual for employees of the munitions factories. From relatively minor injuries to more serious incidents and even death, munitions workers risked their health and often their lives while carrying out their jobs. The exact number of fatalities is difficult to know: many of these cases were kept out of the press, due to the impact such news would have had on national morale and the war effort. Henry Oxley remembered from his time at Woolwich Arsenal, ‘Prevalent in my particular job was filings coming off the machine into one’s eyes. There was no protection to shield your eyes from the filings coming up. And that was an occurrence which happened quite often.’ (IWM SR 716)

Threat of explosion

There were a number of explosions at munitions factories during the First World War. The massive amount of explosive material kept at the factories meant this was an ever-present danger for those working at them. One of the largest of these disasters occurred at Silvertown, in London’s East End, in January 1917. As many as 73 people were killed, and 400 were injured. Florence Parsons, who was working nearby, remembered the huge sound the factory made as it went up: ‘A terrible explosion went. We thought it was a Zeppelin over the top of us – it really rocked us… Oh the explosion, it rocked everywhere.’ (IWM SR 11462) As key centres of war production, munitions factories were also particular targets for enemy air raids, adding another element of danger to working at them.

Long hours

The working day for a munitions worker varied according to where he or she was employed but, due to the pressures and demands of war production, they generally had to work long hours. Usually a shift system operated, and some workers also put in overtime. The length of time the shifts lasted were not standardised but could be up to 12 hours' long, as many factories operated both day and night. Many munitions workers later remembered how exhausting the night shifts were and the difficulty of staying alert when working them.

Short breaks

Despite such a tiring working day, munitions workers didn’t have many – or particularly long – breaks. Some even remembered having no breaks at all. The better factories provided canteens, washrooms and toilet facilities for their employees, but these were not to be found at every workplace. When Kathleen Gilbert was a munitions worker in London, her hours were, ‘from 6am to 5.30pm, standing all the time. We had a 10 minute break, to go to the toilets, and we had to stand and eat sandwiches at the machine.’ (IWM SR 9105)

Repetitive work

Munitions workers carried out a wide range of jobs during the war, and were involved in the manufacturing of a variety of armaments and equipment essential to the war effort. They could be engaged in: cleaning, filling, painting and stacking shells; operating machinery; weighing powder; assembling detonators; filling bullets; lacquering fuses and making shell cases. It was often repetitive – but they had to stay focused, as their work was checked and needed to meet the required standards.

Strict rules

Due to the risk of explosion at the factories, strict regulations were put in place to reduce the chances of accidents happening. The workers wore wooden clogs so as to avoid the sparks that could be caused by shoes with any metal in them. Other metal items were prohibited, including jewellery and hairpins.

Depending on the type of production that was being carried out, the munitions factories could be very noisy working environments. With heavy machines operating, workers shouting at each other and moving heavy shells and equipment around, the factories were often deafening places to be.

Workplace accidents

Working as they did long before modern-day health and safety legislation, workplace accidents were not unusual for employees of the munitions factories. From relatively minor injuries to more serious incidents and even death, munitions workers risked their health and often their lives while carrying out their jobs. The exact number of fatalities is difficult to know: many of these cases were kept out of the press, due to the impact such news would have had on national morale and the war effort. Henry Oxley remembered from his time at Woolwich Arsenal, ‘Prevalent in my particular job was filings coming off the machine into one’s eyes. There was no protection to shield your eyes from the filings coming up. And that was an occurrence which happened quite often.’ (IWM SR 716)

Threat of explosion

There were a number of explosions at munitions factories during the First World War. The massive amount of explosive material kept at the factories meant this was an ever-present danger for those working at them. One of the largest of these disasters occurred at Silvertown, in London’s East End, in January 1917. As many as 73 people were killed, and 400 were injured. Florence Parsons, who was working nearby, remembered the huge sound the factory made as it went up: ‘A terrible explosion went. We thought it was a Zeppelin over the top of us – it really rocked us… Oh the explosion, it rocked everywhere.’ (IWM SR 11462) As key centres of war production, munitions factories were also particular targets for enemy air raids, adding another element of danger to working at them.

Long hours

The working day for a munitions worker varied according to where he or she was employed but, due to the pressures and demands of war production, they generally had to work long hours. Usually a shift system operated, and some workers also put in overtime. The length of time the shifts lasted were not standardised but could be up to 12 hours' long, as many factories operated both day and night. Many munitions workers later remembered how exhausting the night shifts were and the difficulty of staying alert when working them.

Short breaks

Despite such a tiring working day, munitions workers didn’t have many – or particularly long – breaks. Some even remembered having no breaks at all. The better factories provided canteens, washrooms and toilet facilities for their employees, but these were not to be found at every workplace. When Kathleen Gilbert was a munitions worker in London, her hours were, ‘from 6am to 5.30pm, standing all the time. We had a 10 minute break, to go to the toilets, and we had to stand and eat sandwiches at the machine.’ (IWM SR 9105)

Repetitive work

Munitions workers carried out a wide range of jobs during the war, and were involved in the manufacturing of a variety of armaments and equipment essential to the war effort. They could be engaged in: cleaning, filling, painting and stacking shells; operating machinery; weighing powder; assembling detonators; filling bullets; lacquering fuses and making shell cases. It was often repetitive – but they had to stay focused, as their work was checked and needed to meet the required standards.

Strict rules

Due to the risk of explosion at the factories, strict regulations were put in place to reduce the chances of accidents happening. The workers wore wooden clogs so as to avoid the sparks that could be caused by shoes with any metal in them. Other metal items were prohibited, including jewellery and hairpins.

For the women to work in these `Danger Buildings` a routine twice a day exercise had to be undertaken before entering or leaving the area. They had to pass through the `Shifting House` which was a long building divided by a red barrier, one side being the dirty side, and the other side the clean. On arriving to start their shift their outdoor clothing, jewellary, hairpins were removed along with any matches and metallic items in their pockets. They would be checked for any metallic fasters on their under garments, only lace up corsets could be warn, before they could pass to the clean side and put on their regulation cream coloured gowns buttoned right up to their neck and tight around their wrists. On their heads they had to wear tightly fitted caps with as much hair tucked away under it. Of course to end a shift or to leave the danger buildings area for any reason the complete reversal had to be undertaken.

Nursery for Children

1915 Women Munition Workers enrol at once - On Her Their Lives Depend

"They don't breed Women like that anymore"

Of course the `Danger Buildings` were not the only place the women worked. There were the likes of the `Tailor's Shop` were the items such as the cartridge bags were made and also all the clothing for the `Danger Building` workers. The Tailors Shop many jobs were undertaken by the women, and this was quoted once by a male who worked along side a group of women in the Royal Arsenal :-

" The thing that I remember was their amazing cheerfulness." They seldom complained and the twelve hour day never seemed to never tire them." In many ways, they were better than the men at some of the work they were called on to do." Their fingers were quick and nimble and you didn't often find and shirking." "And a lot of them did men's jobs like driving trucks and lifting heavy shell cases all day." and to add all that off he also said, " they don't breed women like that lot any more ! ".

Of course the `Danger Buildings` were not the only place the women worked. There were the likes of the `Tailor's Shop` were the items such as the cartridge bags were made and also all the clothing for the `Danger Building` workers. The Tailors Shop many jobs were undertaken by the women, and this was quoted once by a male who worked along side a group of women in the Royal Arsenal :-

" The thing that I remember was their amazing cheerfulness." They seldom complained and the twelve hour day never seemed to never tire them." In many ways, they were better than the men at some of the work they were called on to do." Their fingers were quick and nimble and you didn't often find and shirking." "And a lot of them did men's jobs like driving trucks and lifting heavy shell cases all day." and to add all that off he also said, " they don't breed women like that lot any more ! ".

John Harvey - 24 Oct 2004

Dear Readers, I thought I would see what turned up under Woolwich Arsenal Factory WW1 and was amazed that so many people are seeking names and contacts. I can only respond with some memories that my dear old mum used to tell us about. Her name was Nina Owen then, died aged 96, born 1898 She lived in Stoke Newington, London during first-world war. She used to walk from there to South Tottenham Station every morning, about 5 miles, to catch a train to Woolwich where she worked filling shells with gunpowder. She remembers a terrible explosion at one time that killed many workers. She would fascinate me about a song the girls used to sing, and to best of my memory it went like this....

We are the ammunition girls, working day by day,

Wearing the roses off our cheeks, for very little pay.

Why do they call us Canary Girls, we are as happy as the birds upon the sea.

If it wasn't for the Ammunition Girls, where would the Empire be....

The reference to Canary Girls was because their faces would become stained with yellow from handling the gunpowder..

Dear Readers, I thought I would see what turned up under Woolwich Arsenal Factory WW1 and was amazed that so many people are seeking names and contacts. I can only respond with some memories that my dear old mum used to tell us about. Her name was Nina Owen then, died aged 96, born 1898 She lived in Stoke Newington, London during first-world war. She used to walk from there to South Tottenham Station every morning, about 5 miles, to catch a train to Woolwich where she worked filling shells with gunpowder. She remembers a terrible explosion at one time that killed many workers. She would fascinate me about a song the girls used to sing, and to best of my memory it went like this....

We are the ammunition girls, working day by day,

Wearing the roses off our cheeks, for very little pay.

Why do they call us Canary Girls, we are as happy as the birds upon the sea.

If it wasn't for the Ammunition Girls, where would the Empire be....

The reference to Canary Girls was because their faces would become stained with yellow from handling the gunpowder..

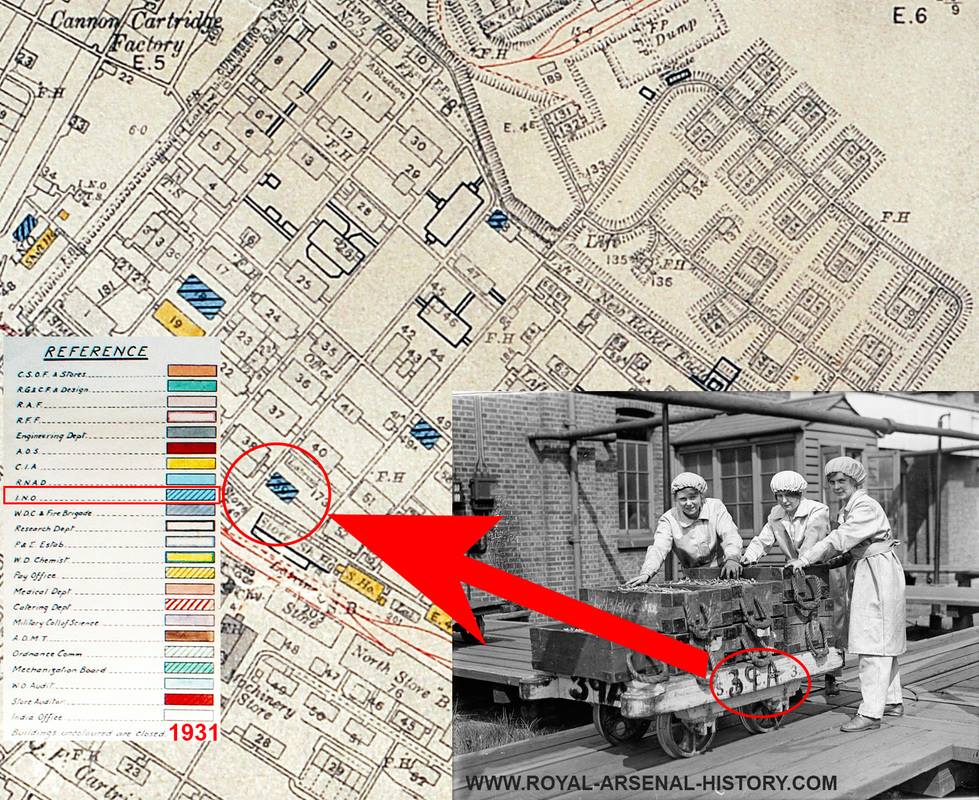

Women Workers in the Danger Buildings

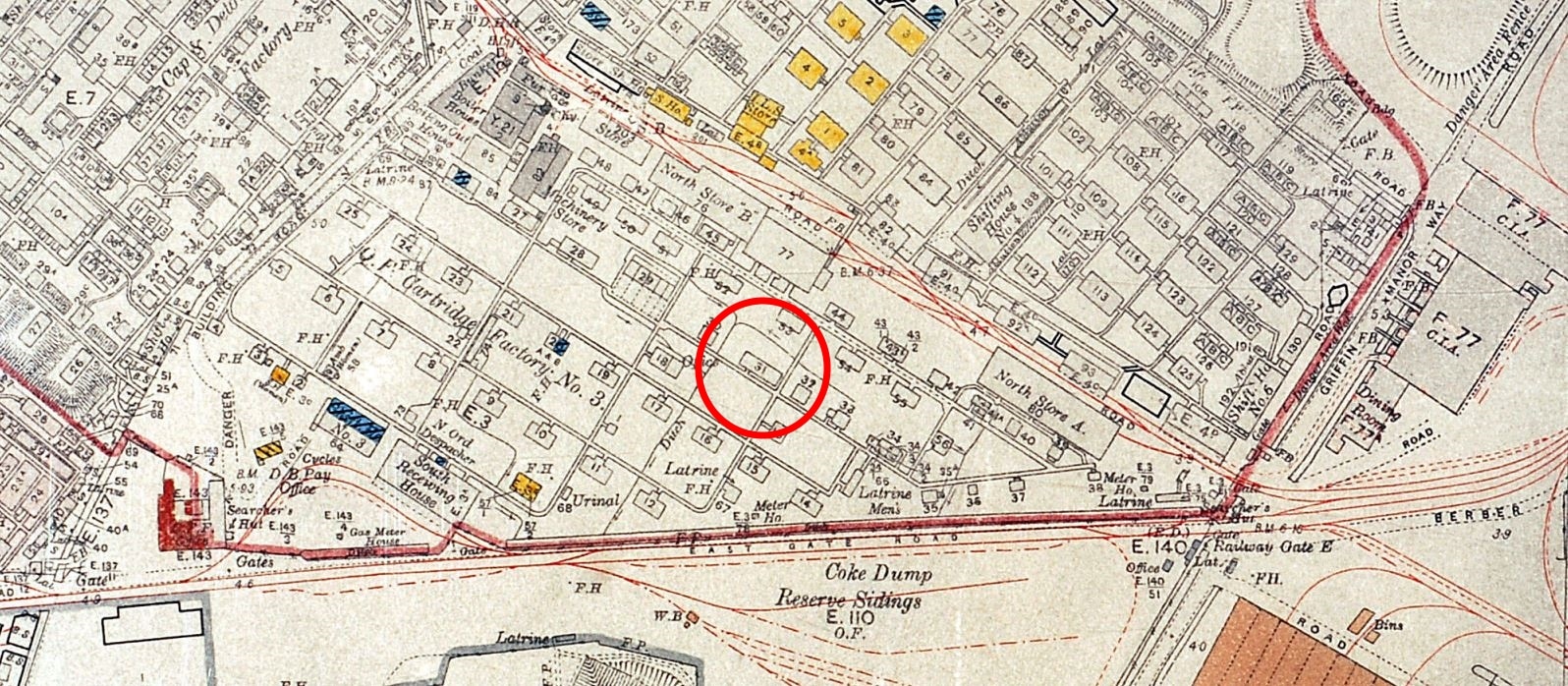

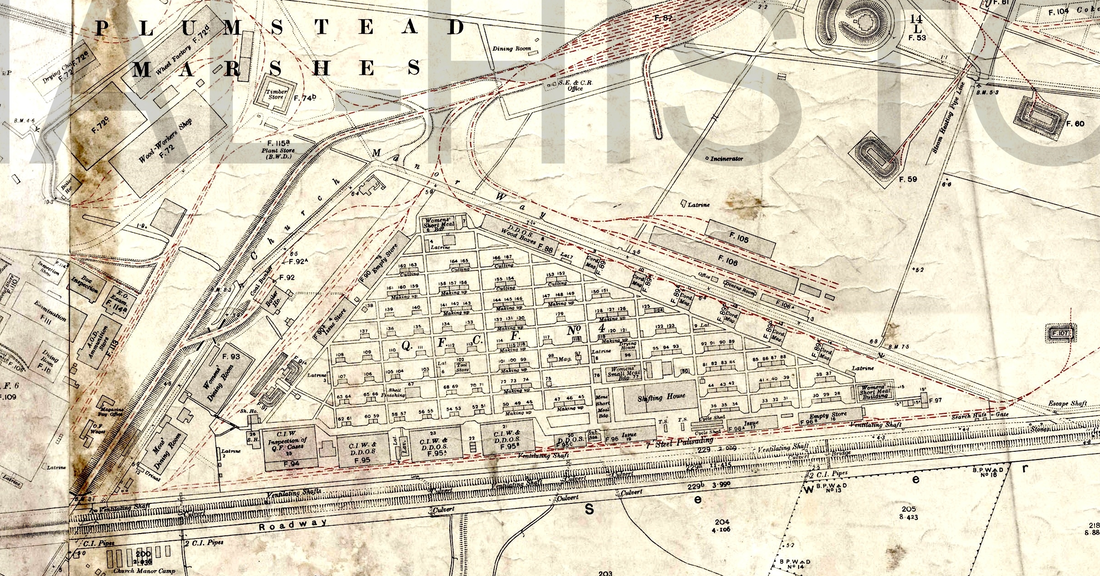

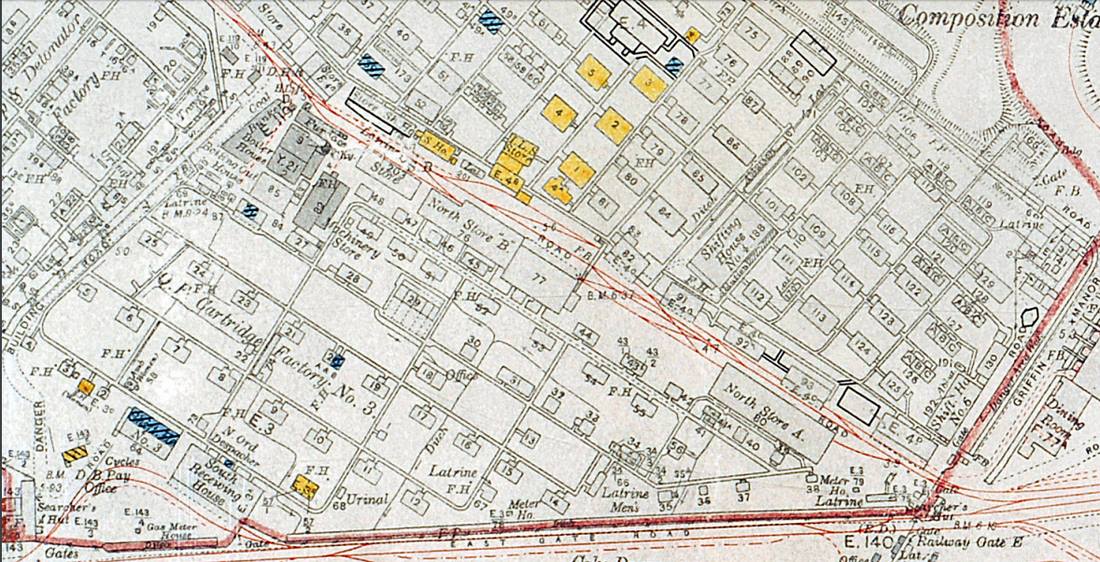

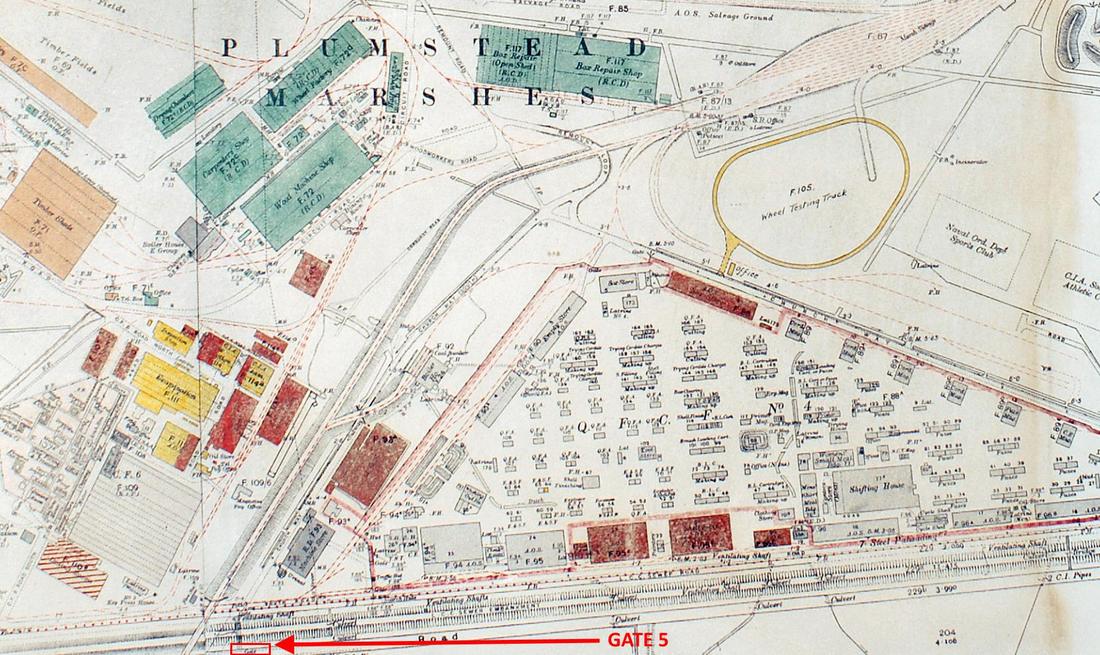

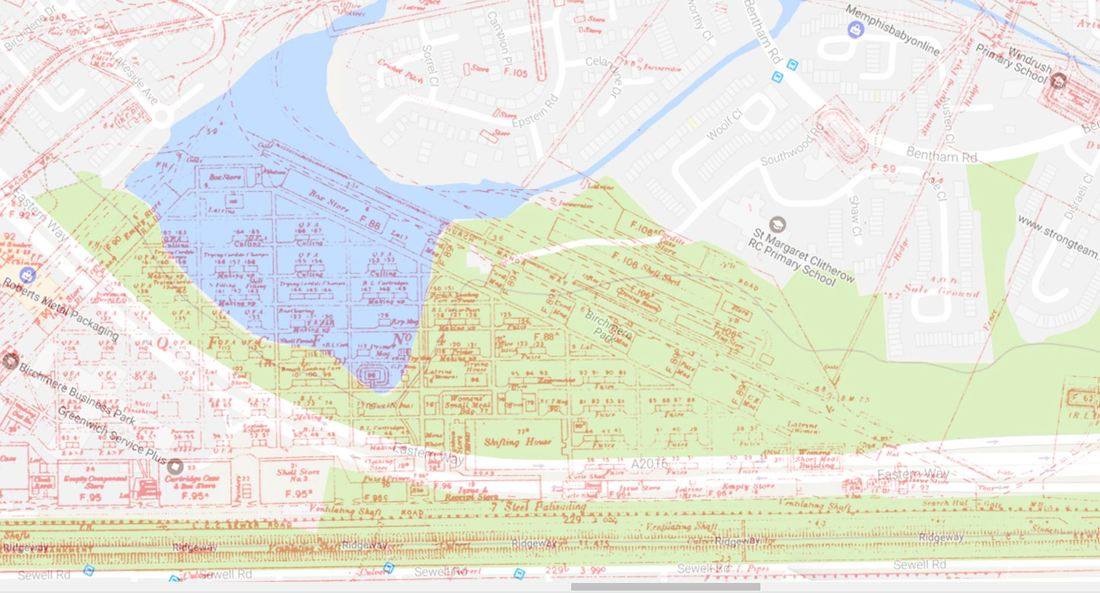

Cartridge Factory (Cannon) Danger buildings area with wooden platforms located somewhere in Thamesmead area today right of canal, swing bridge

A group of female munition workers employed at Woolwich Arsenal to manufacture detonator plugs dated 1914-18

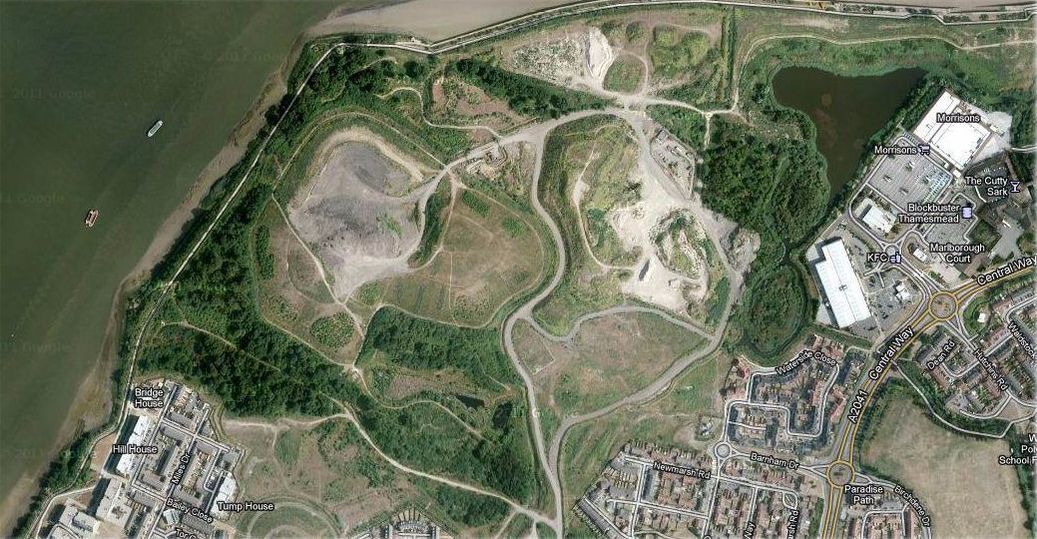

Danger Building Location (Today Thamesmead)

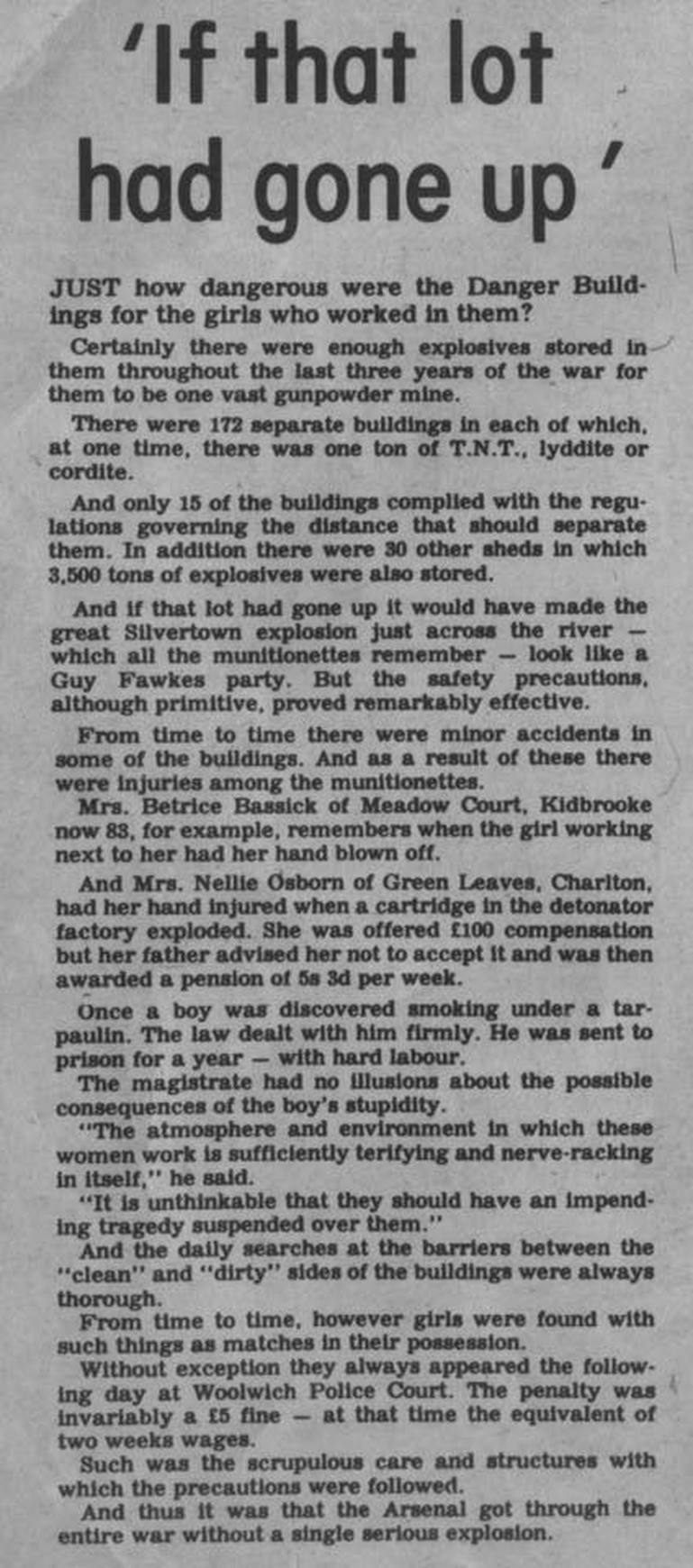

DBS - Royal Arsenal worker records

The records relating to the munitions factory workers were retained beyond the normal retention period of 100 years from date of birth. The record set is not complete as some records were destroyed during bombing and other accidents that occurred at the Factories, but they have approximately 170,000 record sheets of staff employed at the various Royal Ordnance Factories, including the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich. All available records are currently held by DBS in their archives.

Only a basic record sheet is held, but family members, or those carrying out genealogical research, do find the limited information to be of interest.

For all enquiries that they are able to assist in their contact details are:

Email: [email protected] quoting 'Information & Records Management request'

Tel: 0800 345 7047 (STD)

+44 1225 747750 (Overseas)

The earliest date of birth that they have noticed is 1862 and the records tend to be service records from the late 1920s-1930s onwards to the 1980s (prior to the ROFs being privatised). The majority of record sheets they hold cover the period of employment between 1930-1950. The pre-1929 records are stored in strict Alphabetical order so it only takes a few minutes to look up a record sheet if you have the full name and also date of birth (approximate year is a help). The post-1929 records are stored by year of birth and then alphabetical so they would need the year of birth to locate the individual's record sheet.

Also the greenwich heritage centre now has a data base of munitionettes names, addresses and other information ..... all collected in 2016

Only a basic record sheet is held, but family members, or those carrying out genealogical research, do find the limited information to be of interest.

For all enquiries that they are able to assist in their contact details are:

Email: [email protected] quoting 'Information & Records Management request'

Tel: 0800 345 7047 (STD)

+44 1225 747750 (Overseas)

The earliest date of birth that they have noticed is 1862 and the records tend to be service records from the late 1920s-1930s onwards to the 1980s (prior to the ROFs being privatised). The majority of record sheets they hold cover the period of employment between 1930-1950. The pre-1929 records are stored in strict Alphabetical order so it only takes a few minutes to look up a record sheet if you have the full name and also date of birth (approximate year is a help). The post-1929 records are stored by year of birth and then alphabetical so they would need the year of birth to locate the individual's record sheet.

Also the greenwich heritage centre now has a data base of munitionettes names, addresses and other information ..... all collected in 2016

Last Surviving Danger Building Area

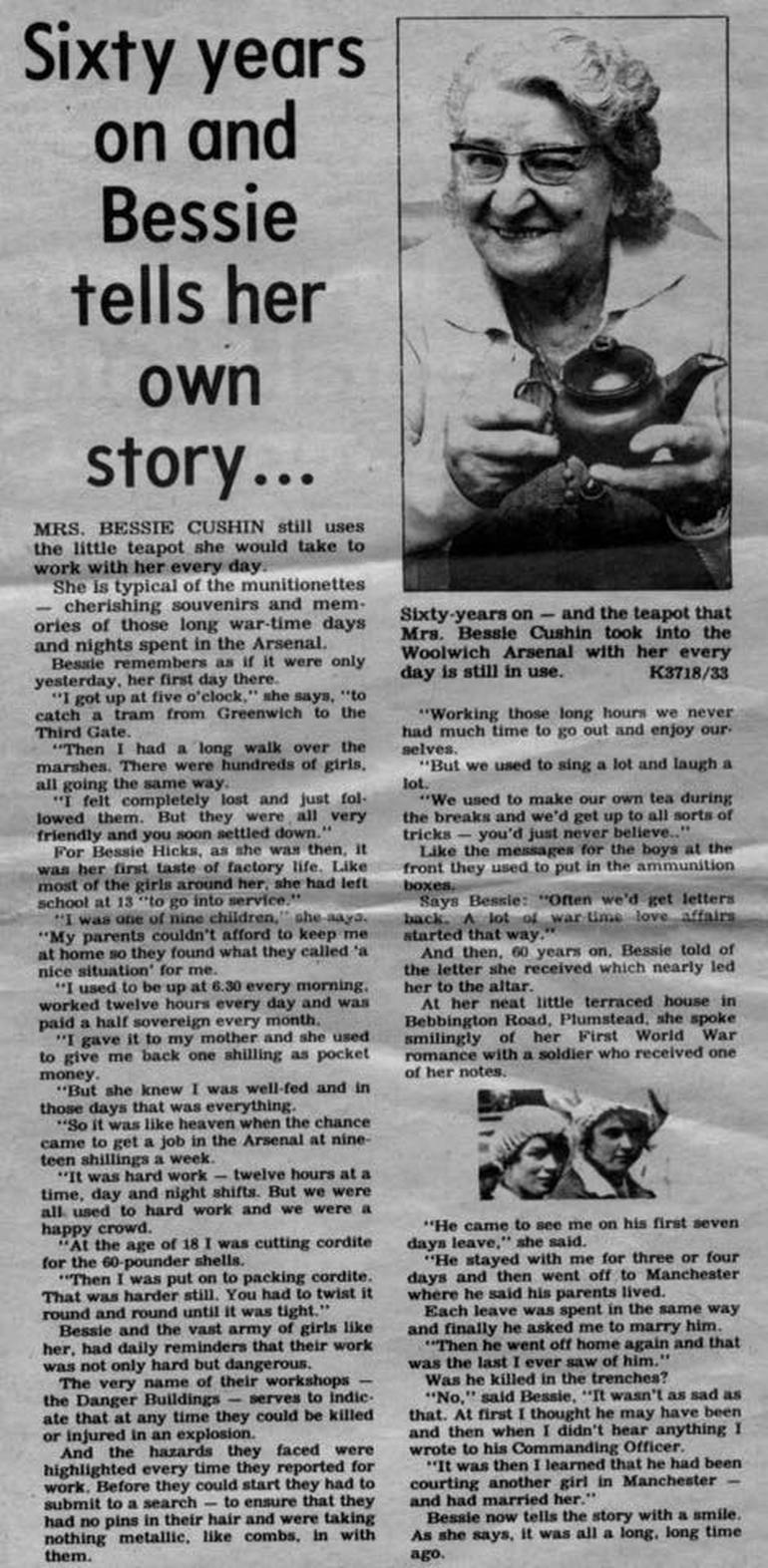

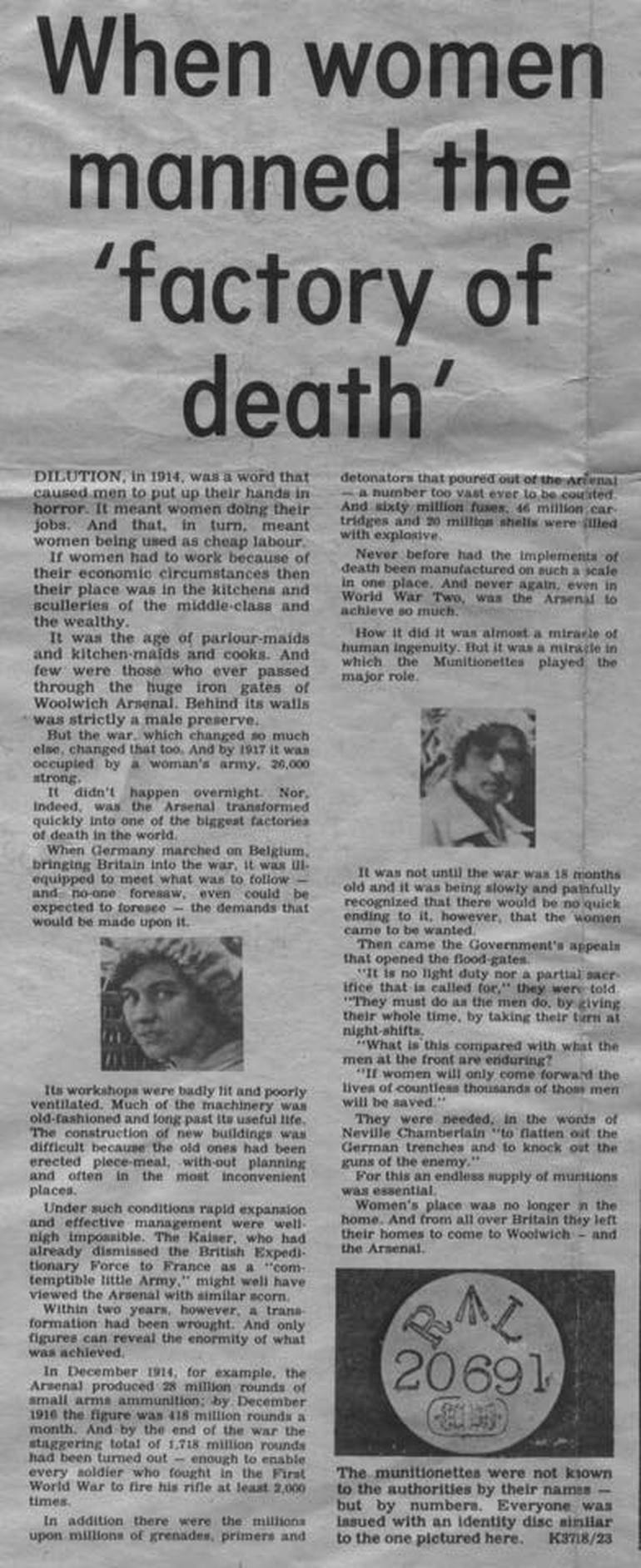

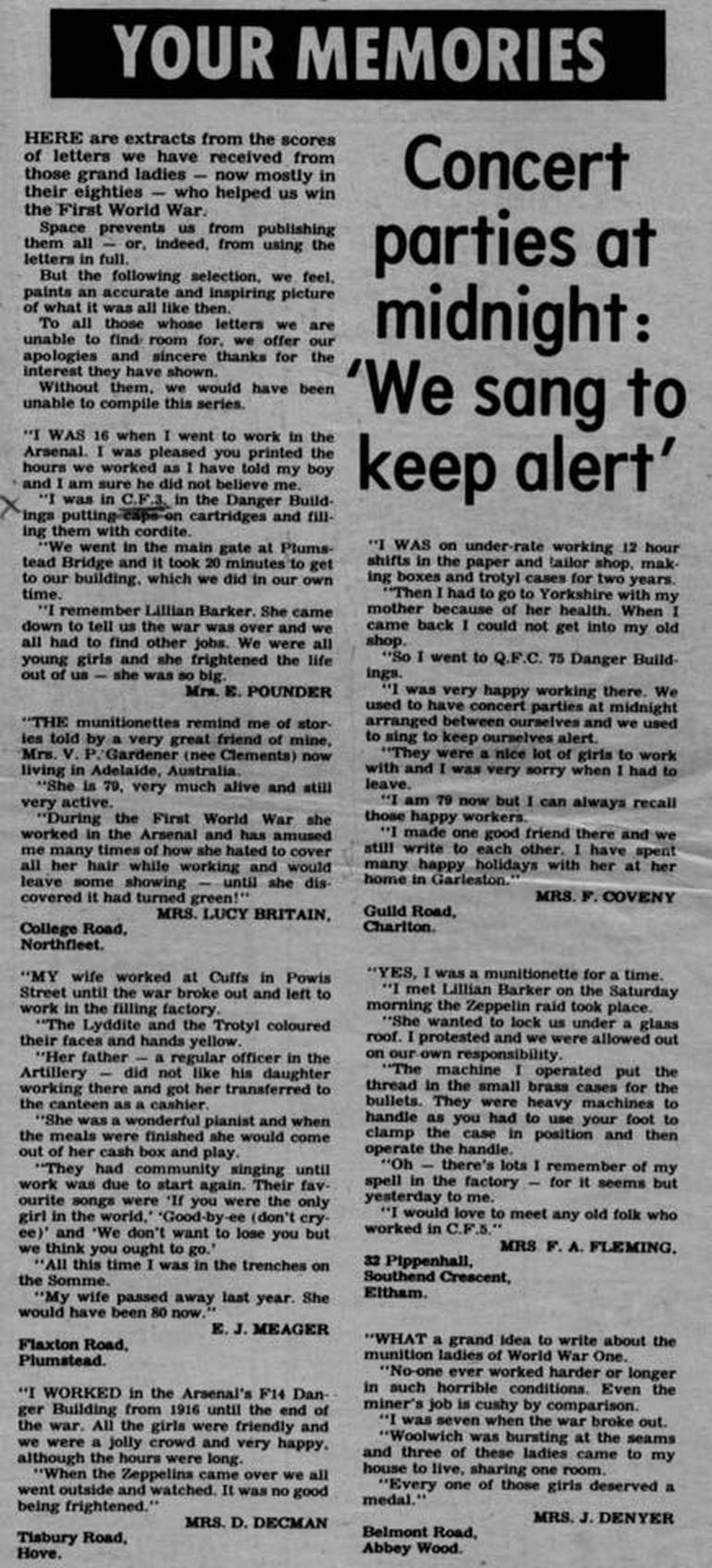

Women Worker newspaper clippings

More information here

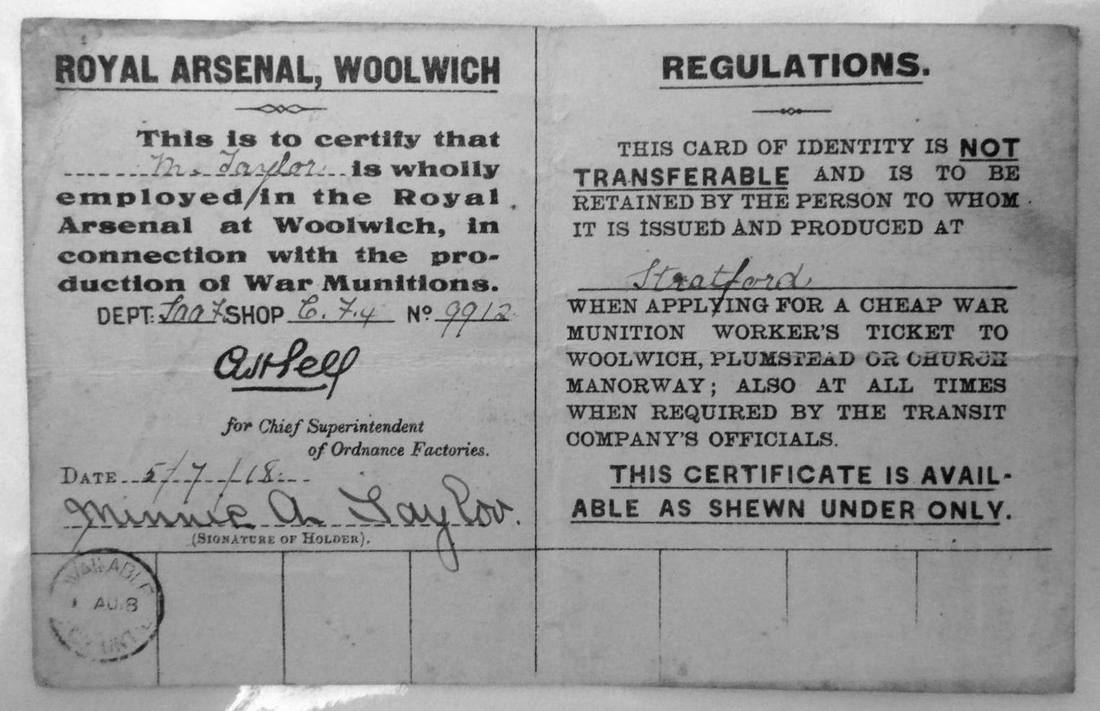

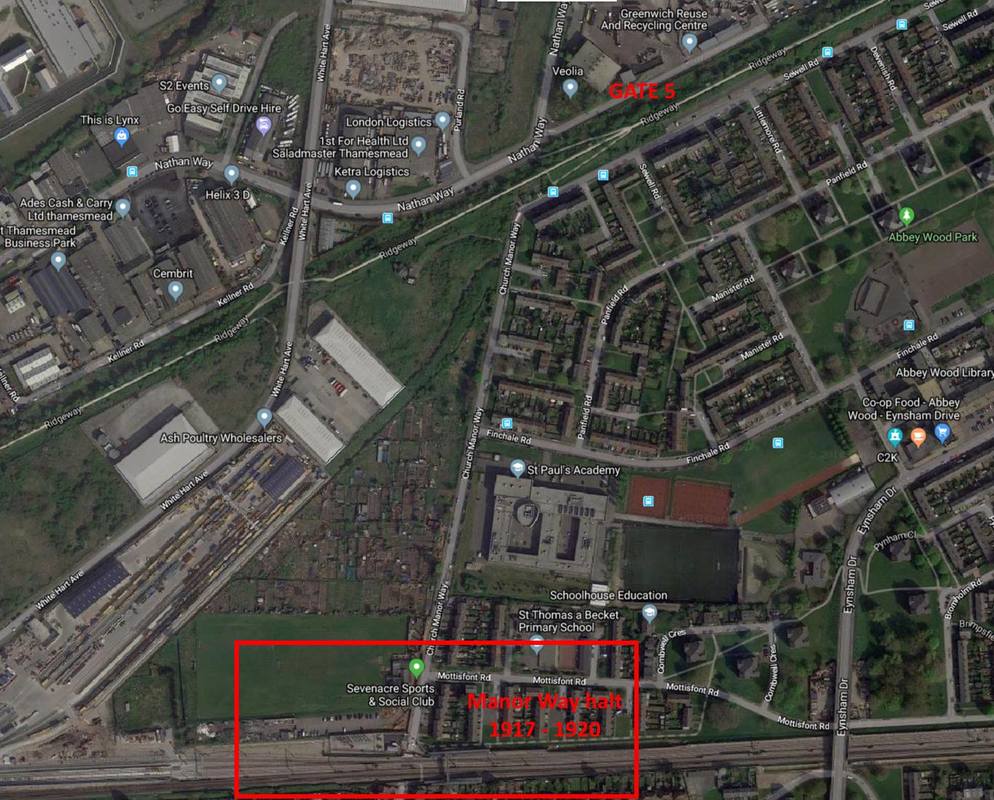

Manorway holt

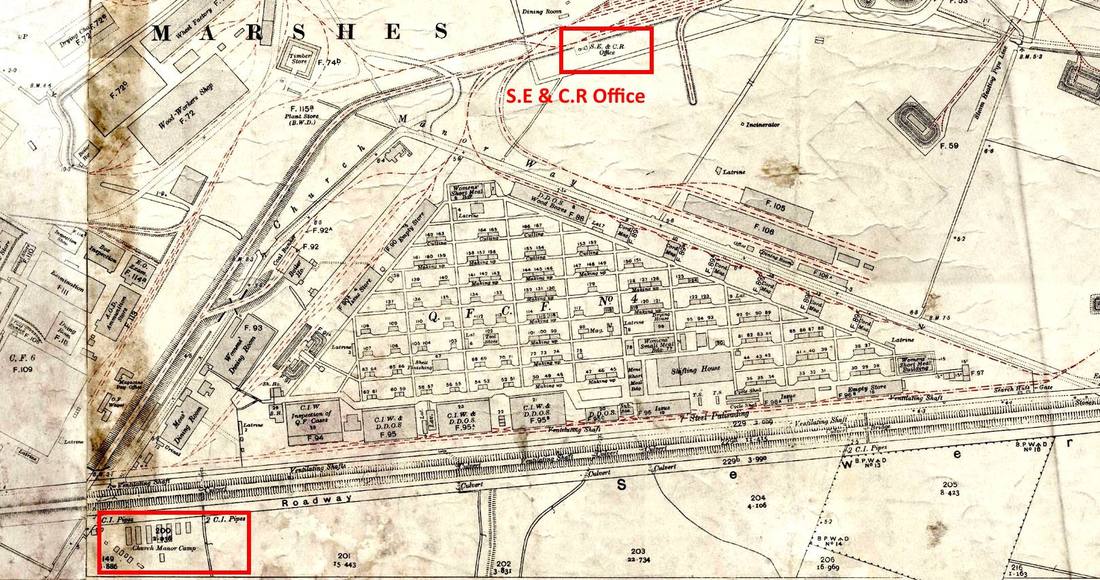

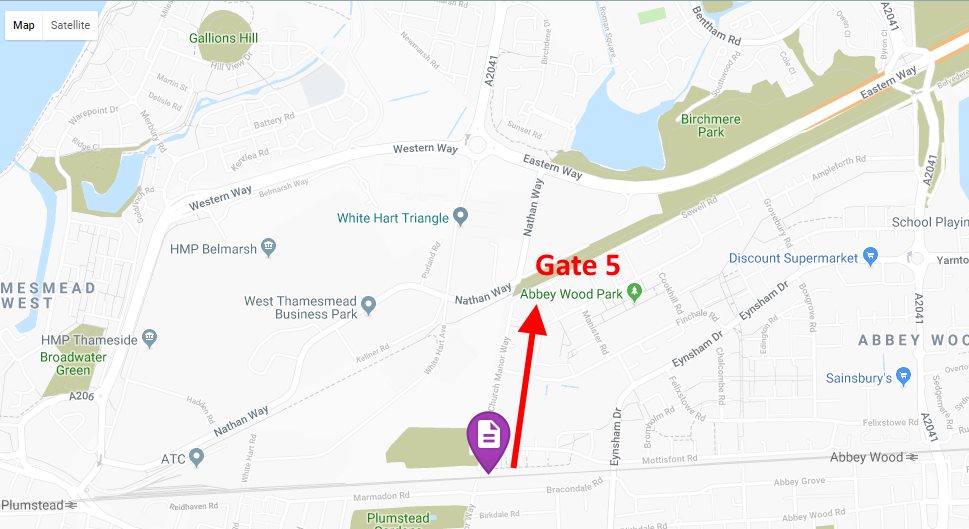

Church Manor Way halt. The closest Station to Thamesmead on the main line. It was opened in 1917 and closed in 1920.

The halt was named Church Manor Way after the road in which it was situated built to serve munitions workers at Woolwich Arsenal.

Attached pass issued to Royal Arsenal workers to allow them to get a cheaper fare and ticket with maps highlights to confirm the nearest location from piecing evidence together.

You will see that it covers three stops; Woolwich, Plumstead and Church Manorway (Just before Abbeywood station)

The SEE & CR (South Eastern and Chatham Railway) had passenger stations at Plumstead and at Abbey Wood and placing a Halt at Church Manor Way was practical.

When looking at the maps I have added you will see that there was already an Arsenal pedestrian gate at Church Manor Way, a gate that was close by the Sewer Bank and the SE & CR line. It therefore made sense to build a Halt at that point. The Quick Firing Cartridge Factory's (QFCF4) was situated in Birchmere park area. If you have any more information please add to this post.

The halt was named Church Manor Way after the road in which it was situated built to serve munitions workers at Woolwich Arsenal.

Attached pass issued to Royal Arsenal workers to allow them to get a cheaper fare and ticket with maps highlights to confirm the nearest location from piecing evidence together.

You will see that it covers three stops; Woolwich, Plumstead and Church Manorway (Just before Abbeywood station)

The SEE & CR (South Eastern and Chatham Railway) had passenger stations at Plumstead and at Abbey Wood and placing a Halt at Church Manor Way was practical.

When looking at the maps I have added you will see that there was already an Arsenal pedestrian gate at Church Manor Way, a gate that was close by the Sewer Bank and the SE & CR line. It therefore made sense to build a Halt at that point. The Quick Firing Cartridge Factory's (QFCF4) was situated in Birchmere park area. If you have any more information please add to this post.